Michael

J. Fleming, Deborah Leonard, Grant Long, and Julie Remache

The

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has actively used changes in the size and

composition of the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio to implement monetary

policy in recent years. These actions have been intended to promote the Committee’s

mandate to foster maximum employment and price stability but, as discussed in a

prior post, have also generated high levels of portfolio

income, contributing in turn to elevated remittances to the U.S. Treasury. In

the future, as the accommodative stance of monetary policy is eventually

normalized, net portfolio income is likely to decline from these high levels

and may dip below pre-crisis averages for a time, potentially contributing to a

suspension in remittances (Carpenter

et al. 2013). But what would the path of the

portfolio and income look like had these unconventional balance sheet actions not

been taken? In this post, we conduct a counterfactual exercise to explore such

a scenario.

Our counterfactual scenario assumes

that the Fed responded to the financial crisis only by lowering the federal funds

target rate. That is, no unconventional changes were made to the size or

composition of the portfolio, and no credit or liquidity facilities were set up.

As such, from August 2007, the counterfactual SOMA portfolio remains an

all-Treasury portfolio that grows roughly in line with currency in circulation.

We compare this to the “baseline” scenario from the New York Fed’s report Domestic Open Market Operations during 2012,

which reflects actual balance sheet developments through December 31, 2012, and

a projected portfolio path, based on primary dealer expectations from the

Desk’s Survey of Primary Dealers and the exit strategy principles articulated

in the June 2011 FOMC minutes (including mortgage-backed-security sales), after

that. Other Fed balance sheet items follow trend growth, consistent with the

projection methodology detailed in Carpenter

et al. 2013.

An important and artificial

simplifying assumption is that interest rates follow the same path for the

baseline and counterfactual scenarios. That is, under both scenarios, we apply

actual market interest rates through the end of 2012 and assume a future path

of short- and long-term interest rates after that, drawn from publicly

available surveys. In fact, long-term interest rates may have been higher or

lower in the absence of unconventional monetary policy. For example, it’s

plausible that the Fed would have maintained the same exceptionally low

short-term interest rates through the crisis and its aftermath, but that the

absence of the Fed’s large-scale asset purchases would have resulted in higher

long-term interest rates. Alternatively, economic and financial conditions

might have recovered even more slowly in the absence of unconventional policy,

contributing to a lower path for long-term rates. Given the difficulty of

estimating what rates would have been under the counterfactual, we make the simplifying

albeit fictitious assumption that rates would have been the same.

SOMA Securities Holdings

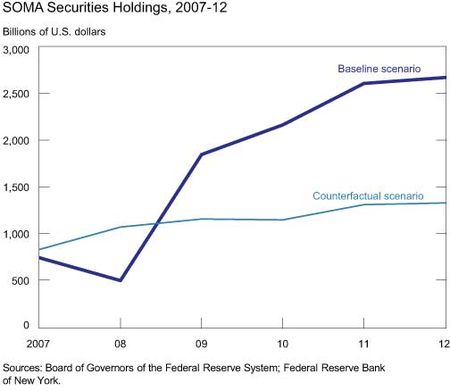

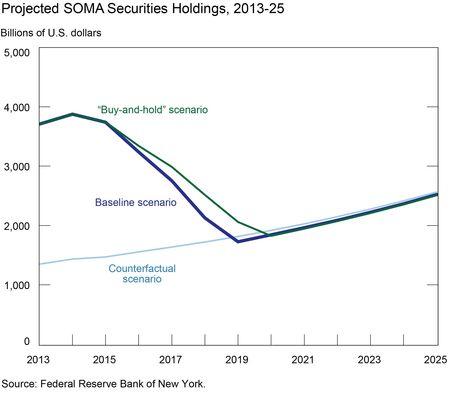

Under the counterfactual scenario, SOMA domestic securities holdings—consisting

entirely of Treasury securities—were $1.3 trillion as of year-end 2012, or roughly

$1.4 trillion lower than the baseline’s $2.7

trillion portfolio,

composed of Treasuries, agency debt, and agency mortgage-backed securities (see

chart below). The Treasury holdings of the counterfactual portfolio, which

maintains the pre-crisis allocation of one-third in Treasury bills, had a weighted

average maturity (WAM) of 5.4 years as of year-end 2012, similar to the WAM of

the outstanding supply of Treasury securities, but significantly shorter than the

WAM of 10.4 years of the baseline portfolio’s Treasury holdings.

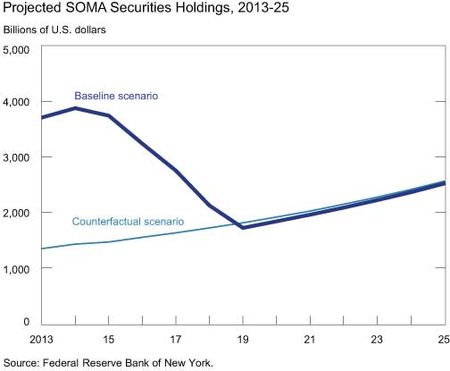

Going forward, we project the counterfactual

portfolio to continue to grow steadily, in line with currency growth, through

the end of our forecast horizon in 2025. In contrast, the baseline portfolio is

projected to follow a more varied contour, rising to a peak of nearly $3.9

trillion in early 2014 following the completion of the asset purchases assumed in

this scenario. Portfolio balances remain elevated through early 2015 before

declining steadily through a combination of redemptions and asset sales during

the policy normalization period (drawn from the FOMC’s June 2011 exit strategy principles).

The sizes of the two portfolios roughly converge in 2019. Although the baseline

portfolio returns to a nearly all-Treasury composition in 2021, the composition

of its securities holdings still has a slightly higher WAM than the counterfactual

portfolio because of the longer-term Treasury securities that were purchased in

recent years.

Portfolio Income

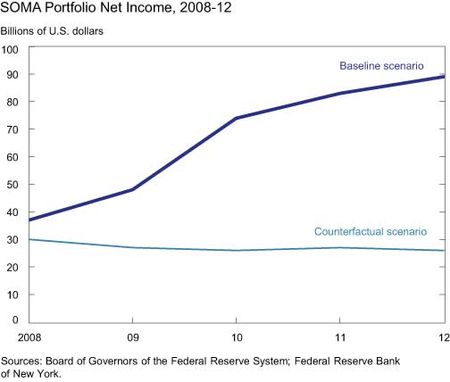

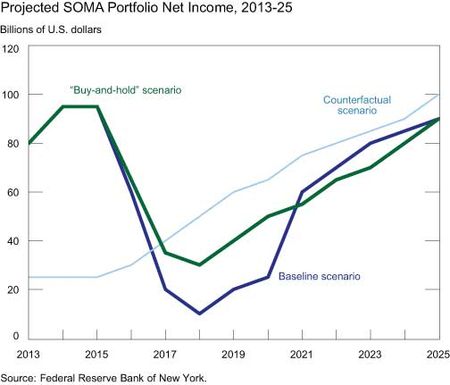

What about the income generated by the SOMA portfolio? We estimate relatively

steady net income under the counterfactual scenario, averaging approximately $27

billion annually from 2008 to 2012 (see chart below). In actuality, as seen in

the baseline, the FOMC’s efforts to provide additional accommodation through

use of the SOMA portfolio contributed to rising levels of net portfolio income over

this period, peaking at almost $90 billion in 2012. The lower level of income

during the crisis under the counterfactual scenario reflects the shorter

maturity structure and smaller size of the counterfactual portfolio.

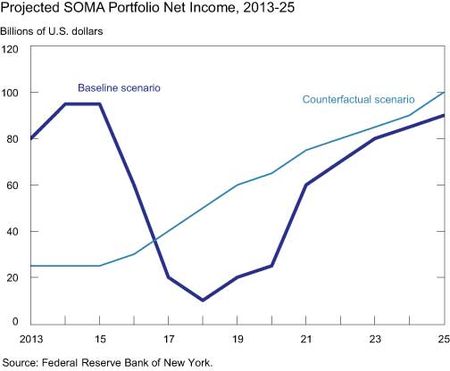

However, the baseline portfolio is not expected to continue generating such high income as the stance of monetary

policy is eventually normalized. Under the assumptions in the baseline

scenario, portfolio net income is projected to fall beginning in 2016 and to

remain low for several years. This reflects the interplay of several factors,

including higher interest payments on excess reserve balances as interest rates

rise, declining interest income as the size of the portfolio returns to lower

levels, and realized capital losses as agency mortgage-backed securities are

sold.

In contrast, portfolio income

associated with the counterfactual SOMA portfolio is projected to grow (from

dampened levels) as policy normalization takes place. Because this portfolio is

heavily invested in shorter-term Treasury securities, it sees interest income increase

as the portfolio rolls over in an environment of rising interest rates. Moreover,

because the portfolio is funded primarily with currency, it has only minimal

interest expense associated with reserves. Income associated with both

portfolios is expected to converge roughly to the same path late in our

projection period. By then, the baseline scenario returns to a “steady state”

in which its holdings are predominantly Treasury securities and its size once

again roughly matches currency.

Remittances to the Treasury

Fed income—after covering operating costs, dividends, and capital

maintenance—is remitted to the Treasury. The high levels of income that have

been generated by the SOMA portfolio, as well as non-SOMA sources of income

from the various credit and liquidity programs established during the crisis,

have contributed to elevated remittances to the Treasury since the crisis. At

$325 billion, cumulative remittances from year-end 2007 through year-end 2012

are roughly $240 billion higher than the estimated $85 billion of cumulative

remittances under the counterfactual scenario. This difference arises despite higher

interest costs incurred from funding the larger securities portfolio with

excess reserves.

Going forward, should the Fed not

generate sufficient income to cover its operating costs, dividends, and

transfers to capital, it would book a deferred asset (reported for

presentational convenience as a negative liability on the H.4.1 statistical release)

and temporarily halt remittances to Treasury. The deferred asset represents the

value of earnings that would have to be accrued over time to cover that shortfall, and it would have to be paid down before remittances could resume. Declines in net portfolio

income in our baseline scenario suggest the possibility of a deferred asset and

halt in remittances for several years. With a steadier projected path for the

portfolio and income, the counterfactual scenario would avoid that outcome.

Nonetheless, the

baseline portfolio is projected to remit a cumulative total of $820 billion to the Treasury

from 2008 through 2025, or $315 billion more than in the counterfactual

scenario. This arises from its higher overall income, even if the timing of how

it is remitted over the course of the period is less smooth than in the

counterfactual.

Our estimates of Fed income and

remittances under the counterfactual are necessarily rough as they depend on

various assumptions mentioned earlier, including the unrealistic assumption

that interest rates would have been the same in the counterfactual. In

practice, rates would likely have been considerably different if the FOMC had

not responded as forcefully as it did in recent years. Moreover, when

considering the net effects of monetary policy on the government’s fiscal

position, one should also account for the lower borrowing costs and support for

the economic recovery the Fed’s actions have produced, a point addressed in tomorrow’s

post. Nonetheless, our findings broadly highlight the wide margin by which unconventional

monetary policy has boosted cumulative remittances to the Treasury in recent

years.

Addendum

(August 23, 2013)

The above analysis presented the same baseline scenario as

shown in the New York Fed’s April 2013 report, Domestic

Open Market Operations during 2012. That scenario projected a portfolio

path based on roughly $1.1 trillion in asset purchases between 2013 and early

2014, drawn from the Desk’s December

2012 post-FOMC “Survey of Primary Dealers.” It followed the exit strategy

principles outlined in the FOMC’s June 2011 minutes, including the anticipated

sale of agency MBS assets during policy normalization, which was the most

current guidance on the topic at the time of the report’s drafting. Since then,

the minutes of the June 2013 FOMC meeting noted that most FOMC participants now

anticipate that the Federal Reserve would not sell agency MBS as part of the

process of normalizing the size of the balance sheet, although some

participants indicated that limited sales might be warranted in the longer run

to reduce or eliminate residual holdings. The annual report also considered an

alternative “buy-and-hold” scenario that illustrates how the baseline balance

sheet and income projections change in the case of no asset sales.

As shown in the charts below, the differences in portfolio and income effects

associated with specific choices regarding MBS assets during the normalization

process are relatively small compared to the effects that either of these

scenarios have relative to the counterfactual and that have already been

realized since the initiation of LSAPs in late 2008. With no asset sales, ceteris paribus, the general contours of

the portfolio’s size and income are projected to follow similar overall paths

as the baseline. However, the buy-and-hold portfolio is expected to take

slightly longer to converge in size with the counterfactual portfolio, at which

time its size once again roughly matches currency levels. Importantly, its composition

includes significant holdings of both agency MBS and Treasury securities. A

buy-and-hold scenario avoids capital losses on agency MBS sales but has higher

interest expense from additional reserve balances associated with a larger

portfolio, on net resulting in higher portfolio net income over the medium term

compared to the baseline and leading to roughly $55 billion cumulatively in

additional remittances to the Treasury. These are, of course, merely

illustrative projections. Actual future income and remittances will be

influenced by the ultimate size of the purchase program, as well as other

balance sheet, interest rate, and economic developments.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Michael J. Fleming is a vice president

in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Deborah Leonard is an assistant vice president in the Markets Group.

Grant Long is an associate in the Markets Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

We have updated our post with the addendum above.