Rajashri Chakrabarti and John Grigsby

Higher education is pivotal in our society—yet, its landscape is changing. Over the past decade, the private, for-profit sector of higher education has seen unprecedented growth, and its market share is at an all-time high. While we know much about traditional four-year public and private non-profit institutions, the for-profit sector seems more opaque. What services does it provide? Who enrolls at for-profits, and how has their enrollment changed during the Great Recession? What are their tuition levels? How about their net prices and student loans? And do their students succeed? We shed some light on these important questions in today’s economic press briefing at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and in a new set of interactive maps and charts released today by the New York Fed.

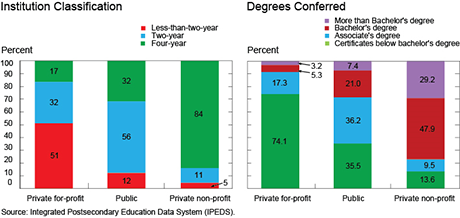

• Who are the for-profits? The charts below indicate that the vast majority of for-profit institutions concentrate on short programs (two years or less), and offer certificates below bachelor’s and associate’s degrees.

Thus, for-profits are more comparable to public community (two-year) colleges and public undergraduate certificate programs (less than two years) than to traditional four-year programs. Yet, while public community colleges and certificate programs often focus on academics or General Educational Development (GED) test preparation, for-profits are primarily trade schools, where enrollees can learn specific skills such as hairdressing, massage, welding, mechanics, or network and computer systems administration.• Enrollment at for-profits has skyrocketed, especially during the Great Recession: Between 2000 and 2011, for-profit enrollment in less-than-two-year institutions more than doubled, with 52 percent of this growth taking place in the three years after the onset of the Recession. During the same period, enrollment in public less-than-two-year institutions actually fell by 3 percent. The post-recession increase was in part fueled by increasing enrollment of students aged twenty-five or older, suggesting that for-profits might have been utilized by displaced workers looking to retool their skillset after a job loss, and by young adults looking to gain a tradable skillset.

• Tuition and student loans are much higher at for-profits than publics: Although for-profit student entrants have relatively lower incomes, tuition at for-profits has also been on the rise. In 2012, the average sticker price of a for-profit program was more than $14,300, up almost 100 percent from 2000. Despite availing themselves of higher Pell Grants, students at for-profits pay considerably higher net prices than those at public colleges, partly due to the absence of state and institutional grants. The high net price of for-profit programs has forced students to take out large loans to finance their education. In 2012, 60 percent of for-profit students not in four-year colleges took out subsidized student loans, at an average of $3,445 per loan; by contrast, just 15 percent of comparable public college students took out loans, with an average size of $3,096.

• What about student outcomes? Around 60 percent of students at for-profits complete their program within 150 percent of the normal time. But while graduation rates are respectable, graduates of for-profits are more likely to earn less, default more, and experience unemployment more than their counterparts at public and non-profit institutions.

While student outcomes at for-profits have not been too rosy, and the gap in student loans with comparable publics has been a persistent source of concern and debate, it is too early to pass judgment on the sector. Their remarkable enrollment growth during the Great Recession suggests that for-profits have allowed laid-off workers to train in new skills, and young adults to receive a college degree, which they may not have otherwise accomplished. As the economy evolves and recovery takes hold, it remains to be seen how the increase in enrollment will affect human capital formation and, by extension, our economy. Stay tuned for future posts exploring this increasingly important part of the higher education landscape.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I often wonder what would happen if instead of criticizing each other, we would stop to measure the benefit and consequences of our actions. We as educators pride ourselves in research and assessment. However, do we stop to think and then implement the results of our assessments? The tag price of any credential awarded is based on who is paying. At a public institution the cost of a credential is primarily sustained by the Tax Payers funding without any constrains. At a private for profit the cost of a credential is sustained by available loans funded by Tax Payers through funds that need to be paid back. What would happen if both forms of incorporation, public or private for profit, were functioning under the same scenario, awarding credentials governed by the same Fiscal Policies? What would the results then show? The metrics of retention, graduation and placement will then be measured under equal circumstances and accomplishments of objectives will then tell the true story of the performance of private for profit institutions. Hence, we could see the Department of Education endorsing private for profit institutions rather than battling them once the results of those scenarios are weighted under the same circumstances and their accomplishments are truly reflected on the results of the metrics. After all what are charter schools? City College of San Francisco is a good example, lack of funding will cease the operation of an institution whether public or private.

s Has a former VP for marketing and admissions at a large global proprietary for profit company it is not so much the programs themselves but rather the recruiting and hard sell of these schools that is truly sad. They know which demographics to hit hardest, how to manipulate the financial aid programs and enroll students who they know will default no matter what. I was held accountable for admission numbers that were insane on all fronts, yet everything was tied to meeting those numbers. While our culinary program, tied to Le Cordon Bleu in name only was decent, it was not meant or designed for everyone who thinks they can cook. We coerced people to move across country, to a place they never have been, with no housing or money and pretended that we were saving them from no future whatsoever. The outright manipulation of federal funds, twisting of arms to obtain one or more cosigners and the pressure put on the students was intense. Nothing compare on the public or private non profit side. The sheer greed of the companies and Wall Street is what drove insane growth not the demand by students or the actually need for this kind of training in the market place. The top Cs made millions in 4 to 5 years and left in a hurry. Not one that was at the elm of the top 4 companies in 2008 are there now. It says it all, turnover in this industry at all levels is enormous. The best and the worst four years of my professional life.