James Narron and David Skeie

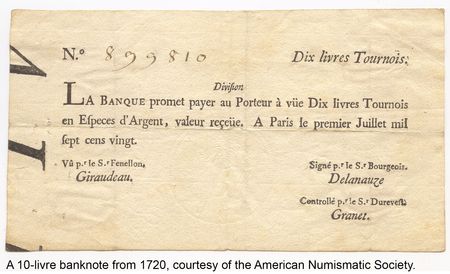

Convicted murderer and millionaire gambler John Law spotted an opportunity to leverage paper money and credit to finance trade. He first proposed the concept in Scotland in 1705, where it was rejected. But by 1716, Law had found a new audience for his ideas in France, where he proposed to the Duke of Orleans his plan to establish a state bank, at his own expense, that would issue paper money redeemable at face value in gold and silver. At the time, Law’s Banque Generale was one of only six such banks to have issued paper money, joining Sweden, England, Holland, Venice, and Genoa. Things didn’t turn out exactly as Law had hoped, and in this edition of Crisis Chronicles we meet the South Sea’s lesser-known cousin, the Mississippi Bubble.

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

John Law was an interesting figure with a colorful past. He was convicted of murder in London but, with the help of friends, escaped to the continent, where he became a millionaire through his skill at gambling. Like South Sea Company Director John Blunt in England, Law believed that a trading company could be leveraged to exchange the monopoly rights of trade for the ability to make low-interest-rate loans to the government. And like Blunt, in 1719 Law formed a trading company—the Mississippi Company—to exploit trade in the Louisiana territory. But unlike Blunt or the South Sea Company, the Mississippi Company made an earnest effort to grow trade with the Louisiana territory.

In 1719, the French government allowed Law to issue 50,000 new shares in the Mississippi Company at 500 livres with just 75 livres down and the rest due in nineteen additional monthly payments of 25 livres each. The share price rose to 1,000 livres before the second installment was even due, and ordinary citizens flocked to Paris to participate. Based on this success, Law offered to pay off the national debt of 1.5 billion livres by issuing an additional 300,000 shares at 500 livres paid in ten monthly installments.

Law also purchased the right to collect taxes for 52 million livres and sought to replace various taxes with a single tax. The tax scheme was a boon to efficiency, and the price of some products fell by a third. The stock price increases and the tax efficiency gains spurred foreigners to Paris to buy stock in the Mississippi Company.

By mid-1719, the Mississippi Company had issued more than 600,000 shares and the par value of the company stood at 300 million livres. That summer, the share price skyrocketed from 1,000 to 5,000 livres and it continued to rise through year-end, ultimately reaching dizzying heights of 15,000 livres per share. The word millionaire was first used, and in January 1720 Law was appointed Controller General.

The Trickle Becomes a Flood

Reminiscent of a handful of florists failing to reinvest in tulip bulbs as we described in a previous post on Tulip Mania, in early 1720 some depositors at Banque Generale began to exchange Mississippi Company shares for gold coin. In response, Law passed edicts in early 1720 to limit the use of coin. Around the same time, to help support the Mississippi Company share price, Law agreed to buy back Mississippi Company stock with banknotes at a premium to market price and, to his surprise, more shareholders than anticipated queued up to do so—a surprise we’ll see repeated at the apex of the Panic of 1907. To support the stock redemptions, Law needed to print more money and broke the link to gold, which quickly led to hyperinflation, as we saw in our post on the Kipper und Wipperzeit.

The spillover to the economy was immediate and most notable in food prices. By May 21, Law was forced to deflate the value of banknotes and cut the stock price. As the public rushed to convert banknotes to coin, Law was forced to close Banque Generale for ten days, then limit the transaction size once the bank reopened. But the queues grew longer, the Mississippi Company stock price continued to fall, and food prices soared by as much as 60 percent.

To make matters worse, there was an outbreak of the plague in September 1720, which further restricted economic activity—in particular, trade with the rest of Europe. By the end of 1720, Law was dismissed as Controller General and he ultimately fled France.

Balancing Dispersed Debt Issuance against Central Monetary Policy

One might argue that Law suffered a self-inflicted loss of control over monetary policy once the link between paper money issuance and the underlying value of gold holdings was broken—a lesson that monetary authorities have learned over time. But what if you don’t have direct sovereign authority over banknote issuance or, in more modern times, monetary policy? A challenge that’s perhaps most visible in the Eurozone is how best to balance dispersed, country-specific debt issuance against more centralized authority over monetary policy. In an upcoming post on the Continental Currency Crisis, we’ll see why a united fiscal policy was needed along with the united currency and monetary policies. Could the same be true of Europe? And if so, would a united fiscal policy include Eurozone debt as well as centralized fiscal transfers, or perhaps even collection of taxes? Tell us what you think.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Narron is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Executive Office.

David Skeie is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

The initial premise of the schemes – leveraging a monopoly right on trade for the ability to make low interest loans to governments – appears to have been used again by the Swedish Match King, Ivar Krueger, during the 1920s. That didn’t end well either.

So much for privatization. The old private monopoly for public debt payment scam never works out well for the private sector or for the government, though it is invariably the government that is left to fill in the hole. It makes much more sense for the government to issue the currency and manage its own debt, ideally in its own currency. The US Treasury should just open a retail window to bypass Wall Street and then it wouldn’t have to provide trillion dollar credit lines to the incompetents in the private sector very decade or so.

Uhm, maybe we should stop worrying about finding ways to leverage debt (aka future growth – pulled into today – see Mississippi share sales) into prosperity because the lesson to be taken from this historical example is that it is a fool’s errand doomed to failure to begin with. No amount of monetary and or fiscal policy manipulation can ever overcome the shortfalls of private bank issued debt money. Which is exactly what the Federal Reserve Note and it’s fractional reserve credit money banking system is. Money must be backed by something more than the promise of the issuing bank to always print more …. and more … and more …. and more. Europe’s problems will only expand with fiscal unity, because you can not build a nation of one people, one economy and thus one tax system from the top down. You can not force these types of social changes on people over short time frames. These kind of social integrations have to happen organically over several generations to have any hope of lasting more than a few decades. Another fool’s errand doomed to failure.

I believe you are taking artistic license in your interpretation of the facts. The shares issued in the Mississippi Company in exchange for the debt was trading an asset of little value for another asset of little value. Law was never able to develop the business of the Mississippi company and the value of the shares would be never be able to make the bond owners whole. Law was ahead of his time and central banks have more market power to influence asset values in equity and bonds. The difference is that the you make the point that a united fiscal policy in Europe is needed today as was the case back in Law’s time. I beg to differ as a united policy in Europe is based on getting Germany to agree since they play the only card that matters. In Law case is was just a scheme that never had a long term chance to succeed unless the Mississippi company was successful.

I think that united fiscal policy Europe was needed along with the united currency and monetary policies…