Allan M. Malz, Ernst Schaumburg, Roman Shimonov, and Andreas Strzodka

The rise in the ten-year Treasury rate last summer was perhaps the most dramatic since the 2003 bond market sell-off. This post explains how major changes in the composition of agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) ownership caused by the large-scale asset purchase programs (LSAPs) may have prevented a major convexity event triggered by MBS duration extension hedging. In fact, MBS hedging activity remained muted by historic standards and likely contributed only modestly to the rise in interest rates.

Extension Risk

Historically, the risk of sudden yield curve movements has greatly affected the market for MBS, which represent claims on a pool of underlying residential mortgages. The interest rate risk of MBS differs from the interest rate risk of Treasury securities because of the embedded prepayment option in conventional residential mortgages that allows homeowners to refinance their mortgages when it is economical to do so: When interest rates fall, homeowners tend to refinance their existing loans into new lower-rate mortgages, thereby increasing prepayments and depriving MBS investors of the higher coupon income. However, when rates rise, refinancing activity tends to decline and prepayments fall, thereby extending the period of time MBS investors receive below-market rate returns on their investment. This is commonly known as “extension risk” in MBS markets.

Duration and Convexity

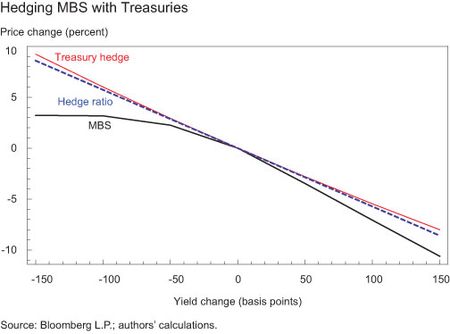

The effect of the prepayment option can be seen in the chart below, which displays the relationship between yield changes (x-axis) and changes in the value of an MBS (black) and a non-prepayable ten-year Treasury note (red). The sensitivity of each instrument to small changes in yields (essentially the slope of each yield-price relationship at the point at which the MBS was last hedged, indicated by the dashed line) is known as the effective duration, while the rate at which duration changes as yields change (the curvature of the price-yield relationship) is known as its convexity. In the example shown below, the MBS and Treasury security are duration matched in the sense that they will tend to move one-to-one for small changes in yields.

When interest rates increase, the price of an MBS tends to fall at an increasing rate and much faster than a comparable Treasury security due to duration extension, a feature known as the negative convexity of MBS. Managing the interest rate risk exposure of MBS relative to Treasury securities requires dynamic hedging to maintain a desired exposure of the position to movements in yields, as the duration of the MBS changes with changes in the yield curve. This practice is known as duration hedging. The amount and required frequency of hedging depends on the degree of convexity of the MBS, the volatility of rates, and investors’ objectives and risk tolerances.

Duration hedging of MBS can be done with interest rate swaps or Treasury bonds and notes. When rates decline, hedgers will seek to increase the duration of their positions. This can be achieved by buying Treasury notes or bonds, or by receiving fixed payments in an interest rate swap. Conversely, MBS holders will find the duration of their MBS extending when rates increase, which they may choose to offset by selling Treasury notes or bonds, or by paying fixed in swaps. If sufficiently strong, this hedging activity can itself cause interest rates to rise further, and further increase duration for MBS holders, inducing another round of selling of Treasuries.

A Convexity Event Averted

A sudden initial rise in medium- to long-term rates can therefore trigger a self-reinforcing sell-off in Treasury yields and related fixed income markets, fueled by MBS hedging—a phenomenon known as a convexity event. During a convexity event, MBS hedgers collectively attempt to decrease duration risk by selling Treasury securities or paying fixed in swaps. The two most important factors that determine the likelihood of a convexity event are the size of the MBS portfolio held by duration hedgers and the convexity of that portfolio. The large-scale purchases of MBS initiated by the Federal Reserve in November 2008 as part of the post-crisis LSAPs have had a profound impact on both these determinants.

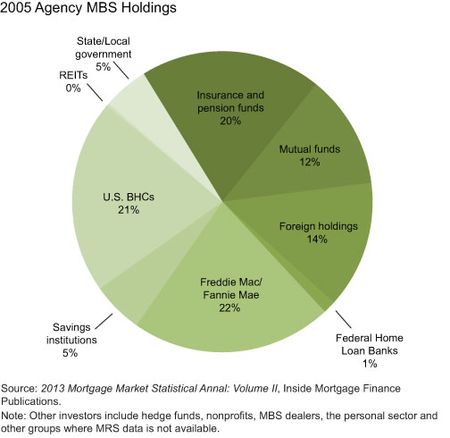

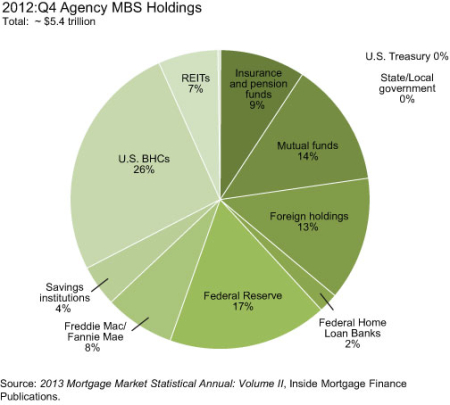

MBS investors, broadly speaking, fall into two categories: those holding MBS on an unhedged or infrequently hedged basis and those that actively hedge the interest rate risk exposure. Unhedged or infrequently hedged investors include the Federal Reserve, foreign sovereign wealth funds, banks, and mutual funds benchmarked against an MBS index. MBS holders who actively hedge include real estate investment trusts (REITs), mortgage servicers, and the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

The pie charts compare the holders of MBS in 2005 and at the end of 2012. The biggest change is the increase in Federal Reserve holdings, partly offset by a large reduction in the actively hedged GSE portfolio.

As can be seen in the earlier chart, the negative convexity of an MBS security (that is, the curvature of the black price-yield relationship) is greatest when the prepayment option is near- or at-the-money (or mortgage rates are close to the MBS coupon), but dissipates for sufficiently large rate changes. In May 2013, it was the 2010-13 MBS vintages that possessed the greatest levels of negative convexity. This is important because the Federal Reserve portfolio consists primarily of recently-issued low-coupon mortgages. Most of the holdings are in 3.5 percent or lower coupons, as the MBS purchased were primarily current coupon securities. While the Federal Reserve held slightly more than 20 percent of outstanding MBS by early summer 2013, it held a much larger fraction of the convexity risk of the MBS universe, a risk that was entirely borne by investors before the crisis.

The low-rate environment in early 2013 had arguably set the stage for a convexity event (historically low rates coupled with substantial negative convexity). As the ten-year yield rose from 1.70 percent in early May to 2.90 percent in August, mortgage portfolio durations extended significantly, forcing MBS hedgers to sell duration, or to sell the underlying MBS. However, by all accounts, the MBS-related hedging activity was more muted than in previous bond sell-off episodes, including those in 1994 and 2003. While the rate increase was similar in magnitude to the June 2003 sell-off, for example, it was

more gradual and therefore inconsistent with a sell-off driven primarily by convexity hedging. A convexity event of the intensity seen in 1994 and 2003 did not materialize in 2013, and the risk of one occurring in the near future is lower as the Fed continues to hold a significant portion of all mortgage convexity risk and mortgage rates have risen substantially from their early 2013 lows.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Allan M. Malz is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Ernst Schaumburg is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Roman Shimonov is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Andreas Strzodka is an associate in the Bank’s Markets Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

In other words, large scale government intervention in the market prevents the market from behaving as it would absent the intervention, is that correct?