Gara Afonso, João A.C. Santos, and James Traina

This post is the fourth in a series of thirteen Liberty Street Economics posts on Large and Complex Banks. For more on this topic, see this special issue of the Economic Policy Review.

In the previous post, João Santos showed that the largest banks benefit from a bigger discount in the bond market relative to the largest nonbank financial and nonfinancial issuers. Today’s post approaches a complementary Too-Big-to-Fail (TBTF) question—do banks take on more risk if they’re likely to receive government support? Historically, commentators have expressed concerns that TBTF status encourages banks to engage in risky behavior. However, empirical evidence to substantiate these concerns thus far has been sparse. Using new ratings from Fitch, we tackle this question by examining how changes in the perceived likelihood of government support affect bank lending policies.

A Measure of Government Support

Measuring government support is a challenge in itself. Some of the earlier work uses a measure commonly known as Moody’s “uplift,” which implicitly captures a bank’s external support by subtracting its stand-alone rating from its all-in credit rating. Other studies rely on Fitch’s Support Ratings. These measures, however, include not only the probability of government support but also support from the parent company. In our analysis, we use a new rating that Fitch started issuing in March 2007: the Support Rating Floors (SRFs). This rating uniquely isolates the likelihood of government support from other forms of support (such as from parent companies or institutional investors). In contrast to earlier measures, Fitch bases SRFs solely on its opinion of potential government support, that is, the will and ability of a government to support a bank.

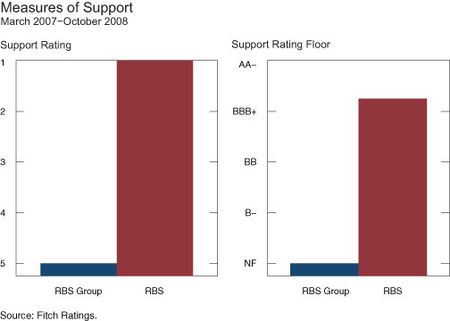

To get a sense of the importance of that difference, let’s consider the example of The Royal Bank of Scotland. RBS Group is the parent company of an international banking organization headquartered in Edinburgh (United Kingdom), and RBS is its largest banking subsidiary. As the chart below shows, from March 2007 to October 2008, RBS Group (the parent, in blue) had the lowest level of external support (support rating = 5), while RBS (the subsidiary, in red) enjoyed the highest level of external support (support rating = 1). By looking at support ratings only, we can’t say if the strong support of RBS comes from the government or from RBS Group (the parent company). However, RBS’s Support Rating Floor (SRF = A-) tells us that there’s strong perceived sovereign support.

Risk Response

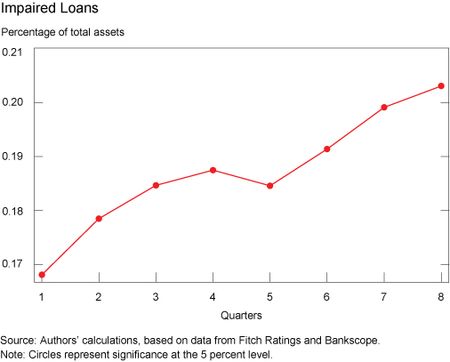

Do TBTF banks engage in riskier activities? Put differently, does higher government support translate into riskier loan portfolios? To address this question, we build a panel of bank-level data for 224 banks in 45 countries that includes Fitch ratings and balance-sheet information from March 2007 to August 2013. We measure the riskiness of a bank’s lending business by the ratio of impaired loans to total assets. Impaired loans are loans that are either in or close to default and are typically considered a good measure of the amount of bad debt in a bank’s loan portfolio. In our sample, the average bank has an impaired loan ratio of 2.48 percent of its total assets.

Because a bank’s response to government support might take time to show up on its balance sheet, we look at the effect on a bank’s impaired loans one to eight quarters after a change in its SRF. The analysis also includes controls to account for other factors that may explain deterioration in a bank’s loan portfolio. As shown in the chart below, stronger government support translates into a higher ratio of impaired loans. A one-notch rise in the SRF increases the impaired loan ratio by roughly 0.2—an 8 percent increase for the average bank. Importantly, this effect steadily increases through time and persists even eight quarters after a change in support.

We find similar results when we look at the effect of changes in government support on net charge-offs, a related measure of bad debt in bank loan portfolios. Moreover, this effect is still present when we zoom in on U.S. banks only. In our recent paper, we present robustness analysis that confirms these results. Our findings therefore lend support to the claim that “Too-Big-to-Fail” banks engage in riskier activities by taking advantage of the likelihood that they’ll receive government aid.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Gara Afonso is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

João A.C. Santos is a vice president in the Research and Statistics Group.

James Traina is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

This seems like an honest attempt by FRBNY to lay out the dynamics associated with financial-economic risk in light of several public policies that necessarily affect sifi’s. The solution lies in the separation of the societal economic effects from the financial system risks, and that is readily done by resort to some variation of a ‘public money’ scheme. There is no need to rely upon the private banking system, which is incapable of advancing the monetary and credit aggregates sufficient to achieve our economic potential…….which is what the Fed has the mandate to do. The only way for the Fed to have the tools needed to actually manage those aggregates is to nationalize the Federal Reserve into the Treasury system, and allow it to issue the nation’s money as needed to meet our socio-economic goals, as laid out in the Act. It’s time to end the borrowing by the government of monies that banks create out of nothing. In such circumstances, there would be no such thing as too big to fail or pay taxes.

Thirty years ago I taught finance on a postgraduate course for non-finance graduates in the City of London. I did a simple experiment to examine their attitude to risk. Two projects were available and they had to chose in which one to invest £100,000. (About eight or ten times their average salary). Project A has a 10% probability of making £1,000,000, 10% probability of losing all the money, both within the first year, and 80% probability of making 4% pa for 20 years. Project B has close to 100% probability of making 6% pa for 20 years, with no probability of losing the money. Scenario 1. You are owners of a firm so the profit or loss goes straight into or out of your pocket. One student chose project A. Scenario 2. You are managers of a firm, paid by salary plus commission based on a percentage of profit made and you would not lose money if you make a loss. In this scenario nearly a third of the students chose project A. If losses can directly affect an individual they are more risk averse. If investors believe that the State will bail out an institution when its projects fail, then they will accept and encourage the institution to take on high risk projects. Profitability is unlimited and there is a platform below which they cannot fall. Since the 1980’s unlimited liability has been replaced by limited liability and in some areas State guarantees, thus today institutions will take on more risk than prior to the 1980’s. It’s a natural consequence of our attitude to risk.

Isn’t there a correlation between bank size and charge-offs rates? Likewise, larger banks produce more non-interest revenue per client relationship, which could lead to greater competition in loan pricing.

Just curious if the rating agencies calculate same metric back to LTCM and S&L crises to see if the same result occur. Reason that would interesting as 2007/8 was systemic in nature hence a large number of bailouts were considered.

It seems to me that the government is more likely to bail out, or provide support to, a bank that has more troubled loans. In this case, you’d have the same correlation, but the causation runs the other way, no? It takes a long time for loan losses to flow through a book, so an 8-quarter increase in bad loans just shows that they had worse loan books to start with, not that they kept making bad loans based on expected government support. I’ll admit I haven’t read the full paper yet though. If there is something in there that addresses this, I’d be interested to see it. Thanks