Fernando M. Duarte and Thomas M. Eisenbach

This post is the third in a series of six Liberty Street Economics posts on liquidity issues.

Imagine that many large and levered banks suffer heavy losses and must quickly sell assets to reduce their leverage. We expect the market price of the assets sold to decline, at least temporarily. As a result, any other financial institutions that happen to hold the same assets will experience balance sheet losses through no fault of their own —a negative fire-sale externality. In this post, we show that the vulnerability to fire-sale externalities was high during the crisis and that the capital injections of the government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) helped reduce it considerably. In fact, we argue that given the total amount injected, TARP was close to optimal.

Fire sales are difficult to isolate and observe directly, especially in a crisis when multiple shocks concurrently afflict the financial system. But it is a bit less difficult to quantify the vulnerability of the financial sector to fire-sale externalities. To do so, consider the following hypothetical sequence of events, which captures the main aspects of any fire sale:

- Initial shock: Some or all financial assets decrease in value for whatever reason. To make our analysis simple, we assume that the initial shock decreases the value of all financial assets by 1 percent.

- Direct losses: Banks holding the affected assets suffer direct losses, an outcome that increases their leverage. For our analysis, we use public balance sheet information from banks’ regulatory filings to estimate the size of the direct losses given the initial shock.

- Asset sales: The empirical evidence indicates that in response to the increase in leverage, banks tend to sell assets and pay off debt so as to restore leverage to its original level (Adrian and Shin 2010a, 2010b, 2011). We also assume that banks sell their assets proportionately to their holdings.

- Price impact: The price impact of asset sales depends on each asset’s liquidity and how much of it was sold. We use the weights used in the proposed Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) to impute the liquidity of different asset classes.

- Spillover losses: Any financial institutions holding the fire-sold assets suffer spillover losses due to the price impact.

Although some of these assumptions are simplifications, the results are similar under various more realistic assumptions, as we show in our paper “Fire-Sale Spillovers and Systemic Risk.” (The paper also contains a more detailed explanation of the methodology and data used.)

The spillover losses in Step 5—as opposed to the direct losses in Step 2—are what policymakers should care about. The reason is that banks that suffer direct losses choose their portfolios without taking into account the losses they may cause to other financial institutions through their actions during a fire sale. To the extent that the spillover to other healthy financial institutions is detrimental to the economy as a whole, there is a role for government intervention. The situation is analogous to an industrial company polluting the environment: The pollution hurts everyone else, but because the polluting company does not bear the full social costs of the problem, it has insufficient incentive to stop.

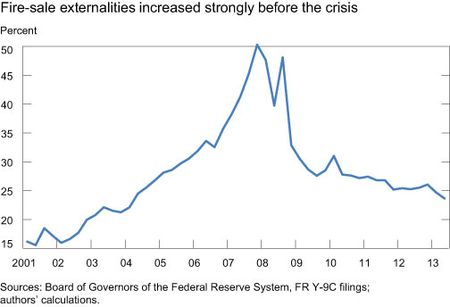

The next chart shows the spillover losses among the top 100 U.S. bank holding companies that would have occurred if the hypothetical scenario considered above had materialized in any quarter since 2001. We express the losses as a percentage of the aggregate amount of tier 1 capital. The first thing to notice is how large the fire-sale externalities can be. Even in normal times, a 1 percent decrease in the price of all assets can cause fire-sale externalities of about 20 percent of system equity. This number more than doubles during the crisis. The chart also shows that the vulnerability to fire sales in the system built up steadily after 2001 until the crisis. If policymakers had seen this measure before the crisis, it might have served as a good early warning indicator.

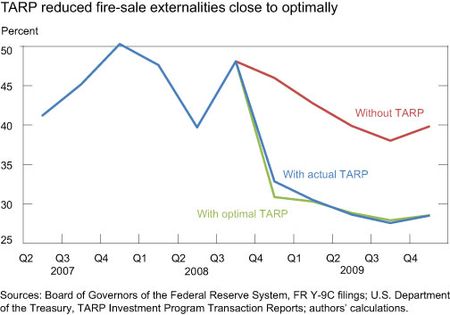

The next chart shows what the vulnerability to fire sales would have been under two alternative scenarios. In the first scenario, we model what would have happened if there had been no TARP capital injections. In the second scenario, we take the total amount of capital injected by TARP and distribute it optimally among banks so as to minimize vulnerability to fire-sale externalities. Comparing actual TARP to the first scenario of no TARP, we see that TARP decreased fire-sale vulnerabilities by about 12 percentage points of aggregate system tier 1 capital in each quarter after it was implemented in the fall of 2008. In dollar terms, the 12 percentage points correspond to about $100 billion. Since TARP capital injections for the institutions we consider totaled $212 billion, the reduction in fire-sale externalities produced a 1.5 “multiplier,” since capital increased by $212 billion and vulnerabilities decreased by an additional $100 billion.

Comparing actual TARP to the second scenario of optimal TARP, we see that TARP reduced fire-sale vulnerabilities close to the maximum possible extent given the size of the program. Actual TARP reduced the externality to 33 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008 while optimal TARP would have reduced it to 31 percent, a difference of only 2 percentage points. Our study suggests that in this particular dimension, TARP money was well used.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Fernando M. Duarte is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas M. Eisenbach is an economist in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

How do you price the cost of moral hazard in your models?