Meta Brown, Sydnee Caldwell, and Sarah Sutherland

Last year, our blog presented results from the FRBNY Consumer Credit Panel (CCP) indicating that, at a time of unprecedented growth in student debt, student borrowers were collectively retreating from housing and auto markets. In this post, we compare our 2012 findings to the news for 2013.

Between 2012 and 2013, U.S. auto and housing markets recovered substantially. The CoreLogic national house price index rose by 11 percent from December 2012 to December 2013. According to the Los Angeles Times, “It was the [auto] industry’s best year since 2007.” Last summer, this blog post discussed the sources of the ongoing auto recovery. Here we pose two questions: What part have young borrowers, with and without student debt, played in the recent housing and auto market recoveries? And, have the housing and auto purchases of young student borrowers at last accelerated past those of nonstudent borrowers, to once again reflect their skill and earnings advantages?

The share of twenty-five-year-olds with student debt continued to increase in 2013, as the group’s average student loan balance reached $20,926. For those twenty-five-year-olds with student loans, student debt now comprises 69 percent of the debt side of their balance sheets. Given the increased popularity of student loans, some have questioned how taking on extensive debt early in life has affected young workers’ post-schooling economic activity.

As in last year’s blog post, we address the association between student debt and subsequent economic activity by examining trends in homeownership, auto debt, and total borrowing at standard ages of entry into the housing and vehicle markets for U.S. workers.

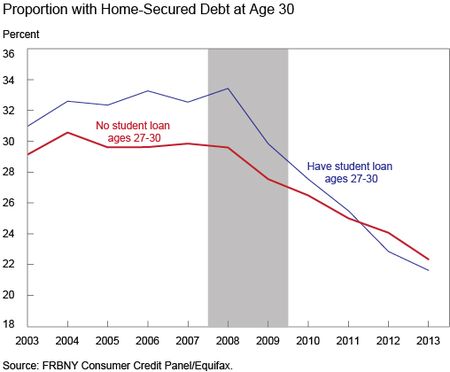

The first post-schooling economic activity we explore is homeownership. The chart below shows the trends in the rates of (inferred) homeownership over the last decade for thirty-year-olds with and without histories of student debt.

Despite an 11 percent house price recovery over the course of 2013 and an increase in overall mortgage debt, thirty-year-olds with and without student loans continued to retreat from the housing market.

Further, student borrowers failed to exhibit the differential recovery one might expect in 2013. Prior to the most recent recession, homeownership rates were substantially higher for thirty-year-olds with a history of student debt than for those without. This pre-recession pattern is typically explained by the fact that student debt holders have higher levels of education on average, and hence, higher income potential. Simply put, these more educated, often higher-earning, consumers were more likely to buy homes by the age of thirty.

However, the recession brought a sudden reversal in this relationship. As house prices fell, homeownership rates declined for all types of borrowers, and declined most for those thirty-year-olds with histories of student loan debt. In last year’s blog, we reported that 2012 was the first time in at least ten years that thirty-year-olds with no history of student loans were actually more likely to have home-secured debt than those with a history of student loans.

Did student borrowers regain their homeownership advantage in the course of the broader recovery? They did not. Surprisingly, student loan holders were still less likely to invest in houses than nonholders in 2013, despite the marked improvements in the aggregate housing market.

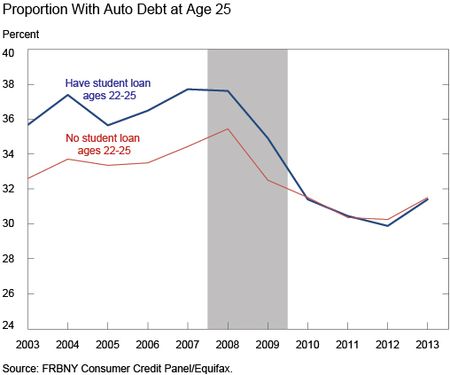

The next chart presents auto debt market participation among twenty‑five‑year‑olds. As discussed in the previous post, auto debt offers an informative, if incomplete, picture of young consumers’ participation in new and late-model used auto markets. The trends through 2012 for student borrowers and nonstudent borrowers in the auto market followed a similar pattern to that observed in the housing market.

Unlike housing market participation, however, auto market participation in 2013 began to improve for young people regardless of whether they had student loan debt. Further, the levels and trends of auto debt were roughly identical for twenty-five-year-olds with and without student loans from 2010 through 2013. While the broad return of twenty-five-year-olds to debt-funded auto purchases is certainly positive news for auto markets, it is surprising that (comparatively skilled) student loan holders have still not shown signs of accelerating auto consumption.

One possible reason for the failure of student borrowers’ housing and auto consumption to return to pre-recession levels is the growing burden of student debt. As reported in the previous post, the total debt per capita of student borrowers and nonstudent borrowers followed approximately parallel increases during the boom and approximately parallel declines during the Great Recession. In 2013, student borrowers did experience a small uptick to $30,227 in average total debt from $29,872 in 2012. This marks their first increase since 2008. The debt of nonstudent borrowers continued its decline from 2012 to 2013. Hence there is now a noticeable divergence in the total debt of student borrowers from nonstudent borrowers, as we might have expected all along.

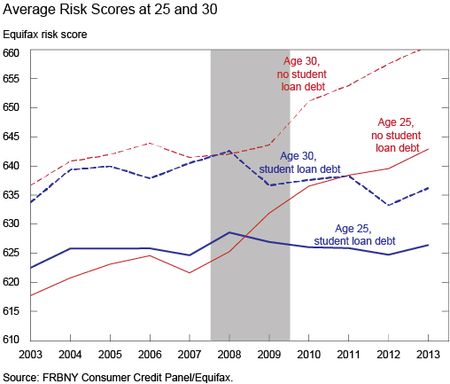

A second candidate explanation for the failure of these comparatively skilled student borrowers to consume more from debt is limited access to credit. Indeed, our previous post revealed a substantial recession-era divergence between the Equifax risk scores of student borrowers and nonstudent borrowers, favoring nonborrowers. The news for 2013, shown in the chart below, is that the average risk scores of student borrowers and nonstudent borrowers at ages twenty-five and thirty each increased by 2 or 3 points. The positive momentum in credit scores for all types of young borrowers, and the popular return to debt-funded auto purchases, represent perhaps the most promising green shoots to emerge from this analysis.

However, the failure of young consumers, and particularly the comparatively skilled young consumers of our student loan group, to re-enter the housing market remains a puzzle. Many factors could be contributing to this phenomenon, including growing student debt balances, limited access to credit, lowered expectations for future earnings, and perhaps even a cultural shift by which young people—whether they went to college or not—are deferring home purchases. Whatever the cause of student borrowers’ reticence, the housing market rebound of 2013 appears to have proceeded without the help of this skilled set of young buyers.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Meta Brown is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sydnee Caldwell is a former senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

Sarah Sutherland is a senior research analyst in the Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Did this analysis cross-reference the change in wage earnings for this age group over time? Given the apparent stagnation of wages for college grads, a big chunk of the “puzzle” should be explained simply by lack of buying power, aggravated by increasing debt load. If that is not the case, it would be noteworthy.

A third candidate explanation is that young people with college educations are more likely to uproot and move to pursue their careers. With this growing trend in mobility coupled with economic uncertainty, a non-negligible number of young people may be less willing to invest in large illiquid assets.

Quick question: how do you handle multiple person households (including married households) in calculating your “inferred” homeownrship rates?