In a recently released New York Fed staff report, we present a forward-looking monitoring program to identify and track time-varying sources of systemic risk. Our program distinguishes between shocks, which are difficult to prevent, and the vulnerabilities that amplify shocks, which can be addressed. Drawing on a substantial body of research, we identify leverage, maturity transformation, interconnectedness, complexity, and the pricing of risk as the primary vulnerabilities in the financial system. The monitoring program tracks these vulnerabilities in four sectors of the economy: asset markets, the banking sector, shadow banking, and the nonfinancial sector. The framework also highlights the policy trade-off between reducing systemic risk and raising the cost of financial intermediation by taking pre-emptive actions to reduce vulnerabilities.

The remainder of this post summarizes the main points of the staff report. We first provide a few examples of measures of vulnerabilities that could be tracked in each of the four sectors named just above. We then turn to potential policy responses.

Asset Markets

The main goal of monitoring asset markets is to detect signs of overvaluation as indicated by compressed required returns (that is, a low price of risk). An asset price that is boosted by a compressed price of risk is prone to drop, and the drop may be particularly severe and constitute a risk to financial intermediation if the valuations are supported by excessive leverage, maturity and liquidity transformation, or lax underwriting standards.

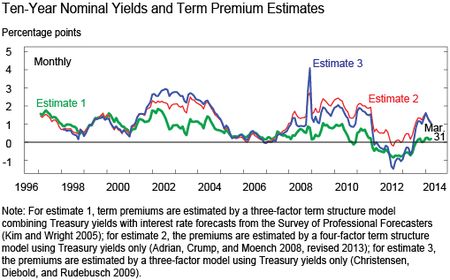

The standard way to gauge valuation pressures is with measures of risk and term premiums, with low premiums indicating compressed valuations. Valuations are also informed by nonprice measures, such as underwriting standards, the use of covenants, and issuance patterns. Our staff report discusses valuation measures in a wide range of markets. Consider, for example, the three measures of term premiums shown in the following chart (estimate 1, estimate 2, and estimate 3).

Despite differences in assumptions and estimation, the three term premiums on ten-year Treasury yields in the chart track each other closely. The term premiums exhibit a pronounced compression in the run-up to the financial crisis between 2003 and 2006, widened during the crisis from 2007 to 2009, stayed elevated through 2010, and then dropped to historic lows with the implementation of the Federal Reserve’s asset purchase programs. More recently, the estimates have risen, but remain compressed relative to historic norms.

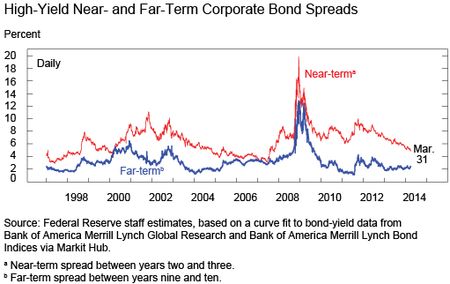

Another example, shown below, is a far-term yield spread on corporate bonds. Risk premiums on corporate bonds can be approximated by far-forward spreads, under the reasonable assumption that investors do not alter their assessments of expected default and recovery rates many years into the future. In the plot, high-yield forward spreads between nine and ten years ahead were quite low in 1997 and 2004-05, periods during which corporate bonds may have been overvalued. Current levels of the far-term spread are also low by historical standards, suggesting that risk premiums in the corporate bond market are compressed.

Banking

Systemically important banks are defined as banks that, when in distress, could disrupt the functioning of the broader financial system and harm the real economy. Firms are more likely to become systemic if they expect government support in failure, deploy excessive leverage, fail to internalize private-sector coordination failures associated with short-term debt that can contribute to fire sales and contagion, or are excessively interconnected to other parts of the financial system.

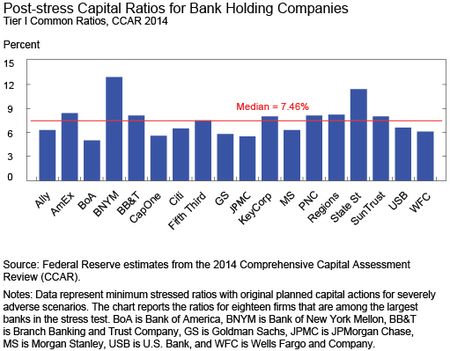

An important measure of banking vulnerability is the set of forward-looking capital ratios based on annual macroeconomic stress tests conducted by supervisors for the largest banking firms. The stress tests are used to assess whether these firms would have sufficient capital to withstand unexpectedly weak economic and financial conditions. Supervisors project losses for the firms’ loans, trading assets, and revenues based on detailed confidential information about each firm’s assets and business models. For the 2014 exercise (shown below), the projected capital ratios, including the capital distribution plans provided by the firms under the Comprehensive Capital Assessment Review (CCAR), indicate that each of the largest banks exceeded the 5 percent threshold for a tier 1 common ratio over the two-year projection horizon under the severely adverse scenario. In contrast, the original stress tests, initiated at the height of the financial crisis in 2009, indicated that ten of the nineteen firms needed to raise equity.

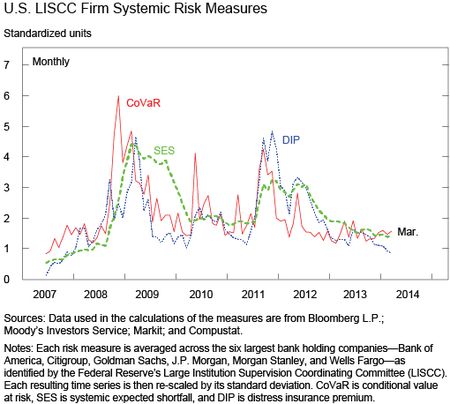

Our staff report also offers three market-based systemic risk measures, plotted below.

The first systemic risk measure, conditional value at risk (CoVaR), estimates the value at risk of the financial system conditional on a firm’s distress, based on co-movement of equity prices in the lower tail of the firm’s and the market return distributions. The distress insurance premium, or DIP, measures the cost of insuring a firm against systemwide distress, measured by losses on a portfolio of financial institutions. A third measure, the systemic expected shortfall, or SES, estimates the expected decline in the market value equity of a firm given a marketwide decline in equity prices, and so approximates the propensity to be undercapitalized coincident with the rest of the financial system. All three measures are currently low by historical standards. However, these measures also reflect the varying market price of risk, and so their low levels may be driven by low investor risk aversion rather than low vulnerabilities in large banks. Stress test measures, of course, are not affected by the market price of risk.

Shadow Banking

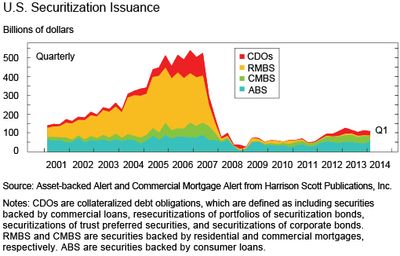

Shadow banking involves financial intermediation—including credit, liquidity, and maturity transformation—without an explicit government backstop. Our staff report offers a number of different measures of vulnerabilities in various parts of the shadow banking system. One important perspective is obtained from the volume of securitizations, as securitization is a core activity in shadow banking maturity transformation chains. The next chart shows that securitization volumes peaked prior to the financial crisis, plummeted during the crisis, and have remained well below pre-crisis levels since then.

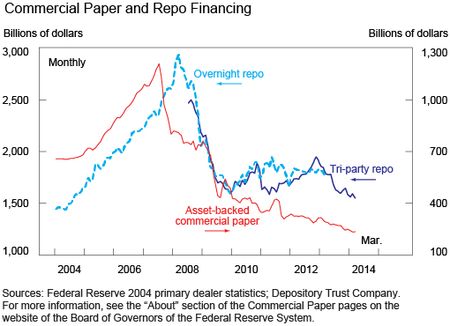

Another perspective on shadow banking is provided by the outstanding levels of short-term funding in the form of asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) and repurchase agreements (repos), which are also part of shadow banking maturity transformation chains. As indicated below, ABCP and overnight repo volumes rose sharply in the run-up to the financial crisis, and have declined significantly since then. ABCP peaked in August 2007 (corresponding to the onset of the financial crisis), while repos peaked in September 2008, about a year later. During the financial crisis, both fell sharply. Since then, outstanding tri-party and overnight repos have been about flat, while the level of ABCP has continued to trend down.

Nonfinancial Sector

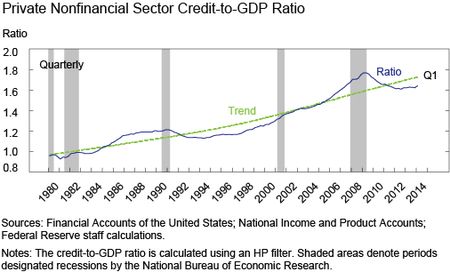

Researchers have identified excessive credit in the private nonfinancial sector as an important indicator of systemic risk. The chart below shows an aggregate measure of leverage for the private nonfinancial sector—the sector’s credit-to-GDP ratio—together with a trend line. This ratio has been flat over the past few years and well below trend, suggesting that the nonfinancial sector might not be an important vulnerability in the current environment.

However, firm-level data should also be monitored because they provide valuable information about changes in the weaker parts of the nonfinancial sector, which could be masked in aggregate measures. In fact, nonfinancial corporate leverage has been increasing recently, albeit from historically low levels.

Policy Responses

Time-varying financial vulnerabilities can in principle be addressed with macroprudential policies. However, these policies are not without costs; making the financial system more stable will likely increase the cost of credit to households and nonfinancial businesses.

Our staff report discusses several potential policies for addressing time-varying financial vulnerabilities, including countercyclical capital buffers at banks, generally higher capital requirements at banks, supervisory guidance for banks to tighten underwriting standards or to boost margin requirements on secured funding transactions, and tightened supervisory stress testing of systemically important financial institutions. Broader polices, such as greater disclosure and tighter monetary policy, are also discussed.

In our paper, we assert that targeted policy may reduce vulnerabilities in the short run but in the long run may push financial intermediation into less regulated parts of the financial system. We also argue that disclosures are needed to facilitate monitoring but will do little to mitigate the emergence of vulnerabilities. Further, we make the point that the incorporation of financial stability into the Fed’s dual mandate of achieving maximum employment and stable prices requires considering how financial vulnerabilities might affect downside risks to economic activity and inflation.

Given these considerations, our staff report suggests that a prudent path forward is a program for monitoring systemic risks, based on improved data collection and possibly enhanced disclosure, and the implementation of targeted supervisory policies to mitigate specific emerging risks. When excesses appear to be broad, or if targeted policies push vulnerabilities into more difficult-to-control parts of the financial system, the use of monetary policy to reduce vulnerabilities might also be appropriate, as has been recently laid out by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Tobias Adrian is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Daniel Covitz is an associate director in the Research and Statistics Division of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Nellie Liang is the director of the Board of Governors’ Office of Financial Stability Policy and Research.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics