Jonathan McCarthy

One contributor to the subdued pace of economic growth in this expansion has been consumer spending. Even though consumption growth has been somewhat stronger in the past couple of quarters, it has still been weak in this expansion relative to previous expansions. This post concentrates on consumer spending on discretionary and nondiscretionary services, which has been a subject of earlier posts in this blog. (See this post for the definition of discretionary versus nondiscretionary services expenditures and this post for a subsequent update.) Discretionary expenditures have picked up noticeably over recent quarters but, unlike spending on nondiscretionary services, they remain well below their pre-recession peak. Even so, the pace of recovery for both discretionary and nondiscretionary services in this expansion is well below that of previous cycles. One explanation is that weak income expectations continue to constrain household spending.

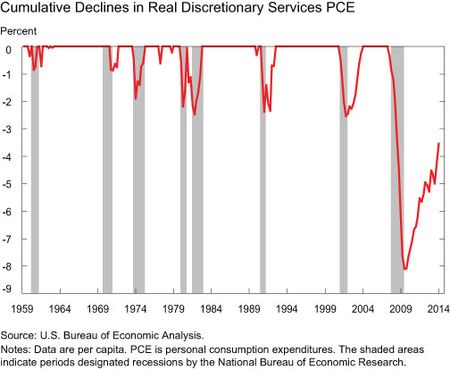

The chart below shows the extent of the decline in real per capita discretionary services expenditures from their previous peak—a zero value in this chart indicates that expenditures are above their previous peak. Although the process has been halting at times, these expenditures have continued to recover from the extraordinary decline (more than 8 percent at the trough) during the Great Recession. In particular, the recovery over 2013:Q4 and 2014:Q1 has been sizable, moving from about 5 percent below the previous peak to about 3½ percent—among the more rapid improvements since 1959. However, it is also evident that the recovery in these expenditures still has a considerable way to go to return to pre-recession levels: 3½ percent below the previous peak is still considerably worse than the troughs of previous business cycles.

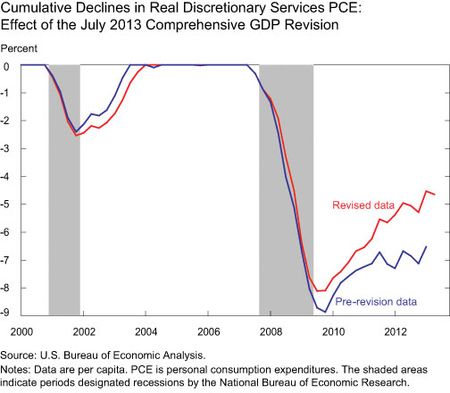

The picture is brighter than it was in the previous post in part because of the comprehensive revisions of previously released GDP data. The following chart illustrates the extent of the upward revision, which stems largely from higher estimated insurance expenditures.

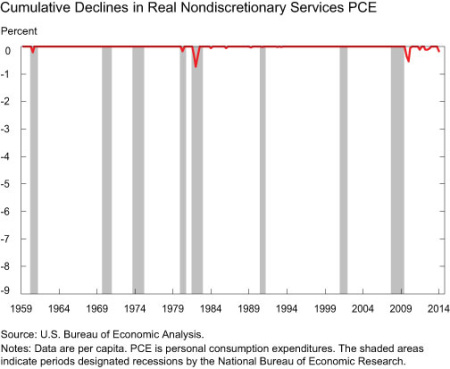

The next chart considers nondiscretionary services expenditures. The fall in these expenditures in the past recession was much less than that of discretionary services expenditures, and was not extraordinarily large compared with previous declines in nondiscretionary services. Even though nondiscretionary expenditures dropped somewhat in 2014:Q1—in large part because of the decline in health care expenditures in the quarter—these expenditures still have exceeded their pre-recession peak over the past several quarters. These patterns indicate that, consistent with the intuition behind these labels, households responded to severe income declines by cutting back on spending for discretionary services while maintaining spending for nondiscretionary services.

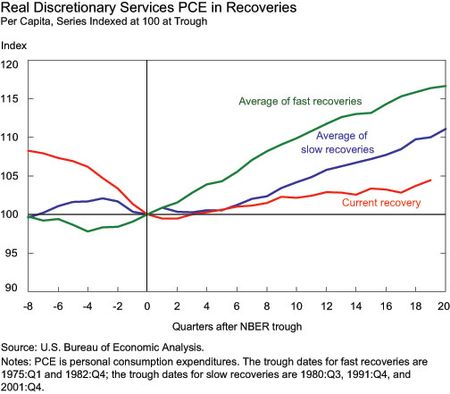

The pace of recovery for both discretionary and nondiscretionary services spending has been unusually slow in this expansion. The charts below present an index of real per capita services expenditures that equal 100 in the quarter at the end of a recession—a measure that allows a comparison of this recovery to “fast” recoveries (the average of those following the 1973-75 and 1981-82 recessions) and “slow” recoveries (the average of those following the 1980, 1990-91, and 2001 recessions). The first chart shows that the pace of recovery in discretionary services spending trails the average slow recovery by a considerable margin. As of 2014:Q1, almost five years after the end of the recession, these expenditures were only 4.4 percent above their level at the recession’s trough. In contrast, at this point in the average slow recovery, these expenditures were 10.0 percent above the level at the recessions’ trough, and in the average fast recovery, 16.4 percent.

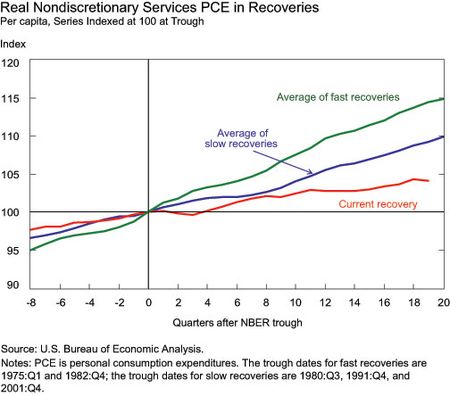

Nondiscretionary services spending has also been sluggish in this expansion relative to previous expansions. The level of these expenditures in 2014:Q1 was 4.1 percent above the level at the last recession’s trough, compared with 9.2 percent for the average slow recovery and 14.4 percent for the average fast recovery at the same stage of the cycle.

<br /

The sluggish pace of recovery for both discretionary and nondiscretionary services expenditures suggests that the fundamentals for consumer spending remain soft. In particular, it appears that households remain—almost five years after the end of the recession—wary about their future income growth and employment prospects. Consequently, a positive resolution of these issues seems necessary before a stronger services and overall consumer spending recovery can be sustained.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jonathan McCarthy is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

It’s not just income expectations, it’s actual incomes! After all, an unprecedented share of income gains has been going to profits instead of worker compensation, ever since around 2000, and compensation gains have fallen short of what would be expected from productivity gains, even when consistently measured. For those consumers unable to benefit from gains in asset prices, this must be a deterrent to discretionary spending. Cornelia Strawser Editor, Business Statistics of the United States (Bernan Press)

While consumer spending on services (discretionary and nondiscretionary) has been subpar, their spending on goods has been quite normal compared with past cycles. Consumer “wariness” on jobs and income is not evident in their goods spending patterns. It would be enlightening to find why spending on services is particularly weak in this recovery, since services expenditures are typically perceived as more stable than goods purchases.

I think you might find some of this explained by the aging population as services spending growth slows in older age groups as does necessity spending in general. Also wondering what population you used for the per capita as population growth has been lower than estimated.