Commercial banks didn’t become eligible for S-Corporation status until 1997, when President Bill Clinton signed legislation (the Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996) that allowed commercial banks to select S-Corporation as their preferred tax status. In this post, we discuss the features and history of S-Corporations, as well as the effect of lifting the restriction on banks’ organizational tax choice.

What is an S-Corporation?

S-Corporation status, created by Congress in 1958, allows companies to essentially retain their corporate form, but unlike C-Corporations, be treated as partnerships for tax purposes, effectively eliminating the double taxation of dividends and capital gains. That is, profits from an S-Corporation aren’t taxed at the corporate level; instead, they are passed through the corporate entity to shareholders on a pro rata basis and taxed only at the personal level.

While S-Corporation status has tax benefits, S-Corporations are subject to a number of restrictions that don’t apply to C-Corporations—they can only issue one class of stock, they are limited to certain types of shareholders, and, most notably, there is a limit on the number of shareholders. The number of shareholders was originally capped at ten but that limit was increased to fifteen in 1976, twenty-five in 1981, thirty-five in 1982, seventy-five in 1996, and one hundred in 2004. Higher shareholder limits, in addition to making more businesses immediately eligible, facilitate the bequeathing of small business stock to multiple heirs.

More than 60 percent of all corporations were S-Corporations in 2003, the most recent year for which figures are available.

How did banks get S-Corporation status?

When Congress first created S-Corporations, it excluded commercial banks from the list of eligible institutions because the banks already derived tax benefits from using the reserve method of accounting for bad debt. By 1993, banks began to challenge this exclusion on the grounds that their tax benefits associated with reserve accounting had been eroded. Community banks also said they were disadvantaged relative to credit unions, which are tax exempt, and at risk of being taken over by national banks that benefitted from various economies of scale and scope.

With the passage of the Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996, all depository institutions, except for thrifts and commercial banks with assets of less than $500 million that also employ the reserve method of accounting for bad debts, can organize as S-Corporations, subject to the constraint on the number of shareholders.

How many S-banks are there?

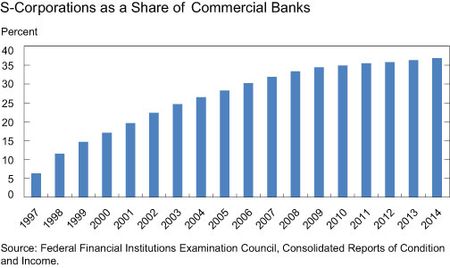

The figure below shows that the number of banks electing S-status, or S-banks, rose quickly. In 1997, the first year in which commercial banks could file as S-Corporations, 607, or more than 6 percent of all banks, did so. Currently, 2,148 banks have S-status, or more than 36 percent of all commercial banks.

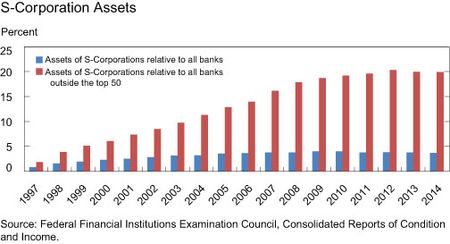

S-Corporations currently account for 3.7 percent of total banking industry assets (see below). Excluding the fifty largest banks, S-Corporations account for a more sizable 19.9 percent of aggregate commercial bank assets. As a rule, the higher the percentage of corporate income to be distributed, the more beneficial it is to elect S-status. So the S-Corporation best benefits an existing profit-making corporation that doesn’t reinvest earnings, or cannot do so because of an accumulated earnings problem, and expects to distribute substantially all of its income to shareholders.

Three legislative changes had the potential for large impacts on depository institutions that had become S-Corporations. The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 reduced personal marginal tax rates, lowering the highest bracket to 35 percent by 2003. The Jobs and Growth Tax Relief and Reconciliation Act of 2003 reduced the tax rate on qualified dividends and capital gains to 15 percent. The American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 raised the maximum number of allowable shareholders for S-Corporations to one hundred from seventy-five. Lower personal marginal tax rates relative to corporate marginal tax rates make S-Corporations more attractive. In contrast, the reduction in dividend and capital gains tax rates reduces but doesn’t eliminate the tax advantage of S-Corporations relative to C-Corporations. Increasing the number of allowable shareholders for S-Corporations expands the pool of eligible commercial banks.

S-Corporation banks provide a useful laboratory to formulate policy-relevant research. Given their limited access to equity markets, do S-banks have higher capital? Do they pay less in dividends? Can they absorb shocks better than C-Corporations or limited liability companies (LLCs)? A detailed analysis of the effects of allowing commercial banks to elect S-Corporation status can be found in this Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff report. In the report, Hamid Mehran and Michael Suher study the effect of S-status conversion on bank dividend payouts. The authors also examine how S-Corporation status affects a community bank’s likelihood of being sold, and they measure a firm’s sensitivity to tax rates based on its choice of organizational form. They document an increase in dividend payouts and a decreased likelihood of selloff compared to C-Corporations. The authors also estimate a tax rate elasticity of conversion in the range of 2 to 3 percent for every 1-percentage-point change in relative tax rates.

The limit on the number of shareholders allowed for S-Corporations tends to keep these banks small, but that isn’t a bad thing. As noted in a speech by Federal Reserve Governor Jerome Powell, community banks (those with less than $1 billion in assets) play a vital role in our financial system, providing essential services to households and small businesses that may otherwise be neglected. It is possible that S-status is important in preserving community banks during an era of bank consolidation. The debate over the role of community banks, as well as the results from Mehran and Suher, show that the 1996 legislation allowing for greater choice in organizational forms is one of the most important legal changes in recent history for commercial banks.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rajlakshmi De is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Hamid Mehran is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael Suher is a research fellow at the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics