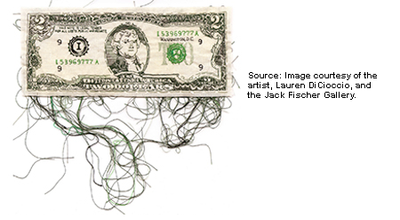

Lauren DiCioccio, a mixed media artist, sews (in the sense of embroiders) money. She has created a remarkable Colombian 5,000 peso bill, a Hong Kong 20 dollar bill, a 10 euro bill, and various versions of U.S. paper currency (when it was still just green). Her creations cannot be used as legal tender and, although quite realistic, could never be confused with legal tender—She leaves the uncut colored threads hanging out from behind each piece as if to say, Yes! This is sewing!

Another artist, Mary Temple, uses uncut bill sequences from the U.S. Treasury, changes the images, and then sews these together. Here is a sewn money hat by yet another artist.

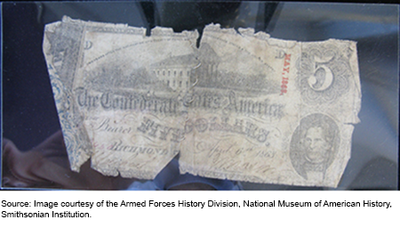

However, in history there were a few times that “sewn money,” (or, more correctly, “sewn-together money”) was in fact used as legal tender. In the American Revolutionary period, it was done to preserve disintegrating currency, and in the time of the American Civil War, it was a case of stitching together almost worthless (for both monetary and physical reasons) legal tender with more of the same to create usable legal tender. A National Museum of American History blog entry from November 2009 entitled “Money talks” describes a situation in the Civil War South when there was such dramatic inflation that paper money was not worth carrying around unless attached (bound with tape or paper or sewn) together. See a Confederacy five-dollar note with heavy gluing (sixth image at bottom of screen). The blogger describes encountering examples from the “Richmond Hoard” (a huge stash of Confederate paper money now at the Smithsonian):

I’d seen some examples of the patched-together (even sewn-together!) bills that his staff and volunteers uncovered. But I had no idea just how many stories—how much HISTORY—could be told by the oddities they found. For example, he [Richard Doty, senior curator of the National Numismatics Collection at that time] told me that inflation had become so bad by 1864 that bankers and others were batching low-denomination notes together in groups (a hundred fives, a hundred tens), because traded in that fashion, the notes still had reasonable value.

The story of the Richmond Hoard is an interesting one, even though it deals more with gluing than sewing. In this fascinating podcast (or here), Richard Doty (the curator mentioned in the quotation above) explains how the hoard came to the Smithsonian and describes the hyperinflation and the need to preserve the disintegrating paper money supply as two reasons for this gluing and sewing:

We’re dealing entirely with paper money here and paper money falls apart. . . . In order to keep the paper in circulation, people started gluing the darndest things onto it—backing it with various things, like a piece of newspaper, a little bit of glue, slap in on the back of the note and the thing will be kept in circulation. . . . Anyway it gets out of your hands and it’s somebody else’s problem. . . . They used other people’s paper money which had gone out of business, they used postage stamps that had glue on them. . . . They used in one case the front page from a bible, they used a map, they used telegrams, they used letters . . . as long as it would hold glue and hold a note together they would do it, and this gets into a thing of social history here and local history because you can learn a lot from what these people used and why they used it . . . . But there’s more than that. When you see a Confederate dollar bill carefully pasted together and the thing is dated 1862 and this is 1864, so it comes and it’s cancelled . . . it’s not worth anything by that point, so why are you going to the trouble of reinforcing it and keeping it in circulation? And the answer is that money is more than just money. It is an attribute of sovereignty. You see the same thing with Continental currency back during the Revolution. . . . It wasn’t worth anything, but people sewed it together, so help me, they actually did, and the reason that you did that in both cases . . . was because, if you said all right, the heck with it, it’s worth nothing anyway, forget it, throw it away, what did that say about your belief in the chances of your country, the chances of the Confederacy, actually making it? It was better to glue it together and put it back in circulation and hope for the best.

An interesting difference between this episode of hyperinflation and more recent episodes in history is that in the Civil War case, people did not start using their low-value paper money for toilet paper or children’s building blocks. They were too desperate for paper currency to waste it. You can read a synopsis of the 1861-65 hyperinflation in the Confederate States in an overview of periods of hyperinflation in history from San José State University.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Amy Farber is a research librarian in the Federal Reserve

Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics