Last year, IntercontinentalExchange (ICE) launched a credit default swap index futures contract. In the first two weeks there were spurts of interest in it, but soon it became evident that the new product was unable to generate sufficient demand. Given their short life span in the credit default swaps (CDS) market, the question becomes why were these futures contracts launched in the first place? And, assuming that they were created in response to a real need of market participants, will we see a revival of swap futures in the future?

Flight to Futures: Energy and Interest Rate Swap Markets as a Harbinger

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act overhauled the swaps market and mandated central clearing, trading, and reporting of swaps. These new regulatory requirements, combined with higher capital requirements, have increased the costs of trading swaps. In response, market operators have begun to move swaps trading into futures. Swaps are customized, bilateral contracts that exchange two streams of cash flows. The exchange traded futures are a promise to provide something (such as a physical commodity or shares in the S&P 500) at a pre-determined date in the future. The new hybrids, swap futures, promise to deliver a swap (or its cash equivalent) at maturity. Although these contracts provide exposure similar to swap contracts, they benefit from reduced margin requirements because they are traded on futures exchanges.

The first provider to jump on the bandwagon was ICE. When the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) announced on October 12, 2012, who would be treated as a swaps dealer for regulatory purposes, ICE took all the energy swaps and options that had been trading on its electronic marketplace—more than 800 contracts—and used them to create futures contracts that could trade on its futures exchange. ICE’s conversion of swaps and options into futures meant users of those products wouldn’t need to count that activity towards their CFTC registration. Other exchanges took similar steps, and in December 2012, CME Group began offering deliverable U.S. dollar interest rate swap futures, and ERIS Exchange also began offering a cash-settled U.S. dollar interest rate swap futures.

Given the successful adoption of these hybrid contracts in the energy and interest rate markets and the stricter regulatory environment, the CDS market seemed ripe for “futurization” as well.

How did CDX swap futures work?

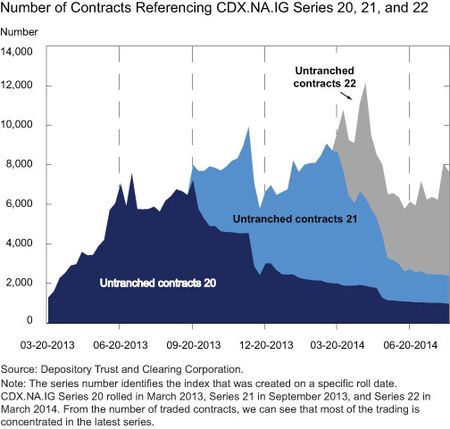

ICE decided to launch a futures contract referencing the Markit CDX North America Investment Grade index (or the CDX.NA.IG index). Unlike the CDX index, which provides credit protection on a basket of firms, the CDX swap futures traded the expected future price of the CDX index. Due to the nature of the CDS contracts and the inherent risk of credit deterioration, the CDX.NA.IG index is “rolled” into a new series every six months, as illiquid and low credit constituents are replaced by more relevant firms. As the soon to be off-the-run series index is rolled to a new on-the-run series, liquidity migrates to the on-the-run index (see the chart below). The changing composition of the index complicates the construction of a futures contract on the CDX index. To circumvent the inherent difficulty of pricing a contract that is contingent on credit events in the underlying reference entities prior to the maturity date, ICE decided to construct the contract as a “when-issued” futures contract. Rather than referencing the on-the-run CDX index, the futures contract referenced the will-be on-the-run index, which has not yet been issued and whose constituents have not yet been determined (the final composition of the index is confirmed only one day prior to the launch of a new series).

This “when-issued” feature seems to be the main flaw in the contract’s design. It created uncertainty regarding the index composition at the time of entering new CDX swap futures trades. In anticipation of this difficulty, Markit revamped its inclusion and exclusion rules to be more deterministic and based on publicly available data; it also began publishing the components of a new index if the roll were to take place that day. Despite these attempts to resolve the uncertainty, investors were still left with the challenge of pricing contracts without fully knowing the underlying composition. The uncertainty cost of the “when-issued” feature seems to exceed the futurization “benefits” (reduced burden from registration and reporting requirements), putting an end to the CDX swap futures.

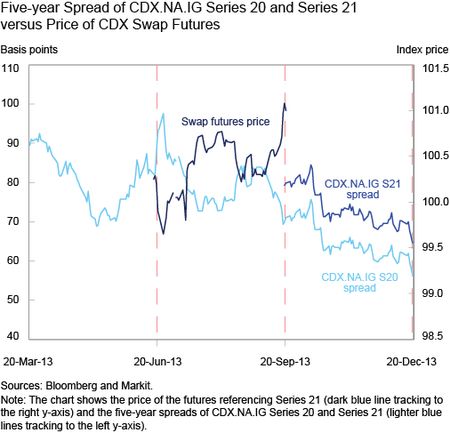

To get a sense of this “uncertainty cost,” let’s look at what happened around the September 2013 roll of the CDX.NA.IG index. We choose to focus on this particular roll because the when-issued CDS index futures were launched on June 17, 2013, and delisted on March 17, 2014. So, this is the only roll when the CDS futures existed. In the chart below we can see that the different composition and the six-month maturity extension of the index resulted in a 9 basis points differential between the on-the-run and the off-the-run at the roll, mostly attributable to the maturity difference. Coupled with the observation that the churn of names at each series launch tends to be limited (three new names entered Series 21 of the CDX.NA.IG index), it might seem that the uncertainty regarding the future expected price of the CDX index is not that high. However, this is not the case. There is uncertainty both about which constituents would exit the index and which new candidates would replace them. Going back to our example, from the date the new CDX swap futures were launched until the roll, Markit’s hypothetical list of constituents had been updated five times. The uncertainty would have been greater given that the futures contracts were planned to span an eight-month period.

Credit Swap Futures: Financial Innovation or Redundant Asset?

In his review of financial innovations from the mid-1960s to mid-1980s, Miller (1986) notes that “many of the financial innovations . . . already existed in one form or another for many years before they sprang into prominence. They were lying like seeds beneath the snow, waiting for some change in the environment to bring them to life.” So, are credit swap futures a dormant seed that will flourish in the future?

On the one hand, the success of swap futures in the energy and interest rate markets implies that the swap futures are able to make these markets more complete by allowing investment choices that were previously cost inefficient or impossible due to regulatory or institutional constraints (see, for example, Black [1986], Finnerty [1988], Allen and Gale [1994], Duffie and Rahi [1995], and Tufano [2003]). On the other hand, unlike the CDX index, the CDX index futures didn’t provide credit protection. It was essentially a trade on the future price of the index, which given the end result, was viewed as unnecessary by CDS market participants. All in all, the Dodd-Frank Act sparked regulation-and-subsequent-circumvention cycle (Kane 1988) that supported the successful adoption of futures in the energy and interest rates markets but was insufficient to support the CDX index futures’ viability.

The incentives to offer a cost-effective alternative to CDSs still exist, and unsuccessful attempts in the past did not discourage financial providers from trying to reinvent credit swap futures. (In March 2007, both Deutsche Börse and CME Group launched credit-related futures contracts that subsequently failed.) So, as long as the costs of trading futures are lower than the costs of trading centrally cleared swaps, incentives to develop a CDS futures contract will remain. The future success of such hybrid credit swap futures depends on the ability of a financial provider to design a contract that would successfully price in the probability that constituents might default.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Or Shachar is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Or Shachar is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

There’s already a product that prices credit risk, including default probability. That’s the CDS Index Swap which is why moving to a WI format failed. Most investors buy or sell IG CDS Indices to profit from spreads movement. Neither buyer nor seller really cares whether it is normal spread movement or a Credit Event occurs. The P&L is the same regardless of what drives the individual constituent’s credit spread movement. In a CDS contract, the CDS buyer profits from credit spread. In a WI contract, the buyer of protection will NOT benefit from spread widening if the issuer has a Credit Event or is downgraded so it cannot be included, or is excluded for any reason. So the CDS buyer on a WI contract takes on risks they don’t have in a normal contract. These arbitrary and binary risks reduce the demand from buyers of CDS, while at the same time not greatly changing the price sellers demand because “could” remain in the WI contract. That is why the bid/offer was large on the WI contract and why it didn’t act as a good alternative to existing CDS Index Swaps. For a financial product to be successful, it needs to have “arbitrage conditions” that can be captured and enforced by the market, but the WI contract did not have that, so it was not successful. Both investors and regulators will need to accept Credit Event risk as part of trading IG Index CDS (only 2 Credit Events in on the run index in past 10 years). They should accept it and over time this business should grow.