On June 24, 1968, thousands of people swarmed assay offices in the United States, anxious to unload their holdings of silver certificates. The U.S. Treasury had deemed this the final date on which the certificates could be exchanged for silver bullion. People camped out overnight to ensure that they would beat the deadline, and the resulting lines stretched for hours. Life Magazine covered the story, and offered a history of silver certificates in the United States.

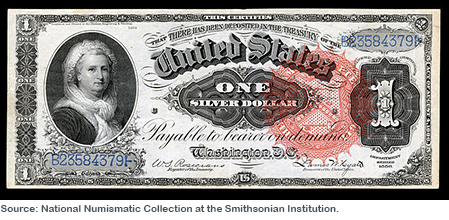

Silver certificates were the result of a once-bimetallic system—gold and silver—in the United States. Laws passed in the late 1800s required the U.S. government to purchase large quantities of silver and issue certificates backing their value. The certificates featured the images of a wide variety of people, including Martha Washington, the only woman to appear on a U.S. note. One of the required U.S. silver purchases, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, partially led to a financial panic in 1893.

By 1900, the bimetallic system had ended in the United States, and gold was the sole standard of value. However, silver certificates remained in use for decades, even after the end of gold certificates in 1933. In the mid-twentieth century, silver remained in high demand owing to the use of silver nitrate in photographic film, and the Treasury was forced to sell down its reserves to maintain a then-official price for silver. By 1964, silver certificates were no longer printed, and by 1965, the silver content of all U.S. coins except the half dollar was removed. It was then only a matter of time before the end of silver certificates and the resulting mob scenes at the assay offices in 1968.

To this day, outstanding silver certificates are still legal tender and can be spent exactly the same way as U.S. currency. Meanwhile, silver’s former partner in the bimetallic system—gold—remains a prominent investment option as well as the topic of a popular tour at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Megan Cohen is a research librarian in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics