In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, job transitions of personnel in banking supervision and regulation between the public and private sectors—often labeled the revolving door—have come under intense scrutiny and have been blamed by certain economists (Johnson and Kwak), legal scholars (John Coffee in the Financial Times), and policymakers (Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, Section 968) for distorting regulators’ actions in favor of banks. However, other commentators have downplayed these distortions and presented a more benign viewpoint of these worker flows—as a means for regulatory agencies to attract higher-ability and skilled workers. Because data on job transitions in banking regulatory agencies are scarce, these discussions are mostly informed by anecdotes. Our recent paper brings more rigor to this debate by contributing a first set of stylized facts based on data related to incidence and drivers of worker flows in U.S. banking regulation. Our data show clear evidence of higher worker inflows to the regulatory sector during bad economic conditions. When we study worker flows as a function of an enforcement proxy, we find evidence to be inconsistent with the often-cited “quid-pro-quo” hypothesis. We instead posit an alternative “regulatory schooling” hypothesis that may better explain the empirical evidence.

The Challenge

A large literature in labor economics has studied direct job-to-job flows (see Blanchard and Diamond and Fallick and Fleischman for seminal studies), employing longitudinal and cross-sectional data surveys. However, because banking regulators account for only a tiny fraction of all U.S. workers, none of these sample surveys is detailed enough to construct worker flow statistics for the regulatory sector. We circumvent the challenge of data sparsity by constructing a unique dataset of career paths of more than 35,000 former and current regulators across all agencies that regulate commercial banks and thrifts—the Federal Reserve Banks (Fed), the Federal Depository Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), and state banking regulators—that have posted their curricula vitae (CVs) on a major professional networking website. Our sample spans the past twenty-five years and provides a unique perspective into the process of selection and transition of personnel from these regulatory agencies to the private sector.

Basic Facts on Worker Flows between the Banking Regulatory and Private Sectors

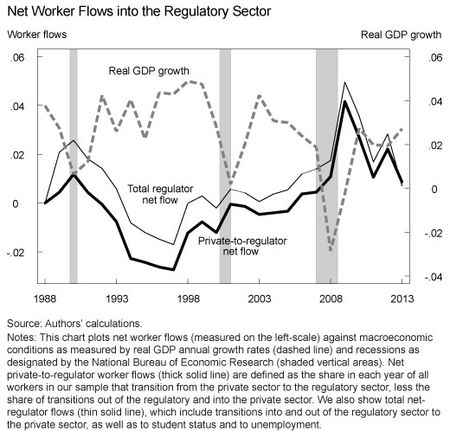

The data reveal clear evidence of countercyclical net worker inflows to the regulatory sector. In good times, net worker flows from the private sector to the regulatory sector fall significantly and are often negative, which may be the result of higher gross inflows to the regulatory sector in bad times or higher gross outflows from this sector in good times (see chart below).

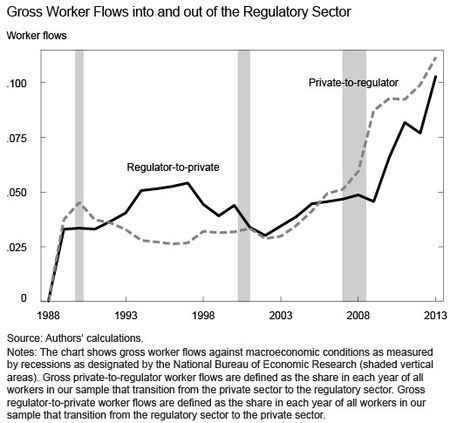

Additionally, the data show that higher gross outflows to the private sector during economic booms are a key driver of the countercyclical regulator net worker flows (that is, banking regulators move to the private sector when the economy is booming). We also find evidence of higher gross inflows to regulation in bad times in the past few years, likely due to strong regulatory demand linked to enhanced banking supervision following the post-2007 financial turmoil (see next chart).

We then study regulatory worker flows as demand-side proxies for job creation or destruction in the banking and regulatory sectors and find that transitions into the regulatory sector are positively related to measures of banking stress and inversely related to bank profitability (with opposite patterns for outflows). On average, gross worker flows between the regulatory sector and private sector are less than half the job-to-job transitions in the private sector, as measured from a benchmark sample of financial sector employees we employ and data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), which is a standard data source used to study private job-to-job flows. In other words, while job reallocations from the regulatory sector to the private sector exist, these flows are significantly lower than those measured for private-sector employees.

Next, using information from workers’ CVs and taking into account that our dataset is longitudinal, we examine the selection of individuals into and out of the regulatory sector by assessing which individuals enter and exit banking regulation over the business cycle, as a function of their human capital (that is, their education levels, as typically listed on CVs) and skills/connections (that is, their seniority in the regulatory organization based on occupations). We find that the best talent, as proxied by higher human capital, has shorter spells inside regulatory agencies because of higher outflows to the private sector. We also note that more senior staff, perhaps not surprisingly, spend more time in regulation. While we observe no significant differences in the business cycle sensitivity across different human capital levels, one can interpret the evidence as suggesting that the regulatory sector faces some retention challenges for workers with higher education. Also consistent with possible retention challenges, we further find that regulatory spells have been declining in the past twenty-five years. For example, while about 88 percent of workers that started working in regulation in 1988 spent three or more years working in regulatory agencies, only 64 percent of workers that started working in this sector did so two decades later.

“Quid Pro Quo” and “Regulatory Schooling” Hypothesis

The final part of our analysis explores aggregate regulator mobility as a function of regulatory actions. According to one prominent view—the “quid-pro-quo” view—future employment opportunities in the private sector affect a regulator’s strictness of actions while the individual is employed in the regulatory sector. This hypothesis implies that we should observe lower gross outflows from regulation to private banking during periods of high enforcement activity (or that laxity while working in regulation should be followed by an exit to the private sector, possibly in the form of a “valuable job position,” as quid pro quo). An alternative view of the revolving door—the “regulatory schooling” view—suggests that regulators may instead have an incentive (or at least not a disincentive) to favor complex rules because “schooling” in these regulations enhances the future earnings of regulators, should they transition to the private sector. That hypothesis implies high gross inflows to regulation at times of higher regulatory intensity as workers are schooled in the new rules as well as high gross outflows from regulation into the private sector as regulators earn returns from schooling in the new rules. According to the regulatory schooling view, inefficiencies may derive not from laxity, but rather from more complex regulations.

To shed light on these hypotheses, we relate worker flows to intensity of supervisory activity in the data. We measure each regulator’s strictness using their formal enforcement activity in a given state and year. We find a positive association between the intensity of strict actions over time and across states and the net inflows to the regulatory sector. Looking more closely at gross flows, we note that this relationship is driven more by inflows to the regulatory sector in periods of high enforcement/more intense regulatory activity. Gross outflows from the regulatory sector are, in fact, higher around periods of higher enforcemen

t activity.

This evidence is consistent with the regulatory schooling view and inconsistent with the quid-pro-quo channel, although our tests on this dimension are limited owing to availability of regulator-specific proxies of enforcement activity or of regulatory complexity, and we caution against taking these findings as conclusive. That said, we found consistent results in terms of the quid-pro-quo channel, and in particular the lack thereof, in our earlier work on state banking supervisors discussed in Agarwal, Lucca, Seru, and Trebbi.

Discussion

Some critics have proposed restricting the ability of regulatory personnel to transition to the private sector as well as tightening the hiring of industry insiders by regulatory agencies. However, our results suggest that the regulatory sector faces a retention challenge, as measured by the lower employment spells of regulatory personnel in more recent years and for workers with higher education. While more work is needed to quantify any regulatory impact induced by regulatory worker flows, our findings do suggest that tightening these flows without altering other aspects of worker incentives may further hamper the ability of regulatory agencies to seek and retain talent. Rather than seeing our study as definitive work studying flows of personnel between the regulatory and private sectors, we hope our contribution will spur more interest in an area that is begging for more research.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

David O. Lucca is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Amit Seru is a professor of finance at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

Francesco Trebbi is a professor of economics at the University of British Columbia.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics