The contribution of labor input to the potential GDP growth rate for the United States has changed over time. We decompose this contribution into two components: the size of the adult population and the average demographically adjusted employment rate. We find that these two components in the late 1960s and early 1970s contributed at least 2.5 percentage points to potential growth. Since the mid-1990s, the aging of the population has reduced the contribution of labor to growth. We estimate that the current contribution to potential economic growth from labor input has declined to around 0.6 percentage points. One implication going forward is that more labor productivity growth will be required to sustain U.S. growth.

To illustrate the contribution of labor input, we decompose potential growth in the following way:

Potential Growtht

≈ Adult Population Growtht + Demographically Adjusted Employment- to-Population Growtht + Trend Growth in Output per Workert

The first two components—growth in the adult population and growth in the demographically adjusted employment-to-population (E/P) ratio—capture the labor input to potential growth. Note that our last term is trend growth in output per worker and not output per hour. This means that any secular changes in average hours of work conditional on employment are captured in this variable.

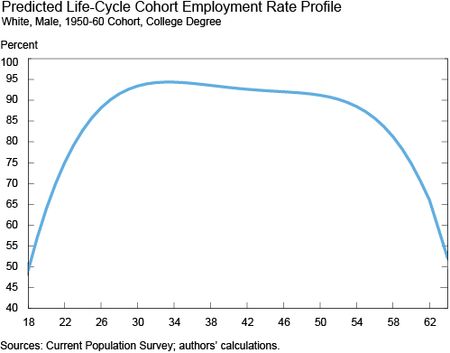

To implement this decomposition requires an estimate of the demographically adjusted E/P ratio over time. We divide the Current Population Survey (CPS) Outgoing Rotation Group sample, with approximately 13 million observations, into 320 cohorts based on birth cohort, sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. For each cohort, we abstract from cyclical effects and estimate the average probability of employment for each age. Aggregating these predicted employment rates across individuals in our data for each month to a single measure (using CPS sample weights) gives us the demographically adjusted E/P ratio. (For a more detailed discussion, see our earlier post, “A Mis-Leading Labor Market Indicator.”) The chart below shows one of the 320 estimated employment profiles that underlie the aggregate demographically adjusted E/P ratio.

As we can see, the predicted employment rate for this cohort rises with age until the mid-30s, remains relatively flat until the early 50s, and then begins to fall, with the rate of decline increasing around the age of retirement. We allow for level shifts around the ages of 62 and 65 to account for retirement, although no member of this specific cohort has yet reached the age of 65 (because the birth cohort is too recent). The demographically adjusted E/P ratio for the whole economy will reflect changes in the age distribution of the adult population over time, as well as changes over time in the levels of educational attainment.

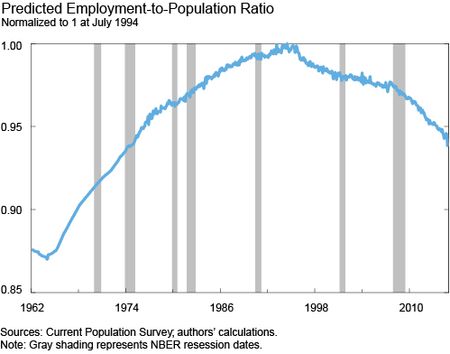

We update our CPS data from the previous post to include data from 1962 through December 2014. We can extend our CPS monthly data back to the mid-1970s with no change in methodology. From 1962 to 1975, however, we have data from the CPS March supplement only. Consequently, we linearly interpolate between these annual observation points from 1962 to 1975. The chart below shows the demographically adjusted E/P ratio, normalized to a value of 1 at its estimated peak in July 1994.

From the early 1960s to the mid-1990s, our estimated demographically adjusted E/P ratio rises strongly, reflecting both the integration of baby boomers into the labor market as well as the rise in the female labor force participation rate. From its peak in the mid-1990s to the present, the demographically adjusted E/P ratio is estimated to have fallen 5.9 percent, with the current value the same as in 1974.

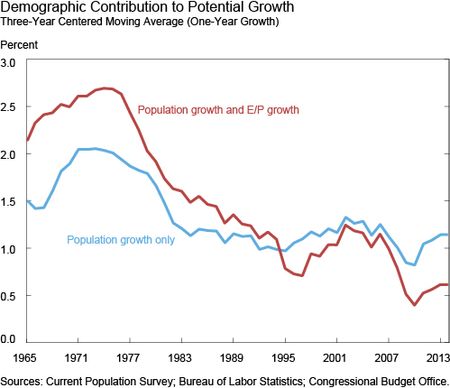

We can now estimate how much potential GDP growth over the past 50 years was affected by changes in the adult population and in the demographically adjusted E/P ratio. We plot these contributions in the chart below.

We can see that the estimated contribution of labor input to potential growth has varied over time. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, for example, labor input was contributing more than 2.5 percentage points to potential growth, with a substantial part of that owing to baby boomers entering the workforce. Over the next 40 years, the labor input contribution to potential growth steadily declined, with the current contribution estimated at only around 0.6 percent even though population growth has been steady since the early 1980s. The decline is caused by the demographically adjusted E/P ratio starting to fall in the mid-1990s, reflecting the aging of the baby boomers. The ratio is expected to continue to pull down the overall contribution of labor input to potential growth in the years ahead, as the population ages. That is, potential growth is no longer improving with age.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Samuel Kapon is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joseph Tracy is an executive vice president and senior advisor to the Bank president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Joseph Tracy is an executive vice president and senior advisor to the Bank president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

It can be argued that labor productivity is inversely proportional to job growth, unless you have an unlimited demand for product.

Joe and Sam, A 2nd thought if you want to do more work in this area. I’ve long thought that the dimensional reduction techniques Arnott uses in this paper to create demographic cohort curves could be useful in looking at issues like growth and savings across countries. https://www.researchaffiliates.com/Our%20Ideas/Insights/Fundamentals/Pages/F_2013_June_Mind-the-Expectations-Gap.aspx http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1810985 We know from research that peak savings and peak productivity occur at different points on the demographic cycle. By looking across countries, you might be able to infer plausible changes to balance of payments, or growth, or other comparative statics. …bp

Joe and Sam, You might be interested in this post at Calculated Risk. http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2015/05/part-ii-demographics-are-now-improving.html Key quote: “A decade ago it was obvious that demographics would be a drag on the economy. Even without the financial crisis, we would have expected a slowdown in growth. But now the prime working age population is growing again, and we can expect growth to pick up over the next decade.” Brian

Nice. A kink in E/P at 07 coinciding with the onset of a badly managed recession. It surely must be a durable trend not subject to policy. John