Since the financial crisis, major U.S. banking institutions have increased their capital ratios in response to tighter capital requirements. Some market analysts have asserted that the higher capital and liquidity requirements are driving up the costs of market making and reducing market liquidity. If regulations were, in fact, increasing the cost of market making, one would expect to see a rise in the expected returns to that activity. In this post, we estimate market-making returns in equity and corporate bond markets to assess the impact of regulations.

Returns to High-Frequency Market Making in Equities

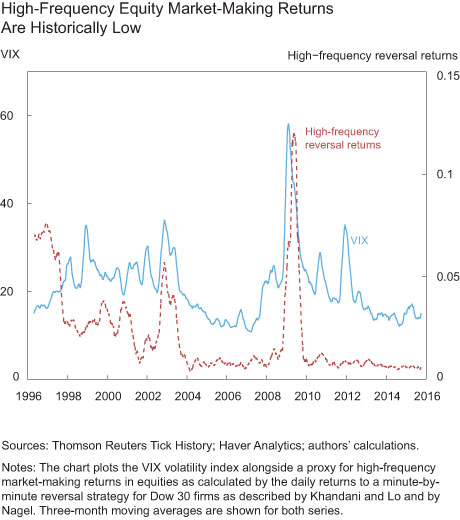

We start by calculating minute-by-minute returns from a reversal strategy for the thirty firms in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (using the methodology described by Khandani and Lo and Nagel). Returns are based on an investment portfolio that is long past losers and short past winners, thus betting on the reversal of past trends. The literature uses such reversal profits as proxies for expected returns to market making, as market makers tend to manage their trading book in a similar fashion. As shown in the chart below, profits on this reversal strategy declined precipitously between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s, and have since stabilized at historically low levels, except for a temporary increase during the financial crisis. While market-making returns were highly correlated with the VIX (the Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index) through 2004, they have been more stable than the VIX since then, except during the financial crisis when both the VIX and the returns increased significantly.

The decline in high-frequency market-making returns has occurred against a backdrop of increasing competition. The expected returns to high-frequency trading (HFT) in the 1990s encouraged large investments in speed and led many new firms to enter the sector—as documented in academic studies. The sharp decline in high-frequency profits over the first ten years of our sample suggests that these profits were gradually eroded by competition as the HFT sector developed. Importantly, market-making profits have not increased since capital and liquidity regulations were tightened following the financial crisis.

Day-to-Day Market-Making Returns in Equities

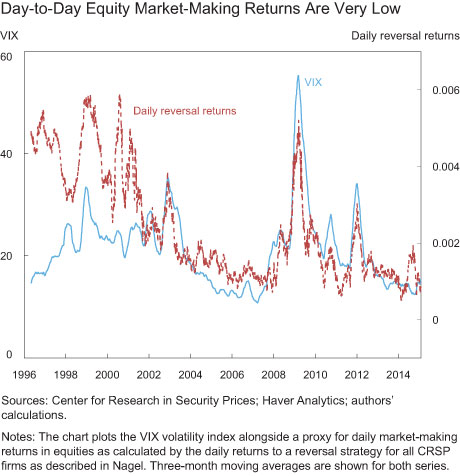

Between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s, day-to-day reversal trading returns declined for the firms tracked in the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) database, as shown in the next chart. While day-to-day reversal returns also increased sharply during the crisis, there is no discernible trend in profits since the mid-2000s.

The chart also shows a striking correlation between day-to-day market-making profits and the evolution of market volatility since the mid-2000s, a relationship not observed for higher-frequency market making. The interpretation is that higher market volatility tightens dealers’ funding constraints, contributing to a widening of market-making returns. Risk management techniques that rely directly on market volatility, such as VaR limits, can cause such funding constraints to bind and create a link between funding liquidity and market liquidity (Brunnermeier and Pedersen and Adrian and Shin).

Corporate Bond Market-Making Returns

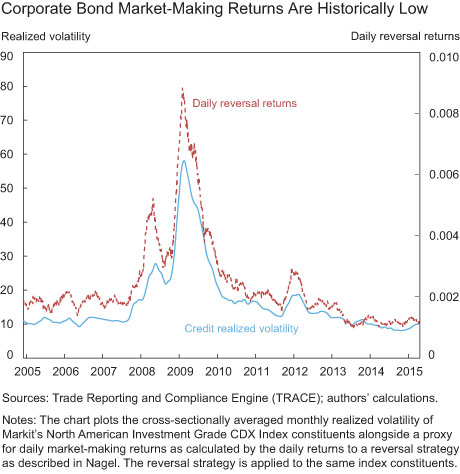

While dealers play a reduced role in equity markets, they remain the predominant market makers in the corporate bond market. Furthermore, capital regulations since the financial crisis have increased the risk weighting on corporate bonds. If it were true that these higher capital requirements were leading dealers to withdraw from market making, one would expect market-making returns to widen, especially in that market. However, as the next chart illustrates, reversal returns for corporate bonds show no such increase, and thereby do not suggest a withdrawal of market-making activity in this market. The chart also reveals a close relationship between returns to market making and corporate bond realized volatility, with returns to market making highest during high-volatility periods.

Hedge Fund Returns

Besides dealers and HFT firms, hedge funds are a third class of financial institutions that is likely to have a first-order impact on returns to market making. In fact, to some extent, hedge funds fulfill roles similar to market makers insofar as their trading provides liquidity. Furthermore, certain forms of trading—particularly proprietary trading—have been transferred from dealers to hedge funds. Jurek and Stafford show that an index of aggregate hedge fund sector returns can be replicated with a put writing strategy on the S&P 500 Index. Such a strategy performs well in normal times, but suffers large losses when volatility is high.

The insight that hedge funds are structurally short volatility means that we would expect the volatility risk premium to depend on the size of the hedge fund sector. Hence our earlier finding that the frequency of volatility jumps does not appear to be associated with the pricing of volatility risk (as measured by the volatility risk premium) might be explained by the growing size of the hedge fund sector. That is, while changes in market structure might have increased liquidity risk and vol-of-vol in some markets, the impact on the pricing of volatility risk might have been offset by growth in the hedge fund sector.

Dealer Returns

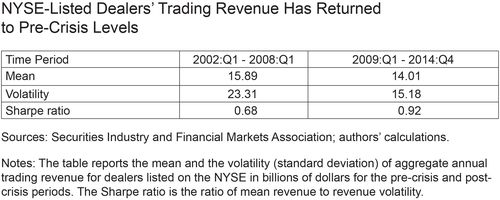

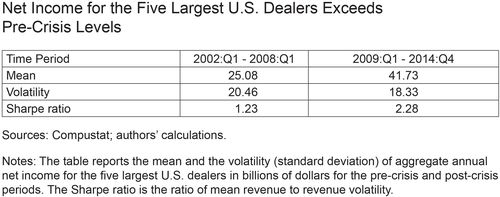

The evidence that expected returns to market making have remained compressed despite the tightening of capital and liquidity requirements raises the question of whether dealers have become less profitable. The answer is, perhaps surprisingly, not necessarily. Trading revenue for dealers listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) has been very close to pre-crisis levels (see table below), while the volatility of trading revenue has been much lower post-crisis. The Sharpe ratio of trading revenue (aggregate revenue of dealers divided by the volatility of revenue) has been considerably higher post-crisis.

Net income for the five largest U.S. dealers—J.P. Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley—has also been much higher and less volati

le since the crisis than before (see next table), and the Sharpe ratio of net income for the largest five dealers is nearly twice as high since the crisis (2.28 versus 1.23).

These trading revenue and income figures suggest that dealers continue to play a key role in liquidity provision. This is particularly important for less liquid securities such as corporate bonds and off-the-run Treasury securities, in which HFT firms are less active. Moreover, because of their customer relationships, dealers have more incentive to provide liquidity at times of stress. This crucial role of dealers has led some observers to argue that prudential regulations for dealers should be loosened. However, looser regulatory constraints would not relax the competitive pressure dealers face from the HFT and hedge fund sectors and could come at the cost of a less resilient financial system.

In Sum

We show estimated returns to market making to be at historically low levels—a finding that seems inconsistent with market analysts’ argument that higher capital requirements have reduced market liquidity. The picture that emerges from our analysis is of a change in the risk-sharing arrangement among trading institutions. We uncover a compression in expected returns to market making in the corporate bond market, where dealers remain the predominant market makers, as well as the equity market, where dealers are less important. The compression of market making returns may be tied to competitive pressures, with high-frequency trading competition being important in the equity market.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Tobias Adrian is the associate director of research and a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Michael J. Fleming is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Or Shachar is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Daniel Stackman is a Research Associate in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Erik Vogt is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for the various comments. In response to rc whalen, we find the returns to market making to be compressed, but positive. Moreover, such market making returns need not be earned by big banks alone, but by a variety of market participants, including hedge funds and high-frequency trading firms. In response to Srihari Angara, we agree, of course, that we’ve been in an exceptional monetary policy environment for some time. We also agree that multiple factors, including the evolving organization of the security-broker industry, may be affecting sector profits.

HFT, like the wire con, only works if only the scam artist has access to the high speed wire. The only real news is that there are still a few people who are surprised by the outcome as everyone has adopted HFT.

Dear Colleagues, There are no returns to market making. It is a loss leader at best. Since ZIRP has deprived dealers from making money on inventory or clearing balances, all of the pressure is on fees. Anybody who works for a large ibank would tell you this. Right? Best,

Kudos on fascinating research and findings. While the conclusion that higher bank capital ratios have not reduced bank profitability, there are a couple of unprecedented conditions that continue to exist post-crisis and the study is silent or does not seem to allude to those forces and factors. First, the phenomenal easing and multitude of operation twists have created near zero cost of funds. Second, the correlation between interest rates and issuance or rather explosion of corporate bond issuance by every rating segment of the companies ranging from junk to high grade issuers. Lastly the profits are despite high capital requirements that might be partly due to lower competition and high consolidation in the financial sector since the crisis.