When the U.S. Civil War broke out in 1861, cotton was king. The southern United States produced and exported much of the world’s cotton, England was a major textile producer, and cotton textiles were exported from England around the world. At the time, many around the world depended on cotton for their livelihood. The South believed this so deeply that when the North blocked Southern ports to cut off the South’s primary means of financing war—cotton sales—Southern leaders were sure that Britain would enter the war on their side. That never happened. So when cotton supplies dried up in late 1862, thousands in Manchester and Lancashire who either directly or indirectly depended on cotton for a living found themselves without work. In this post, we describe the British cotton famine of 1862-63 and the stoic British national response. We draw primarily from a fascinating BBC Radio broadcast on the subject and John Watts’ matter-of-factly named Facts of the Cotton Famine, published in 1866.

“Cottonopolis”

Textile production began in England as far back as the 1770s, though in a small way. But by the 1860s, up to one million people were working in one way or another with cotton, and up to four million—about a fifth of the British population—were estimated to be either directly or indirectly employed by the cotton industry. At the peak of production, there were nearly 2,500 textile factories in Lancashire, directly employing about 430,000 people, mostly women. The weaving of textiles was concentrated in Lancashire, while spinning was dominant in Manchester.

Cotton brought relative affluence to these regions, with entire families sometimes working in the mills. Under the weak child labor laws then prevailing, children as young as ten would work at lower-paid, entry-level mill jobs like sweeping; in their teens, they could join women at the loom. Men took the higher-paying jobs, as engineers, for example. Owners demanded long hours to keep the capital-intensive factories running, but mill work paid better than farming. And workers were paid for their time rather than piece-rate.

Cotton brought prosperity not just to Manchester and Lancashire but throughout the area dubbed “Cottonopolis.” Cotton was truly a global trade. It was imported through Liverpool from the newly opened farming lands in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, which we covered earlier in a post about the panic of 1819. Cotton from the southern United States, with its long fibers, was considered by many to be best in the world and it was certainly in high demand; about three quarters of British cotton imports were from the United States. Once the cotton was woven into fabric, the cloth was exported throughout the world, often displacing inferior locally sourced textiles.

Cotton Diplomacy

The year 1861 was a good one for the cotton harvest, and cotton exports to Britain and elsewhere continued until about mid-December. In late 1861, hoping to force Britain and other European countries to ally themselves with the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War, some confederate states and cotton plantation owners announced an unofficial cotton “embargo” that sharply curtailed exports to these countries (“cotton diplomacy”). After stockpiled cotton was depleted in 1862, British mill owners addressed the shortage by reducing work hours and by seeking alternative cotton sources like India and Brazil. But by late 1862, mills started to close and by 1863, thousands were without work.

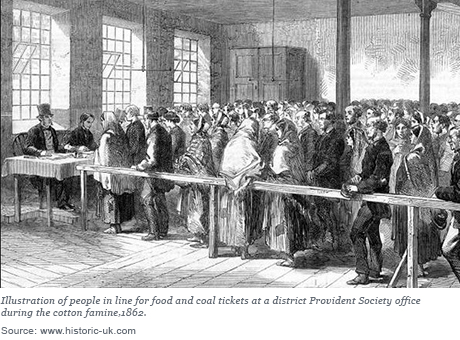

As the Northern blockade and cotton embargo continued, Southern leaders were sure that the economic losses incurred by Britain would force the country to enter the war in favor of the South. But despite the massive hardships brought on by the lack of cotton, Britain also depended on wheat from the northern U.S. states, and supplied the Union with the tools to make war: guns, ammunition, and ships. So rather than enter the war, Britain responded internally by raising huge sums for “relief,” and though not until 1864, enacted a Public Works Act to put thousands to work building parks and other public infrastructures.

One of the hardest hit towns was Stalybridge, where just a handful of the factories remained open. British support was strong and relief funds helped support the unemployed: “The scale of relief at Stalybridge had been unusually high, and some of the recipients were quite as well off under the relief committee as when engaged at their ordinary employments” (Watts, Facts of the Cotton Famine). But when the local relief committee decided to substitute tickets for relief money, riots and looting erupted: “The mob then passed on to the clothing stores of the relief committee, which were speedily broken upon, and the stock thrown into the street, where a regular scramble ensued, each one helping himself or herself to the best which they could get hold of” (Watts, Facts of the Cotton Famine).

The protests lasted only a few days and proved to be one of the few demonstrations against a largely effective and stoic British response to the crisis. By 1864, cotton supplies from Egypt, India, and Brazil had filled the gap, but not all of the mills survived. The largest, most advanced, and most efficient prospered while the smaller, less advanced, and less efficient mills never re-opened.

From Cotton to Currency

The paper or substrate used to make U.S. currency today depends on the same long, durable southern U.S. cotton fibers coveted by the textile mills in Lancashire. The substrate for our currency is a cotton-linen blend that gives it extra durability to withstand the banknote printing process in which ink is pressed into the paper. The extra durability of the cotton substrate also means extra durability in circulation. While the low-denomination notes of most nations that use a paper substrate last only a couple of years before they are removed from circulation owing to wear and tear, the U.S. one-dollar note, with its long cotton fibers and linen, lasts nearly six years in circulation. Some countries with a less durable cotton substrate or a harsh climate or circulating conditions have switched to a more durable but costlier polymer substrate. Meanwhile, other countries have replaced their low-denomination paper notes with a high-denomination coin. But because of the longer life of U.S. notes, there’s little reason to switch to a polymer substrate or to replace the one-dollar note with a one-dollar coin. But that’s our view. Tell us what you think.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

James Narron is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s Cash Product Office.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics