U.S. Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) currently control about 3,000 subsidiaries that provide community housing services—such as building low-income housing units, maintaining shelters, and providing housing services to the elderly and disabled. This aspect of U.S. BHC activity is intriguing because it departs from the traditional deposit-taking and loan-making operations typically associated with banks. But perhaps most importantly, the sheer number of these subsidiaries makes one think about the organizational complexity of U.S. BHCs. This is an issue that has generated much discussion in recent years. In this post we describe the emergence and growth of community housing subsidiaries and discuss to what extent they contribute to the complexity of their parent organizations.

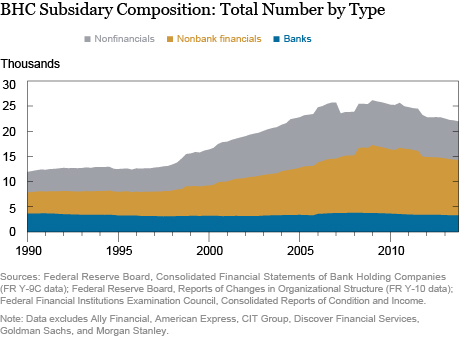

The overall number of subsidiaries controlled by BHCs has grown substantially over time, as evident in the chart below (for more on the evolution of BHCs see this previous post). An interesting feature of this organizational transformation is the existence of nonfinancial subsidiaries—entities engaged in activities outside the financial industry ranging from mining and oil extraction to construction and technology services. This industry pattern raises interesting questions regarding the business model of banking organizations. But it also raises potential concerns when it comes to issues of monitoring and regulation, resolution in the event of default, and possible transmission of shocks within a banking organization and across business activities.

Although BHCs control subsidiaries engaged in a large number of diverse nonfinancial industries, on closer observation, the emergence and growth of entities involved in community housing services (NAICS industry code 62422) is quite striking. As gathered from regulatory reports, the number of BHC subsidiaries classified as such has risen sharply from about 100 in 1990, to a peak of more than 3,000 in 2010. This growth is even starker in proportional terms (see the chart below). Community housing services subsidiaries grew from just about 3 percent of nonfinancial subsidiaries in 1990, to 39 percent by the end of 2013.

Regulatory Changes and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

Why these subsidiaries and why such growth? It turns out that changes in the bank regulatory environment are the main drivers for BHC involvement in this nonbanking activity, starting with the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). Passed in 1977, the CRA encourages banks to do more to “meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate.” In 1995, formerly opaque CRA regulations were revised to emphasize stricter performance-based measures. These new quantitative measures likely motivated banks to increase their investment in community housing. High CRA ratings are crucial for banks to receive FDIC insurance and to conduct activities like mergers and acquisitions.

Two other regulatory changes in the 1990s increased the interest in obtaining a high CRA rating. In 1994, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act allowed banks to expand across state borders. In 1999, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act allowed banks to merge or expand into activities such as investment banking and insurance. The advisory firm CohnReznick observes that the “demand for housing tax credit investment among the largest national banks has expanded significantly as the banks have grown through mergers and acquisitions” in order to satisfy the CRA.

Banks have found that one effective way to meet CRA requirements is through Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) investments. By 2012, the banking sector grew to represent approximately 85 percent of the roughly $10 billion in total LIHTC investments. Banks can invest in LIHTC directly by setting up limited liability partnerships or indirectly by investing money in LIHTC funds.

Large Banks Invest in Affordable Housing. . .

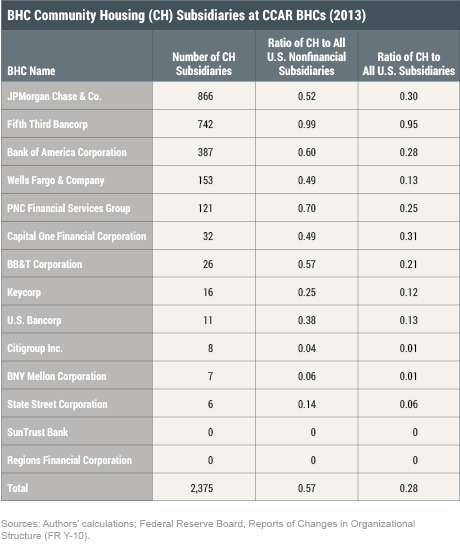

The demand for high CRA ratings, and thus LIHTC investments, is most evident in the largest banks. So let’s take a deeper look at the CCAR banks, which are the largest banks and subject to stress-testing (see the table below). The number of community housing subsidiaries varies widely from 866 for JPMorgan Chase to zero for Regions Financial and SunTrust Bank. In aggregate, 57 percent of all nonfinancial domestic subsidiaries owned by CCAR banks are community housing subsidiaries. But the ratio of these subsidiaries to all subsidiaries is quite heterogeneous. For example, 99 percent of Fifth Third Bancorp’s nonfinancial subsidiaries are in community housing services (third column). In contrast, some other banks do not own any of these subsidiaries because they rely on investing in LIHTC indirectly. In particular, Regions Financial reports that it uses LIHTC to satisfy CRA and SunTrust Bank says it invests hundreds of millions in LIHTC.

. . .But What Kind of Complexity Does It Add?

Whether community housing investments contribute to bank complexity is nuanced. These projects, involving equity ownership, are unusual compared to a bank’s traditional activity of making loans and may increase organizational complexity simply by increasing BHCs’ scope.

However, these investments don’t seem to complicate bank resolution. The balance sheet for these subsidiaries comprises assets and equity without complex secondary activities like securitization. Over time, as banks have merged, their community housing investments have moved with them relatively seamlessly. For example, in the mergers between Bank One and JPMorgan Chase, and between Wachovia and Wells Fargo, all community housing subsidiaries transferred to the acquiring bank. Furthermore, a secondary market exists to facilitate these transactions both between banks, and from banks to other types of corporations. The secondary market would make it easier to sell or value these subsidiaries in the event of a large bank resolution.

Moreover, though these subsidiaries are numerous, they tend to be small because BHCs usually set up a different subsidiary for each project. The limited liability structure caps losses for each entity and prevents losses from spreading to the rest of the BHC so the potential for contagion across the BHC is low. Thus, characterizing the complexity of BHCs requires understanding the types of subsidiaries that comprise the BHC and recognizing that some activities, like community housing services, add less complexity than other types of activities.

In conclusion, the number and share of BHC subsidiaries in the community housing services industry has exploded since the 1990s, in large part due to changes in the Community Reinvestment Act, banking regulation, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit. This evolution is interesting as we try to better understand banks’ business models. While community housing entities increase the scope of BHCs’ activity beyond traditional depository and lending activities, from the perspective of bank resolution and contagion these subsidiaries appear relatively innocuous.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Nicola Cetorelli is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rose Wang is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics