Editors’ note: The labels on the x-axis of the chart “Debt Payment Prioritization by Year” have been corrected. (March 7, 2017, 9:10 a.m.)

When faced with financial hardship, borrowers might choose to repay some debts while falling behind on others—potentially going into default. Such choices provide insight into consumers’ spending priorities and can help us better understand the condition of borrowers under financial distress. In this post, we examine how consumers prioritize their default choices. Do consumers under financial stress default on their credit cards first? Or are they more likely to default on their mortgage?

Using data from the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax (CCP), we can begin to answer these questions. We empirically model this situation as a kind of competition between types of debt, with each category of debt vying for the limited funds of a particular borrower. When this borrower has two forms of debt and only pays one, we predict which type of debt is most likely to be repaid. The repaid debt is designated the “winner” of our pseudo-competition. For example, if an individual pays his or her mortgage while defaulting on credit cards, we describe mortgage debt as the winner and credit card debt as the loser.

Once we consider this situation as a competition, we can see that predicting which debt is kept current is similar to predicting victory probabilities for a football game or a chess match—a task for which “Elo ratings” are used. An Elo rating reflects the strength of a player, or in this case debt, to win a head-to-head competition for payment priority. The higher the rating, the more likely the debt is to be kept in good standing.

We similarly estimate ratings for each type of debt using a symmetric logistic regression. Our approach can accommodate multiple kinds of debt simultaneously, giving a single rating for each category of debt by predicting the likelihood of payment relative to that for all other debt types. These ratings can also be calculated by year, state, or other subsets to see if this relative prioritization of debt changes over time or varies across individuals. In addition, this approach can control for loan characteristics, such as the balances due on the different categories of loans.

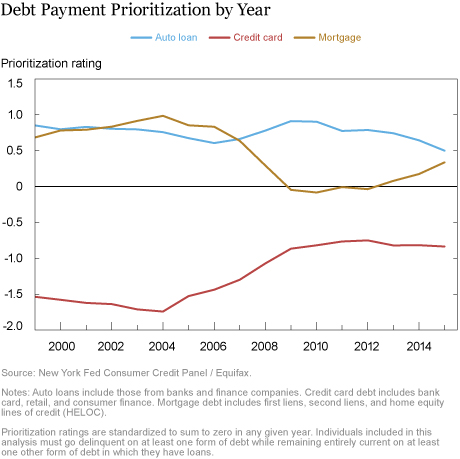

Looking at the ratings by year in the chart below, we can see that auto and mortgage debt are strongly prioritized over credit card debt. In the year 2000, for example, the ratings imply that auto and mortgage loans were respectively 10.8 and 10.6 times more likely to be paid in a competition with credit card debt. This makes intuitive sense, as individuals put their cars or homes at risk by defaulting on this collateralized type of loan. Generally borrowers have less to lose when defaulting on credit card bills.

Interestingly, we observe a sharp drop in the prioritization of mortgage debt relative to auto and credit card debt during the 2007–09 recession. Prior to the recession, individuals were about equally likely to prioritize auto loans as they were mortgage loans when given the choice, showing a slightly greater tendency to pay the latter. At the onset of the recession, this pecking order reverses, and auto loans become more than twice as likely to be paid when competing with mortgage loans.

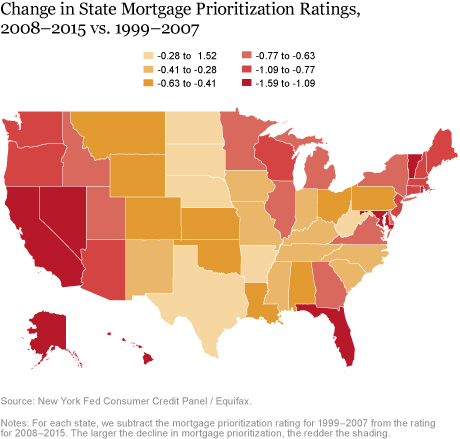

Calculating our prioritization ratings by state, we can observe which parts of the country experienced the largest drops in mortgage prioritization between the pre- and post-recession periods (1999–2007 and 2008–2015, respectively). In the map below, red shading indicates larger declines in mortgage prioritization. Mortgage prioritization fell across the United States in the aftermath of the recession, with California, Nevada, and Florida experiencing the largest drops in mortgage prioritization. These states also experienced large home price declines during the recession. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that individuals in states where house prices declined more had less equity in their homes and therefore less to lose by defaulting on their mortgage payments.

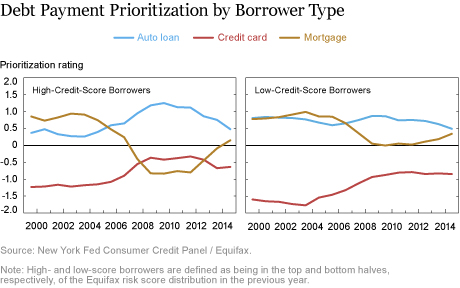

Borrower types offer another dimension for assessing debt prioritization patterns. The chart below compares the debt prioritization profiles of low- and high-credit-score individuals (defined as being in the bottom or top half of the Equifax risk-score distribution in the previous year). We see that while both sets of individuals experienced a decline in mortgage prioritization, the trend was particularly pronounced among borrowers with previously high credit scores. In fact, there was a period when high-credit-score individuals prioritized credit card debt over mortgage debt when choosing between the two!

These novel debt prioritization metrics allow us to characterize which debts individuals choose to keep in good standing. In particular, we are able to observe a large drop in the relative prioritization of mortgages in the post-recession period, a trend that is particularly pronounced in states that experienced a large decline in housing prices and among individuals with historically high credit scores. Our findings are consistent with strategic default motives—that is, borrowers choosing to cease payment on collateral whose value falls below the borrowed amount. However, additional analysis is needed to better identify precisely why people choose to prioritize one form of debt over another. In future work, we will look to further explain these patterns by considering the presence of nonrecourse laws and judicial foreclosures, the average time to foreclosure, home equity levels, and other such factors.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jacob Conway is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Plosser is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Jacob Conway and Matthew Plosser, “When Debts Compete, Which Wins?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), March 1, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/03/when-debts-compete-which-wins.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

T: Overall we think that there are arguments to be made either way regarding the relative prioritization of student loans. As you mention, the potential for wage garnishment and the inability to discharge student debt in bankruptcy would suggest that student loans might be highly prioritized. On the other hand, we would also expect student loan debt to be less prioritized due to its unsecured nature, in that one does not forfeit his or her house or car by not paying this debt. We’ve rerun our analysis including student debt, and find that student loans are consistently prioritized over credit card debt and below auto loans. Mortgage loans are prioritized over student debt outside of the recession period, with this relative prioritization reversed between 2008 and 2012. Comparing these categories to other debt types during this period, this reversal seems mainly due to a drop in mortgage prioritization, rather than an increase in the prioritization of student loans. Thanks for the interesting suggestion!

Sean: That’s a great point, and it’s something that we’ve thought about in our analysis. We do indeed have balances in our data, and can include the difference in balances as a control within our framework. When we do so, we generally find that conditional on the debt types, the debt category with the larger balance is less likely to be paid (vs. unpaid) during and immediately after the recession (2008-2012) but is more likely to be paid before and after this period. Including balances as controls has a very small effect on our debt prioritization metrics, but overall the general patterns described in this analysis are robust to the inclusion of this control.

Great post. The outstanding balance of student loan debt has now surpassed the amount of auto loan and credit card debt outstanding. Is there sufficient data to evaluate the prioritization of student loan payments relative to mortgage and other consumer debts? Does the non-dischargeability of student loans positively impact their priority?

I wonder if there is data on the debt balances for each type of debt. Might asymmetry among the debt types lower the probability of paying larger debts that one can no longer afford (such as a mortgage). Job losses created this scenario after 2008 for many. Autos are easier to pay and would additionally provide transportation to find work.

We’re glad you enjoyed the article. We agree that if some creditors are more willing to renegotiate this could influence which debts the individual chooses to pay. For this to explain the time-series pattern, the relative flexibility of lenders would need to vary over time (which is certainly possible but would be a more involved story). Your question gets at the deeper question of why debt categories are prioritized differently, which we think is an interesting area for further research.

I enjoyed reading your well researched article. I was wondering if the willingness of the creditors (by industry) to work with delinquent borrowers had any affect on the results? Perhaps auto lenders were more willing to find an amicable resolution when low-credit score borrowers went delinquent than mortgage lenders?

We’re glad that you enjoyed the post! We agree that there remains a link between paying other debts and keeping one’s credit card account open, and that universal default and the details of the CARD act could contribute to this link and to the pecking order of debt more generally. To isolate the effects of these policies, we would need some variation in exposure to the policies. For example, if issuers were more likely to enforce these policies in certain geographic areas or with certain consumer groups, we could compare debt prioritization behavior across these groups. In addition to the policies you mention, debt repayment is also linked by other factors. These include the presence of nonrecourse laws and judicial foreclosure, both of which vary by state. Our colleagues here at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York do an excellent job of analyzing some of these linkages (http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jmcb.12304/full), and we look to build on this analysis using our framework of debt prioritization. We’ll add universal default practices to our list of policies to examine in more detail.

Great post. Reminds me of a working paper from the Philadelphia Fed. In the 90s a concept called universal default became popular with credit card companies, whereby accounts could be priced up to the penalty APR if the customer’s credit report showed they were in default on another debt. Anecdotally, some issuers were more likely to use the practice than others, even if it was provisioned for in the CMA. The CARD Act prevents issuers from assessing the penalty APR in these situations, but apparently does not restrict them from calling in the balance (placing the account in default and closing it). Bottom line is, there may still be a link between paying your other debts and keeping your credit card account open, provided that consumers are aware of the potential of this occurring, and issuers are enforcing that part of their agreements. Would you be able to use your framework to measure the effects of these policies on debt repayment patterns?