Regulatory reforms since the financial crisis have sought to make the financial system safer and severe financial crises less likely. But by limiting the ability of regulated institutions to increase their balance sheet size, reforms—such as the Dodd-Frank Act in the United States and the Basel Committee’s Basel III bank regulations internationally—might reduce the total intermediation capacity of the financial system during normal times. Decreases in intermediation capacity may then lead to decreased liquidity in markets in which the regulated institutions intermediate significant trading activity. While recent commentary by market participants claims that this is indeed the case—a Wall Street Journal article [subscription required] notes that “three-quarters of institutional bond investors say that liquidity provided by bond dealers has declined in the past year…”—empirical studies have struggled to find evidence supporting this narrative. In this post, we summarize the findings of our recent article in the Journal of Monetary Economics that addresses the apparent disconnect between the market-participant commentary and the empirical evidence by focusing on the relationship between bond-level liquidity and financial institutions’ balance sheet constraints.

Investigating the Impact of Regulations on Market Liquidity Provision

We use a supervisory version of the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) to construct trade-based measures of corporate bond market liquidity and to capture dealers’ trading activity. The data include detailed trade information from securities brokers and dealers that are members of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA)—including the full name of the reporting FINRA member and the uncapped size of the trade. The revealed identities enable us to match FINRA members to their parent bank holding company (BHC).

Using the transactions data, for each bond we compute a summary liquidity measure based on common corporate bond liquidity metrics and measures of constraints faced by traders. The constraint measures are constructed in two stages: first, we calculate institution-level constraints using the balance sheet information of the BHCs, which is collected through the Federal Reserve Y-9C reports. We then construct bond-level measures of constraints as the total-volume-weighted average of constraints of institutions that trade in the bond. Thus, if constrained institutions intermediate a greater volume of transactions in a bond, the bond-level measure of constraints is higher as well. This approach allows us to quantify, in the cross-section, the extent to which a tightening of constraints faced by market participants leads to a decline in bond liquidity.

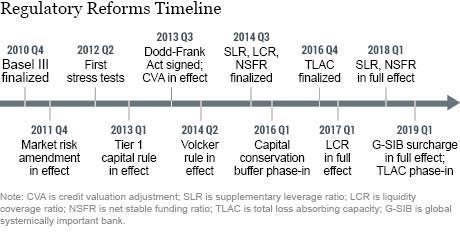

Event studies are a popular approach to evaluate the impact of regulation. However, as the chart below shows, many regulations were proposed, finalized, and implemented around the same time, making the attribution of changes in liquidity to any one regulation challenging. Instead, we focus our analysis on four subperiods:

- Pre-crisis (January 1, 2005 – December 31, 2006)

- Crisis (January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009)

- Rule writing (January 1, 2010 – December 31, 2013)

- Rule implementation (January 1, 2014 – March 5, 2016)

We study whether the relationship between balance sheet constraints and bond liquidity evolves over these subperiods.

BHC-Bond-Level Analysis Reveals Changes in Liquidity

We first document that there is a relationship between institutional constraints and bond liquidity. Using the full history of transactions, we find that bonds traded by more levered and systemic institutions (those with higher leverage, a higher ratio of securities bought under repurchase agreements to assets, and higher financial vulnerability), and bonds traded by institutions more akin to investment banks (BHCs with smaller ratio of risk-weighted-assets to assets, smaller allocation to loans, and higher trading revenues) are less liquid. These results hold across bonds with different credit ratings, issued by companies in different industries, with different issuance sizes, and with different prior levels of liquidity.

The relationship between bond liquidity and institution-level constraints does, however, change significantly over time. We find that, prior to the crisis, bonds traded by institutions with higher leverage, higher return on assets, lower risk-weighted assets, lower reliance on repo funding, and lower vulnerability (as measured by Adrian and Brunnermeier 2016 CoVaR) were more liquid. During the rule implementation period (starting in January 2014), these relationships reverse—bonds traded by institutions with lower leverage, higher risk-weighted assets, more reliance on repo funding and lower return on assets were more liquid. That is, the relationship between bond liquidity and dealer constraints that we see in the full sample is primarily driven by that same relationship in the post-crisis period.

What then causes the relationship between bond market liquidity and dealer constraints to change over time? We show that, after the crisis, institutions with higher leverage and higher trading revenues have lower overall transaction volume while, prior to the crisis these same institutions had higher overall trading volumes. This pattern reversal is consistent with more stringent leverage regulation and greater regulation of investment banks reducing institutions’ ability to provide liquidity to the market overall.

More importantly, we find that, during the rule implementation period, institutions with higher repo funding, higher trading revenue, higher vulnerability, and lower allocation to loans are less able to intermediate customer trades—where we measure the ability to intermediate trades as the ratio between customer and interdealer trading volume. That is, institutions more affected by post-crisis regulation are less able to intermediate customer trades.

Finally, we show that—although constraints faced by buyers in the market generally have a similar impact on bond liquidity to the constraints faced by sellers—bonds bought by institutions with higher vulnerability during the rule implementation period are more liquid, whereas bonds sold by institutions with higher vulnerability are less liquid. This result is consistent with regulation aimed at reducing the risk of systemic institutions, such as the Basel III accord, affecting the willingness of these institutions to hold corporate bond positions.

In Sum

A number of recent empirical papers have examined post-crisis changes in corporate bond market liquidity and have come to mixed conclusions on the impact of regulatory reforms. While Bessembinder et al. 2016 and Bao, O’Hara, and Zhou 2016 find decreased liquidity during idiosyncratic stress events, Trebbi and Xiao 2015 and Adrian et al. 2016 conclude that aggregate bond market liquidity remains largely unaffected by post-crisis regulation. These papers, however, rely on indirect measures of the effect of regulation on corporate bond market participants.

Instead, we link directly the trading behavior of market participants to their balance sheet constraints. We find that post-crisis regulation has had an adverse impact on bond-level liquidity. To evaluate the full welfare impact of regulation, however, one needs to also consider the effects of regulatory reforms during periods of market stress and on the likelihood of such stress arising. As noted at the outset, regulatory reform has sought to promote the stability of the financial system so that episodes of market stress and illiquidity are both less likely and less severe.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Tobias Adrian is the financial counsellor and director of the Monetary and Capital Markets Department of the International Monetary Fund.

Nina Boyarchenko is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Nina Boyarchenko is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Or Shachar is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Or Shachar is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Tobias Adrian, Nina Boyarchenko, and Or Shachar, “Dealer Balance Sheets and Corporate Bond Liquidity Provision,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), May 24, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/05/dealer-balance-sheets-and-corporate-bond-liquidity-provision.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics