Workplace benefits—such as parental leave, sick leave, and flexible work arrangements—are increasingly being recognized as important determinants of differences in labor supply behavior, education and occupation choice, inequality in wages, and gender disparities in labor market outcomes. Researchers have argued that the failure of the United States to keep pace in providing more generous workplace benefits accounts for 29 percent of the decline in the nation’s labor force participation rate for women relative to that of other high-income countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In this post, using novel data from a special module of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) fielded in May 2015 and May 2016, we document the labor market prevalence of workplace benefits, analyze workers’ preferences for them, and discuss their impact on labor supply.

Access to Benefits

The results from the SCE—released through the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data—demonstrate that 75 percent of employed respondents have access to parental leave, 80 percent have access to sick leave, and 42 percent have access to flexible work arrangements. These findings are comparable to the results from the American Time Use Survey. Moreover, the SCE results show that the prevalence of benefits differs significantly for full-time and part-time workers. While 86 percent of full-time workers have access to parental leave, only 59 percent of part-time workers have such access. Part of this heterogeneity might stem from the specifics of the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which guarantees twelve weeks of unpaid leave for adoption, birth, and illness to workers covered by the law. Part-time workers who worked less than 1,250 hours in the last twelve months are not covered.

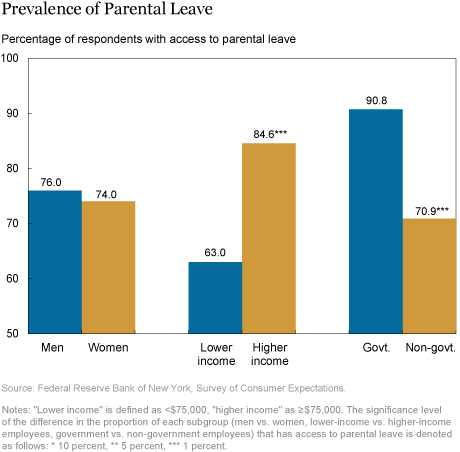

The prevalence of parental leave also differs across other subgroups in the sample (see chart below). Although there is no significant difference in access between men and women, there is substantial heterogeneity based on income level and economic sector. Sick leave and flexible work arrangements (flex work) display similar patterns.

When we look at the average duration of a benefit among those who have access to that benefit, we observe the same trends as in the prevalence margin, except for the length of flex work hours per week. Even though the prevalence of flex work is greater for workers with higher income or government jobs, non-government employees have longer flex work hours per week.

These results indicate that access to workplace benefits is not universal. Moreover, even when workers have access to these benefits, there is no guarantee of complete take-up. To shed light on this phenomenon, the SCE asks currently employed respondents why they might choose to forgo parental or medical leave. Fifty-two percent of the respondents cite financial constraints, making this the most common reason for not taking leave, while 39 percent of respondents point to career concerns. A higher proportion of women than men, and a higher proportion of lower-income workers than higher-income workers, cite these reasons.

The Willingness to Pay for Benefits

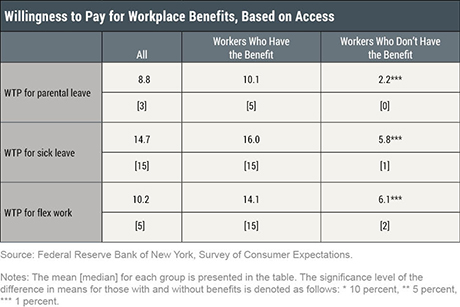

In addition to asking questions about the prevalence of workplace benefits, the survey elicits information about respondents’ willingness to pay for such benefits. We interpret willingness to pay (WTP) as a measure of individuals’ preferences for particular benefits. Individuals who already have access to a given benefit in their current job are asked,

Suppose you were offered a job today that is identical to your current job except that it did not provide [the benefit]. By what percentage would the salary on the new job have to be higher, if at all, for you to accept this job?

Individuals who don’t have access to that benefit in their current job are asked,

Suppose you were offered a job today that is identical to your current job except that it also provided [the benefit]. What percentage of your current salary would you be willing to give up to accept this job?

The table below presents means and medians for the willingness to pay for each workplace benefit. The average WTPs are sizable, with the average WTP for sick leave being the highest. More importantly, for all three workplace benefits, the WTP of workers who already have access to the respective benefit is significantly higher than that of workers who do not already have access. While differences in how questions are phrased may influence these patterns, the patterns—if real—are consistent with a conclusion that workers sort into jobs based on their preferences for workplace non-wage benefits.

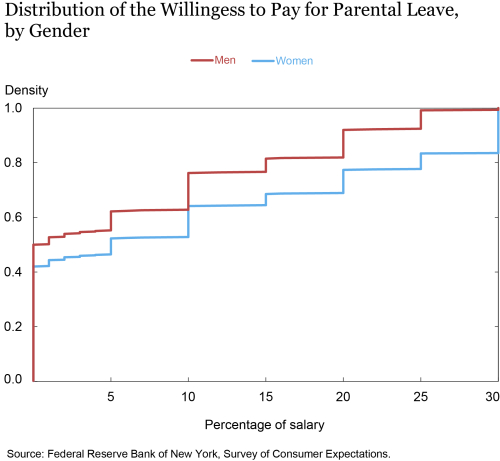

There is substantial heterogeneity in the valuation of these workplace benefits. The next chart shows the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of parental leave WTP as a percentage of current salary, broken out by gender. The CDF indicates the proportion of the respondents that value parental leave at or below the corresponding percentage of current salary. Applying this interpretation, we observe that at any given cost (in terms of percentage of current salary), a greater proportion of women than of men are willing to pay more. Women, on average, value parental leave at 10.4 percent of their salaries, compared with 6.8 percent for males.

Workplace Benefits and Labor Market Behavior

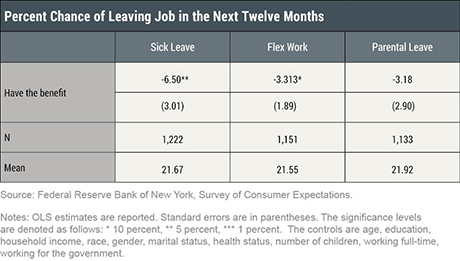

As a first step toward understanding the relationship between workplace benefits and labor supply behavior, we examine whether access to a given workplace benefit is related to respondents’ decisions to remain in, or leave, their jobs. The table below shows the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates from the regression of the percent chance of leaving the current job in the next twelve months—a measure of job satisfaction—on having access to a given benefit. We find that even after controlling for worker characteristics and other job characteristics, having access to a workplace benefit is associated with a significantly—economically and statistically—lower reported likelihood of leaving the job. For example, having sick leave available reduces the chance of the respondent leaving the job by 6.5 percentage points.

Conclusion

In this post, we use novel data from the SCE to document heterogeneity in the prevalence of and demand for workplace benefits. In addition, we find evidence that the access to benefits is associated with a higher expected likelihood of remaining in a job. Of note, our analysis shows that women, on average, have a higher willingness to pay for workplace benefits. This result provides some support for the hypothesis that the failure of the United States to keep pace in providing more generous workplace benefits may help explain why the nation’s labor force participation rate for women has stalled and fallen behind that of many other high-income OECD countries. In future work, we plan to investigate more broadly how preferences for workplace benefits affect labor supply and contribute to observed gender differences.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Gizem Kosar is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Basit Zafar is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Gizem Kosar, Wilbert van der Klaauw, and Basit Zafar, “Valuing Workplace Benefits,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), June 2, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/06/valuing-workplace-benefits.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics