The size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet increased greatly between 2009 and 2014 owing to large-scale asset purchases. The balance sheet has stayed at a high level since then through the ongoing reinvestment of principal repayments on securities that the Fed holds. When the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decides to reduce the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, it is expected to do so by gradually reducing the pace of reinvestments, as outlined in the June 2017 addendum to the FOMC’s Policy Normalization Principles and Plans. How do asset purchases increase the size of the Fed’s balance sheet? And how would reducing reinvestments reduce the size of the balance sheet? In this post, we answer these questions by describing the mechanics of the Fed’s balance sheet. In our next post, we will describe the balance sheet mechanics with respect to agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

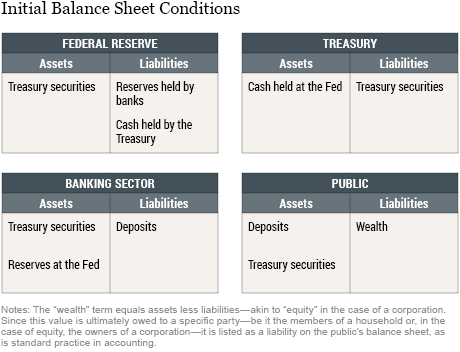

We start by describing simplified balance sheets for the Fed, the Treasury, the banking sector, and the nonbank public. The exhibit below omits a number of items that we would expect to find on these balance sheets, to enable us to focus on the elements that are essential for understanding the mechanics related to the Fed’s actions.

- On the Fed’s balance sheet, we focus on Treasury securities on the asset side, and deposits held by various types of account holders, which are liabilities of the Fed, on the liabilities side. (These deposits include reserves in the case of banks or cash balances in the case of the Treasury.)

- The Treasury, in contrast, holds cash balances in its “checking account” at the Fed (the Treasury General Account, or TGA) as assets, and issues Treasury securities as its liabilities.

- The banking sector holds both Treasury securities and reserves as assets and offers bank deposits to the public.

- The public can hold Treasury securities and bank deposits as assets. In contrast to the banking sector and the Treasury, the public cannot hold balances in a Fed account. Eligibility to open and maintain a Fed account is limited to depository institutions (which we call the banking sector), the Treasury, and certain other financial institutions such as government-sponsored enterprises, designated financial market utilities, and foreign official institutions. Wealth corresponds to the difference between the public’s assets and its liabilities.

Asset Purchases

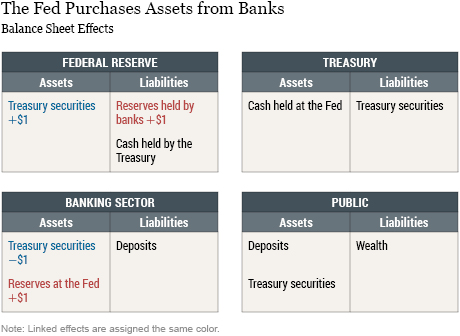

With this setup, we can illustrate how the Fed’s asset purchases increase its balance sheet. The exhibit below describes the effect of Fed purchases of Treasury securities from the banking sector. The Fed purchases Treasury securities by issuing more reserves (it does this by electronically crediting reserves to the selling bank’s Fed account). So, for each dollar of securities purchased, both the Fed’s assets and its liabilities increase by a dollar. When banks sell the Treasury securities, their Treasury security assets decrease and their reserves increase by exactly the same amount.

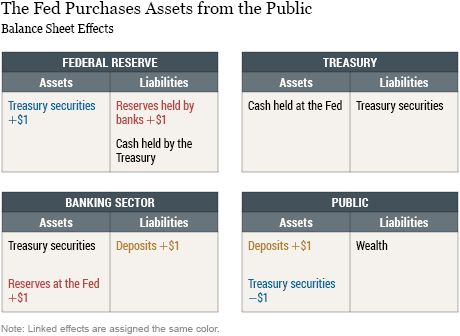

When the Fed purchases assets from the public, as illustrated in the next exhibit, the mechanics are different because the public cannot hold reserves issued by the Fed. Instead, the banking sector holds the reserves and the public holds more deposits at banks. Three transactions occur simultaneously:

- The Fed purchases the securities with reserves, just as in the case above.

- Because the public cannot hold reserves directly, banks hold the reserves on behalf of the public and credit the deposit account of the seller of securities with the proceeds from the sale.

- When the public sells the Treasury securities, its holdings of Treasury securities decrease and its deposits at banks increase by exactly the same amount.

From the Fed’s perspective, it doesn’t matter who is selling the securities; the size of its balance sheet increases by the same amount in either case. By contrast, the size of the banking sector’s balance sheet depends on who sells the assets. If banks sell the assets, the size of the banking sector’s balance sheet is unchanged, although its composition is different. However, if the assets are sold by the nonbank public, the banking sector’s balance sheet will increase by the amount of assets purchased, at least initially. (Banks could subsequently offset this initial increase by engaging in transactions that shift their assets and liabilities to nonbank financial institutions if they wanted to limit growth of their balance sheets, but this is not shown in our exhibits. For example, banks could sell some of their assets to the public. Carpenter, Demiralp, Ihrig, and Klee show that most of the assets purchased by the Fed during its large-scale asset purchases were from nonbanks. An important implication is that the Fed determines the level of reserves, not the banks, as is shown in more detail in a paper by Todd Keister and James McAndrews.)

The Fed’s Reinvestment Policy

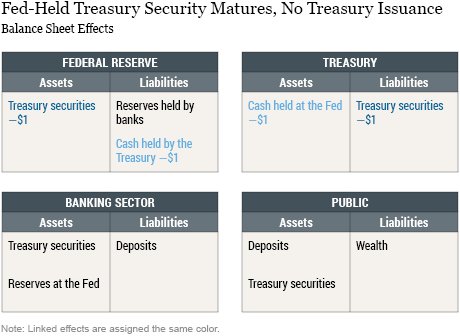

To build some intuition regarding Fed reinvestment, we first consider the case where Treasury securities held by the Fed mature, the Fed does not reinvest the proceeds of the maturing securities, and the Treasury does not issue new securities. In this case, depicted in the next exhibit, the Treasury pays the Fed by “transferring” cash from the TGA to the Fed as the securities mature. The Fed holds fewer assets but also has fewer liabilities, so the size of its balance sheet decreases.

For the remainder of this post, we will assume that the Treasury issues new securities to replace maturing ones and to maintain its outstanding debt at a constant level. To make things simple, we assume that new securities are issued at the same time as old securities mature. That may not always be the case in practice.

If the Fed reinvests the proceeds of its maturing Treasury securities into newly issued securities, then the size of its balance sheet does not change. For every dollar of maturing securities, the Fed purchases a dollar of new securities, keeping its Treasury holdings constant (more detail is available on the New York Fed’s website). This is the rollover policy the Fed has been pursuing for the last few years. (When the Fed replaces maturing holdings with securities issued at Treasury auctions, the Fed’s purchases are treated as add-ons to the Treasury’s announced auction sizes.)

We can now consider the case where the Fed does not reinvest the proceeds from maturing securities, to see how this will reduce the size of its balance sheet. For simplicity we assume that the Fed ceases reinvestments completely, but the mechanics are the same, scaled down proportionally, if it reinvests only a fraction of the maturing securities.

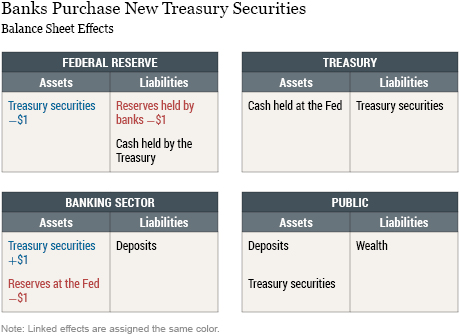

If the Treasury issues new securities as old ones mature and the Fed does not buy new securities, then someone else must do so. The exhibit below illustrates the case where banks buy the new securities. Two transactions happen simultaneously:

- As in the previous exhibit, the Treasury repays the Fed for the maturing securities, which reduces the TGA’s balances and the Treasury securities held by the Fed by the same amount.

- Banks purchase the new securities issued by the Treasury. This step results in a transfer of balances from the banking sector to the Treasury, offset by a transfer of securities to the banking sector.

At the end of this process, the size of Fed’s balance sheet has decreased, the Treasury’s balance sheet is unchanged, and the size of the balance sheet of the banking sector is the same but its composition is different.

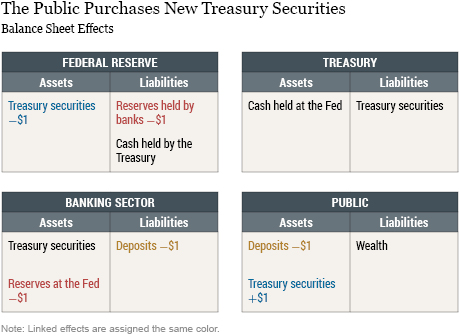

What if the nonbank public purchases the newly issued Treasury securities instead? This case is illustrated in the last exhibit. Here, three different transactions occur simultaneously:

- As before, the Treasury repays the Fed for the maturing security.

- The public buys securities from the Treasury, which appears as an increase in TGA balances at the Fed.

- Since the nonbank public cannot hold reserves, deposits held at banks decrease as the public uses the value it holds in deposits at banks to purchase the securities.

This is essentially the reverse of the third exhibit above. As noted earlier, the banks and the public could take subsequent actions to modify their assets and liabilities. The ultimate effects on their balance sheets could work out in many different ways depending on their preferences.

In this blog post, we have described the mechanics of asset purchases and the effects of the FOMC’s reinvestment policies, focusing on simplified balance sheets for the Fed, the Treasury, the banking sector, and the nonbank public. This approach helps illustrate how asset purchases increase the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and how ceasing reinvestments will decrease it. We have also shown that what happens to the banking sector’s balance sheet depends on whether the public or the banking sector buys or sells Treasury securities. In our next post, we explore a similar set of issues in the case of agency MBS.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Deborah Leonard is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Markets Group.

Antoine Martin is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Antoine Martin is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Simon M. Potter is an executive vice president and head of the Bank’s Markets Group.

Simon M. Potter is an executive vice president and head of the Bank’s Markets Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Deborah Leonard, Antoine Martin, and Simon M. Potter, “How the Fed Changes the Size of Its Balance Sheet,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), July 10, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/07/how-the-fed-changes-the-size-of-its-balance-sheet.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your comments. In light of the comments we have received about this post, we decided to write a new post that provides a closer look at the Fed’s balance sheet accounting. This post can be found at the following URL: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/08/a-closer-look-at-the-feds-balance-sheet-accounting.html .

Joel: Thank you for your comment. Congress prohibits the Federal Reserve to purchase securities directly from the Treasury (this staff report provides more details: https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr684.pdf.) The securities obtained as part of the large scale asset purchases were bought on the open market. Information about the Federal Reserve’s rollover policy can be found on the New York Fed’s Website at https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/treasury-rollover-faq.html.

Mr. Leikind asked about the Fed itself not about reserve banks. He is asking why the Fed itself cannot coordinate with Treasury whereby both parties agree to an accounting offset, essentially erasing their positions. The answer given to Mr. Elliott supplies the reason as you indicate that the Fed views principal payment made by Treasury as not subject to the remittance rules. The Fed needs to cite the legal authority for this position. In plain terms, the Fed has created money/reserves out of the air, as authorized by law, and used it to purchase a Treasury security. Your legal position is that the Treasury (i.e., the public) must borrow anew to pay the principal amount at maturity even though the amounts were made up by Fed officials initially. Accounting offset is the sane thing to do if remittance is required. It may be the morally correct thing to do regardless of your current opinions on the law.

Hello, following up on an aspect of an earlier question, is the Federal Reserve required to purchase bonds directly from the Treasury if the Treasury directs the Fed to purchase them, rather than sell the bonds to private dealers who then resell them to the Fed? I recall that in the 1920’s and 1930’s that the Treasury could simply direct the Fed to purchase remaining bonds that failed to sell at auction. Thanks!

Douglas: Thank you for your comment. You note, correctly, that all the Fed’s income, net of costs, is remitted to the Treasury. Payments of principal, however, do not generate distributable income (in contrast to interest payments). As we show in the post, when the Fed holds a Treasury security to maturity and does not roll it over into new securities, two things happen to the Fed’s balance sheet: 1) The securities disappear from the asset side of its balance sheet, and 2) the amount of cash held by the Treasury in its Fed account decreases by the same amount on the liability side of its balance sheet. In other words, instead of paying the Fed by exchanging the maturing security with another asset (as would be the case with a rollover), the Treasury “pays” the Fed by reducing its claim on the Fed. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) recently described how it plans to reduce the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings in an addendum to its Policy Normalization Principles and Plans (which can be could at this link: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20170614c.htm). Principal repayments that are not reinvested will run down the Fed’s securities holdings and reduce the size of its balance sheet through dynamics like those we illustrate in this blog post. The FOMC notes, as you do, that reducing the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings will result in a declining supply of reserve balances. But the FOMC has not specified its desired future level of reserve balances, saying only that it anticipates reducing the quantity of reserves to a level appreciably below that seen in recent years but larger than before the crisis. You can find updated staff projections for the future size of the Fed’s domestic securities portfolio—based on a range of market expectations for the long-run level of reserve balances and other Fed liabilities taken from recent surveys—on the New York Fed’s website at https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/annual_reports.html.

Bernard: Thanks you for your question. Even though they serve the public, the Federal Reserve Banks, which ultimately hold the Treasury securities, are not part of the federal government. As such, their consolidated balance sheet is distinct from the Treasury’s balance sheet. The Fed does not have the ability to retire Treasury debt, and the Treasury makes principal and interest payments to the Fed as it does to any other holder of Treasury securities. Moreover, the Fed wishes to hold Treasury securities to pursue its policy goals. For example, the Fed purchased longer-term Treasury securities to put downward pressure on interest rates, and has continued to hold them in order to help maintain accommodative financial conditions. Having a stock of securities to sell, as was done through the Maturity Extension Program in 2011 and 2012, is another way the Fed can carry out its monetary policy objectives. In addition, securities the Fed holds can be lent out under securities lending arrangements with primary dealers. These lending transactions provide a temporary source of securities to the financing market to promote the smooth clearing of Treasury securities.

Hello, Could you please explain if Treasury repayment of maturing securities to the Fed would be subject to the Fed policy of remittance to the Treasury as interest payments are? It appears from this explanation that it is not. Has the Fed formally described its intended treatment of principal repayments if they are not reinvested in security purchases? It appears that under this explanation, to return the fed balance sheet to pre crisis levels, and assuming that the outstanding federal debt remains constant, the fed is anticipating that bank reserves will necessarily shrink by a commensurate amount, upwards of 3 trillion dollars? Thanks for any further clarification you could provide.

When the Fed purchases a Treasury security from a bank, why doesn’t it mark the security Paid In Full, and send it down to the Treasury Department to correct the Treasury’s liability account? Why does the Fed keep the security on its books, collect interest from the Treasury which it sends back to the Treasury at the end of the year, and collect the principal when the security matures? The member of the public, or the bank, that loaned Uncle Sam money has been paid back.