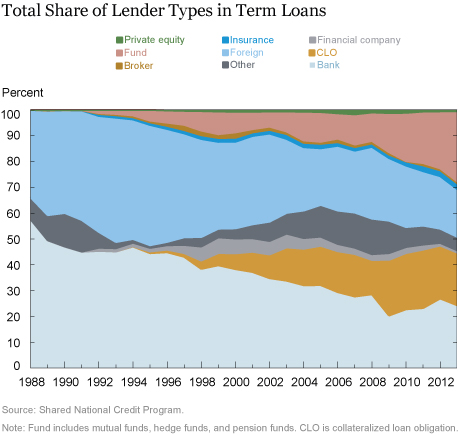

Over the last two decades, the U.S. secondary loan market has evolved from a relatively sleepy market dominated by banks and insurance companies that trade only occasionally to a more active market comprising a diversified set of institutional investors, including collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), loan mutual funds, hedge funds, pension funds, brokers, and private equity firms. This shift resulted from the growing presence of these investors in the syndicates of corporate loans, as shown in the chart below. In 1991 the average term loan had just two different types of investors; by 2013 that number had grown to five.

The arrival of these new investors likely boosted secondary loan market activity because increased investor diversity indicates differences in business models and thus a higher likelihood that an investor will need to trade in order to meet some goals. And while banks and insurance companies tend to follow a buy-and-hold investment strategy, the new investors trade more actively, for a variety of reasons: to manage credit risk, meet liquidity needs, pursue minimum return targets, or boost equity return through leverage. Greater investor diversity also likely gives rise to divergent opinions about the value of a loan and to “trigger trading.” According to the Loan Syndications and Trading Association (LSTA), trading volume in the secondary loan market surged from $8 billion in 1991 to $517 billion in 2013, a compound annual growth rate of about 20 percent. In this post, we discuss how the growing presence of a more diversified set of institutional nonbank investors has affected the liquidity of loans in the secondary market.

Measuring Liquidity and Diversity

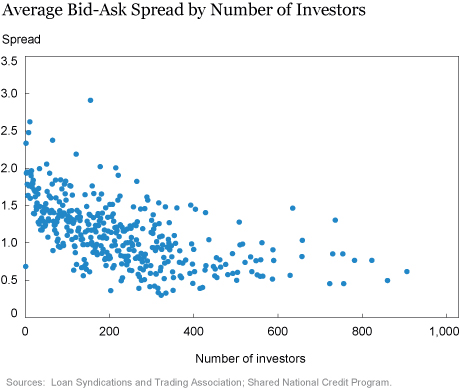

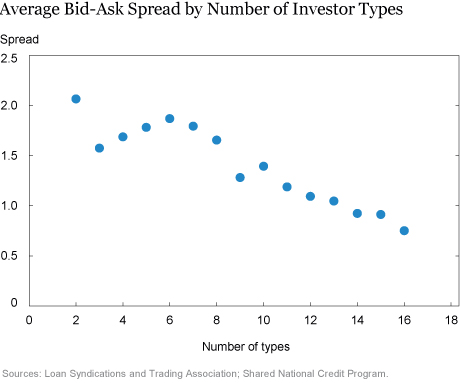

We measure loan liquidity by the mean quoted bid-ask spread over the year—that is, the difference between a loan dealer’s ask and bid price quotes at a given time. Theories posit that the bid-ask spread reflects three costs faced by dealers (order processing costs, inventory costs, and information costs), all of which should decline as the liquidity of the loan or security increases. There is supporting evidence for these assertions. We measure the bid-ask spread over the year because our information on loan investors is as of year-end.

We measure investor diversity by either the number of investors holding the loan or the number of institutional types of investors—banks, CLOs, or hedge funds, for example—in the syndicate. We expect both measures to be associated with increased trading and higher liquidity, particularly the latter since liquidity measures actual diversity of types whereas increased trading could just reflect a larger number of investors of the same type.

We merge data on loan bid-ask spreads from the mark-to-market loan pricing services of the LSTA/Thomson Reuters Loan Pricing Corporation over the 1998-2012 time period with information on the investors for each of these loans from the Shared National Credit Program. This process left us with a sample of 2,415 term loans from 400 corporations, for a total of 4,964 term-loan-year observations.

Consistent with our expectation, bid-ask spreads fall, suggesting increased liquidity, as the number of loan investors increases and the average number of investor types increases (see the two charts below). This insight builds on univariate comparisons, but the loan’s bid-ask spread will likely be affected by a wider variety of factors. While these findings ignore other potential determinants of liquidity, our recent working paper shows that they hold even after we control for loan- and borrower-specific factors and time and loan arranger fixed effects, among other things. Further, and importantly, reverse causality does not seem to explain our findings because loan liquidity does not explain our (future) measures of investor diversity.

Not All Diversity Equals Liquidity

While our evidence points to a strong relationship between investor diversity and loan liquidity, not all investors increase liquidity. On close inspection, we find that investor types that are believed to follow a buy-and-hold strategy—such as banks and insurance companies—have an adverse effect on loan liquidity. In contrast, investor types that are believed to be active traders—namely, private equity firms and funds—have a positive effect on loan liquidity.

Our findings confirm the thesis that it takes a difference of opinions to have a horse race. The arrival of other investors, besides banks and insurance companies, in the syndicate loan market has increased loan trading and improved market liquidity and efficiency. These findings also suggest that the need to cater to active trading investors will likely incentivize loan originators to standardize loans [subscription required], moving a step away from one of the cornerstones of bank lending—offering customized funding to borrowers.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

João A.C. Santos is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group

Pei Shao is an associate professor at the University of Lethbridge.

How to cite this blog post:

João A.C. Santos and Pei Shao, “Investor Diversity and Liquidity in the Secondary Loan Market,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August 9, 2017, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/08/investor-diversity-and-liquidity-in-the-secondary-loan-market.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics