Editor’s note: The original version of this post misstated the share of the population that is unbanked for several states. The table, interactive chart, and related text have been corrected. These changes did not alter our conclusion that across states, the share of the population that is unbanked is not positively correlated with the share living in banking deserts.

Unbanked households are often imagined to live in urban neighborhoods devoid of banks, but is that really the case? Our map of U.S. banking deserts reveals that most are not in urban areas, where financial exclusion may be endemic, but in actual deserts—largely in the sparsely populated, rural West. Across states, we find that the share of the population in a banking desert is unrelated to the share that is unbanked. If distance from a bank is not what causes financial exclusion, then motivating banks to locate closer to the unbanked may not promote financial inclusion.

The Banking Desert Map

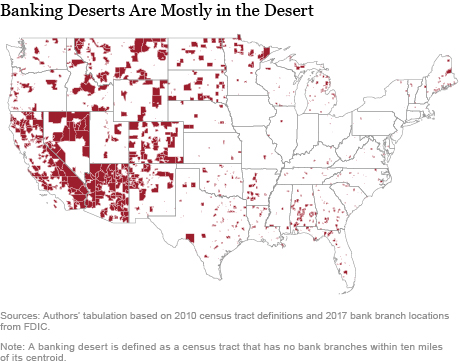

As in our previous post, we define a banking desert as a census tract (roughly a neighborhood) that has no bank branches within it or within ten miles of its center (technically, its centroid).

Below we map all 75,057 tracts covered in the 2010 census, with the 1,214 banking desert tracts shaded red. Commentary on banking deserts often paints a picture of neglected urban landscapes and communities abandoned by banks. In fact, most banking deserts are in very sparsely populated areas in the West; most of Arizona, northern Nevada, and southwestern California, which are actual deserts (or semi-arid regions), are also banking deserts. Mississippi, Arkansas, and Maine have a few deserts, but there are almost none in the Northeast or the Midwest. Overall, just 23 percent of banking deserts are in Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs), with the rest in rural areas. New York City, the largest MSA in the country, has no banking deserts, nor do its neighboring MSAs, Boston and Philadelphia.

The relative paucity of urban deserts supports the finding in our earlier post that residents of majority-minority census tracts, which tend to be urban, are less likely to live in a banking desert than residents of other tracts. Although that result seems sensible (since urban areas are better able to support a bank branch), it might depend partly on how banking deserts are defined (see this study).

Are Desert Dwellers Financially Excluded?

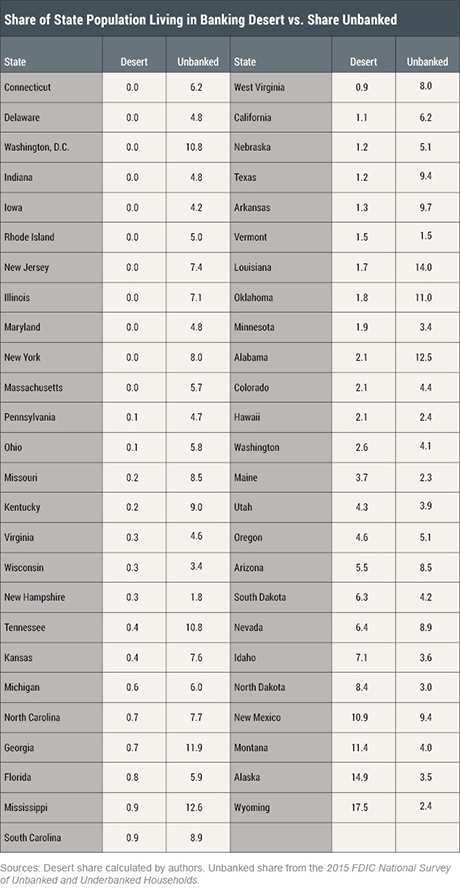

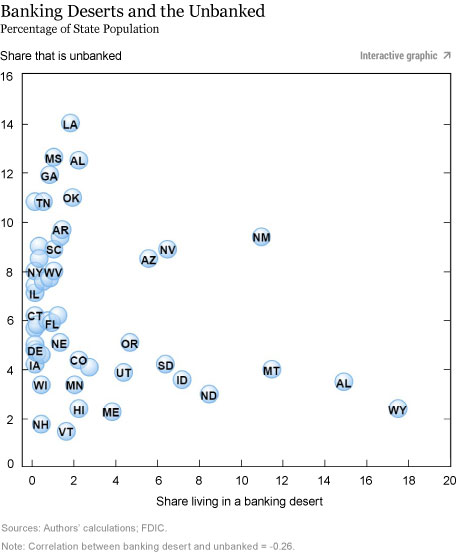

The latest (2015) FDIC survey on financial inclusion estimated that 7 percent of U.S. households—nine million—were unbanked (no bank or credit union account). The table below reports the share of each state’s population that is unbanked, according to the FDIC survey, along with the share living in a banking desert. The two measures do not necessarily move together; the share of Washington, D.C., residents living in a banking desert is zero, yet its unbanked share is almost 11 percent. Likewise, Louisiana has the highest unbanked share in the United States, almost one in seven residents, but the share of Louisianans living in a banking desert is very small. Across all states, the correlation between the two (-0.26) is not statistically different from zero at the 95 percent confidence level.

A Barren Concept?

“Banking desert” is an evocative term, but our findings make us wonder if it’s a distraction. Most banking deserts are literally in deserts, where few people live, and states with a higher share of bank desert dwellers don’t have more unbanked households.

On the policy front, physical distance from a bank seems not to be what keeps the unbanked away, and so motivating or compelling banks to open branches near the unbanked may not reduce their numbers. In fact, in the FDIC’s 2015 survey, only 2 percent of unbanked respondents cited “inconvenient location” as the main reason why they did not have a bank account. Far more important reasons were “not enough money to keep in account,” “don’t trust banks,” and “account fees too high.” Those issues merit more attention than banking deserts.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Maxim L. Pinkovskiy is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davy Perlman is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Davy Perlman is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Donald P. Morgan, Maxim L. Pinkovskiy, and Davy Perlman, “The ‘Banking Desert’ Mirage,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), January 10, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/01/the-banking-desert-mirage.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

kd: Thanks for your interest. “Banked” means a person or household has a checking account regardless of how they access the account, so someone with an account but without remote access (via phone or internet) would still be considered banked. In answer to your other question, the 2015 FDIC survey we cited shows that 36.9 percent of banked households in metropolitan areas (principal city) accessed their account primarily online versus 27.4 percent in non-metro areas (Appendix Table B.8, p. 82 ). The survey may also have separate numbers for metro versus rural. Here’s the link: https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2015/2015appendix.pdf

Does unbanked include those that do not have access to remote bank accounts? Is there a statistical difference between the use of remote accounts in rural v. urban areas?

JAFD: Thanks for your comment. Our use of a ten-mile cutoff in defining a banking desert follows this paper: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2010.00343.x/pdf Though the ten-mile metric seems standard, we see your point and we’re already considering experimenting with a lower cutoff. While lowering the cutoff could alter our finding of essentially no correlation between the share of state population that is unbanked and the share of banking desert “dwellers,” it wouldn’t change the fact from the FDICs Financial Exclusion Survey that “inconvenient location” ranks far below other reasons (high fees, inadequate savings, and mistrust of banks) as reasons unbanked household cite for not having a checking account. That finding, as much as our own (on the location of banking deserts mostly in deserts and rural areas and the zero correlation just mentioned), informs our conclusion that the notion of “banking deserts” and emphasis on proximity, may distract attention from those other, evidently more important, reasons why households decide to go without a checking account. We also agree that local knowledge and soft information matter for credit availability, which is a topic that we discussed in our previous post: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/03/banking-deserts-branch-closings-and-soft-information.html Thanks again for the comment and reading our post!

This is a very unintelligent post. You are saying there is ‘no problem’ because you have defined the problem away ‘No bank branch within ten miles’ _automatically_ excludes almost all the US except literal deserts. But an urban neighborhood ‘nine miles from downtown’ where a business owner cannot make a deposit or pick up change without locking down and taking a drive, where no branch manager can tell HQ about local entrepreneurs, where kids grow up thinking of ‘finance’ as check-cashing and payday loan shops and ‘banks’ as things used by the rich folk somewhere else… Mr. Morgan, Mr. Perlman, and Mr. Pinkovskiy – Please Open Your Eyes And Look Around You !