Household debt balances continued their upward trend in the second quarter, with increases in mortgage, auto, and credit card balances, according to the latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit from the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data. Student loans were roughly flat, a typical seasonal pattern in the second quarter. The Quarterly Report contains summaries of the types of information that is covered in credit reports, sourced from the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel (CCP). The CCP is based on anonymized Equifax credit reports and is the source for the analysis provided in this post, which focuses on an area that until recently has received little attention: collections accounts.

Third-party collections are quite prevalent; in the past ten years alone, more than 40 percent of individuals with a credit report had a collections account at some point. And collections accounts can reflect an extraordinarily wide array of financial commitments—although they certainly do reflect traditional consumer debt balances that have defaulted and been sold to third-party collections firms, there are also other types of unpaid debts—medical debt collections, rent payments, traffic tickets, and even unreturned library books. In the first paper that looked comprehensively at credit reports, Avery, Bostic, Calem, and Canner reported that in 2003, 52 percent of unpaid collections accounts were associated with medical debts and 23 percent were associated with unpaid utility accounts, while only 6 percent were associated with defaulted accounts sold by financial institutions.

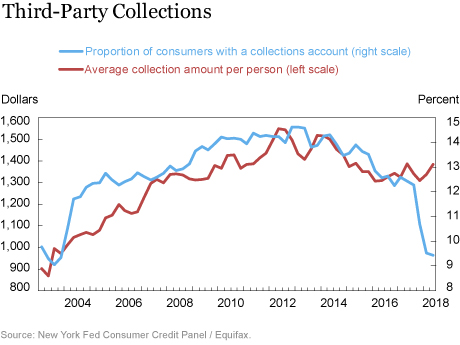

The chart below, which is from our Quarterly Report, shows that collections accounts became more prevalent between 2008 and 2012 as Americans went through the financial hardships presented by the Great Recession. But there has since been a declining trend in the blue line which shows the percent of consumers (that is, individuals with an Equifax credit report) with a collections account on their credit report declined from over 14 percent to 12 percent between 2013 and 2017. But in the fourth quarter of 2017, that share suddenly dropped to only 9 percent.

This sudden and sharp decline was anticipated by those watching the credit bureaus and had been discussed by the press in advance of the change. The downturn was a result of a change in the required reporting practices that impacted collections accounts specifically, known as the National Consumer Assistance Plan (NCAP), which rolled into effect during the second half of 2017. The plan has many components, including: (1) a requirement for more frequent, detailed, and accurate reporting of collections accounts, including reflecting when those accounts have been paid; (2) a prohibition against reporting debts that did not arise from an agreement to pay, or from, medical collections less than 180 days old; (3) the removal of collections accounts that did not arise from a contract or agreement to pay; and (4) permission to report any account only when there is sufficient information to link the account with an individual’s credit files (requiring a name, address, and some other personally identifying information such as a Social Security number or date of birth).

Impact on Collections Accounts Reporting

Between June 2017 and June 2018—the time period during which the NCAP was implemented—the number of individuals with a collections account on their credit report fell from 33 million down to 25 million. The number of collections accounts reported also dropped substantially, from more than 66 million collections accounts at the end of the second quarter of 2017 to about 47 million appearing on credit reports in the second quarter of 2018. The aggregate balances reported on collections accounts also declined, by about $11 billion.

Who Benefitted?

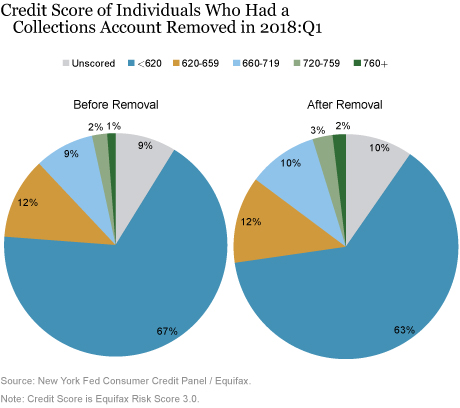

Here, we examine the individuals who had a decline in the number of collections accounts reported on their credit reports in the first quarter of 2018. As may be expected, the majority of these individuals had relatively low credit scores to begin with. Nearly 9 percent had no scores at all—mostly collections—only credit records too thin to actually be scored. And nearly 80 percent of the individuals in this group had credit scores below 660 before the drop in accounts, as shown in the chart below. Only a very small share had very high scores. Overall, these individuals had higher delinquency rates on other debts besides their collections accounts—in fact, 33 percent of them had some kind of delinquency in their credit accounts, compared to only 8 percent of everyone else.

A Mixed Impact on Credit Scores

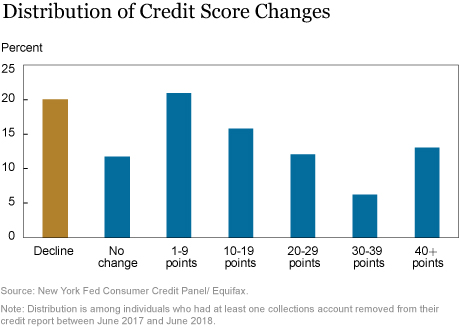

We find that the impact on individuals of removing at least one collections account from a credit report was relatively small on average. Because the vast majority of people in this group had very low credit scores and flawed credit histories to begin with, the effect of these collections accounts being removed was modest overall, with an 11 point increase in the Equifax Risk Score on average. However, there is considerable variation in observed credit score changes. The distribution of score changes is shown in the chart below:

Score Down:

About 20 percent of individuals saw a decline in their credit score, very likely reflecting a worsening in other negative aspects of their credit history during the same quarter. This means that the credit score change we report is not entirely attributable to the removal of collections but would incorporate other possible contemporaneous changes.

Score Up, a Little:

The most common impact of the NCAP was no change or a small credit score increase—an average 11-point increase during the quarter the collections accounts were removed; just about half saw an increase of less than 20 points.

Score Up, a Lot!:

However, a nontrivial 18 percent of affected individuals saw their credit scores increase by more than 30 points. Those who saw the largest boost to their scores were generally those with initially very low credit scores. For example, those who saw a 40 or more point increase in their score began with a 529 on average, and ended with an average of 588.

Only 20 percent of the individuals with scores under 620 saw enough of an increase to lift them above the 620 mark. For many of them, they had charged-off balances on their credit reports (so their credit scores were already on an upward trajectory as the derogatory information aged). But, given that their score remains deeply subprime even after the boost, it’s likely that the collections accounts were not the only thing holding down their score and contributing much to their ability to get credit. These individuals also may have benefitted from the other changes to credit reporting that would have resulted in the removal of tax liens and judgments from the public record portion of their credit report, thereby also providing a boost—although our data suggest this was a very small share.

A Cleanup, Not a Purge

All in all, the changes in credit reporting prompted by the National Consumer Assistance Plan have resulted in an $11 billion reduction in the collections accounts balances being reported on credit reports. A total of 8 million people had collections accounts completely removed from their credit report. However, collections accounts do indeed align with other negative events and the cleanup of collections accounts had the largest impact on the borrowers with the lowest scores. These borrowers will certainly benefit in the long run from the cleanup of their credit reports, since higher scores are associated with better access to credit, to the job market, and even to the rental housing market. But the immediate impact of the removal of collections will be muted if the beneficiary’s credit record continues to be tarnished with other negative information.

We also think that in the longer-term there may be a rebound in collections account reporting because creditors will likely begin collecting the newly required personally identifying information as they adjust to this reporting change. We will continue to monitor the changes in this area.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Andrew F. Haughwout is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donghoon Lee is an officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Joelle Scally is a senior data strategist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Andrew F. Haughwout, Donghoon Lee, Joelle Scally, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Just Released: Cleaning Up Collections,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), August 14, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/08/just-released-cleaning-up-collections.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Shane: Thank you for your comment. The Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) provides a few resources that may help. Repairing a credit score takes time, and the CFPB does list best credit practices (pay bills on time, maintain low credit utilization, etc.), warning signs of fraudulent credit repair services, and even templates for writing letters to the credit bureaus. Some consumers go through a credit repair company, but these companies may mislead their customers. In September 2016, the CFPB issued a consumer advisory on how credit repair services were charging excessive (and sometimes illegal) fees. A list of credit counseling agencies approved by the federal government to provide counseling to individuals before they can file for bankruptcy can be found here: https://www.justice.gov/ust/list-credit-counseling-agencies-approved-pursuant-11-usc-111. Consumers also may dispute information with Experian, Transunion, and Equifax directly on the credit bureaus’ websites. The CFPB provides free templates for disputing incorrect credit information with either a credit company or a bank and offers step-by-step guides on how to fill out such letters. For an example, see this link: https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/092016_cfpb__CreditReportingSampleLetter.pdf Many large cities also offer vetted, lower cost credit counseling services. New York City, for example, offers these through the Department of Consumer Affairs Office of Financial Empowerment.

Rebecca: Thank you very much for your comment. We hope to be able to look further into the considerations that you identify.

I am glad to see this kind of work being done. I won’t even go into the litany of problems this credit reporting system has created. I think the existence of the this research affirms the above statement. I think our system is more damaging than you might expect. I believe people get a bad enough score (sometimes on accident or maybe not even of their own doing) and they just run away from it for as long as they can. It stops a person from being a productive part of our society and economy. It destroys morale, trust in government, faith in themselves, etc. What BAFFLES me is that there isn’t a simple way to fix your issues. Aside from paying debts (or at least creating easily understood payment plans) I don’t know one person who knows how, when, or where to find a professional who can facilitate a quick repair to the score. Shouldn’t their be a safe and confidential way to create a plan to pay, take some educational courses, maybe even pay a fine and get the score reset or reset with a one year probationary tag? I am in finance, studied economics, as well as own several business. I see this every day. I think this alone would transform our economy into a productive one after a few years of implementation.

I read this blog with great interest, particularly as it relates to the significant reduction in collection accounts on Equifax credit reports. The post indicates that reported accounts have declined most dramatically since the 4th quarter of 2017, and attributes this significant drop primarily to “required reporting practices via the National Consumer Assistance Plan (NCAP) which went into effect in late 2017.” It is important to draw your attention to what may be a more significant reason for this decline: the deletion of account tradelines by some debt buyers and collections agencies who are using the “pay for deletion” as a tool to entice customers to repay their debt. This practice began in late 2016 and appears to make consumers with bad debt better off by allowing for increased access to credit. Rather, it prevents banks from identifying vulnerable customers, causing them to provide credit at levels that are inappropriate for their financial situation, eventually worsening their credit situation and credit terms for everyone. Even more concerning, widespread adoption of this practice, which has happened, leads to the deterioration of credit report accuracy, potentially creating systematic credit risk similar to that which contributed to the credit crisis we experienced during the Great Recession. Further, it runs afoul of the standards and guidelines (Metro2) that require entities that furnish data to credit bureaus to do so in a manner that ensures data accuracy, integrity and completeness.