Halting a nearly decade-long downward trend, the U.S. labor force participation rate (LFPR) has flattened since 2016, fluctuating within a narrow range a little below 63 percent. What role has the economy played in this change and what can we expect for the future? In this post, we investigate the extent to which the recent flattening of participation can be attributed to the simultaneous robust improvement in the labor market. We also assess the future path of participation in the medium run should labor market conditions improve further.

Labor Force Participation: A Simple Framework

Several factors help to explain changes in overall participation. First, the aging of the U.S. population—which we think of as an increasing share of the older age groups—is a force toward a lower LFPR, since older people tend to have lower participation. Second, changes in the participation rate of a specific age group, either owing to a particular trend or in response to an increasingly tight labor market, will also alter the aggregate participation rate. Our goal is to use this simple framework to both (1) decompose the realized LFPR path into different components and (2) to use the same framework for hypothetical scenarios going forward.

To that end, our first task is to characterize how participation rates respond to labor market conditions—that is, to understand the relationship between tightness and the labor force participation rate of different age groups. We use two measures to capture labor market tightness: the job‑finding rate and the job-loss risk.

Both measures should be expected to affect labor force participation rates. When jobs are scarce, nonparticipants may hold off on searching for a job, and unemployed people who are not successful in securing a job may end their job search and exit the labor force. An increase in the rate at which unemployed workers find jobs may thus stimulate participation. Using the Current Population Survey (CPS), we measure the job‑finding rate as the fraction of the unemployed in a given month that have a job the next month. Since January 2016, this rate has increased a full 4 percentage points, from 24 percent to 28 percent.

Similarly, a lower job-loss risk might push some nonparticipants to start looking for jobs since job security is an important determinant of job search decisions. In addition, the decline in flows into unemployment would also result in lower exits from the labor force because unemployed people are more likely to leave the labor force than the employed. Taking these two factors together, a decline in job-loss risk might increase participation. We measure this risk as the share of employed individuals in a given month who are out of work and looking for a job in the next month. Since January 2016, the job-loss rate has remained relatively stable, fluctuating between 1.0 and 1.2 percent.

Measuring the Effect of Labor Market Conditions on Participation

In order to sort out the effects of labor market conditions on participation, we use the CPS to construct state-level participation, job-finding, and job‑loss rates for four age groups (16-24, 25-54, 55-64, and 65+) for the period 1994-2017 at the annual frequency. We then regress the participation rates for each group on the job-finding and job-loss rates, controlling for aggregate time trends as well as permanent differences across states. Our regression results indicate that a one percentage point increase in the job‑finding rate is associated with a 0.16 percentage point increase in the aggregate participation rate relative to its trend (View our detailed results.) The results also indicate that participation responds with some lag. However, changes in job-loss risk appear to have no statistically significant effect on participation.

Investigating the responses by age shows that young people’s participation decisions are the most sensitive to changing labor market conditions. This result is consistent with the observation that young people with little or no work experience have an easier time entering the workforce when the labor market is performing well. Conversely, young people may delay entry into the workforce, perhaps by obtaining additional schooling, when the labor market is doing poorly.

We investigated differences by gender as well, but found similar sensitivities for men and women, with men’s participation being slightly more cyclical than that of women.

Quantifying the Role of Labor Market Conditions

We use the estimated sensitivities of labor force participation to the job‑finding rate to quantify the role of changing labor market conditions over the past two years. We begin by looking at aging. Starting in January 2016, we compute the path of participation under the following assumptions for the period until April 2018:

- The age structure of the U.S. population evolves as in the data;

- The participation rate of each age group continues its trend over the period 2010-16; and

- The job-finding rate remains at its January 2016 level.

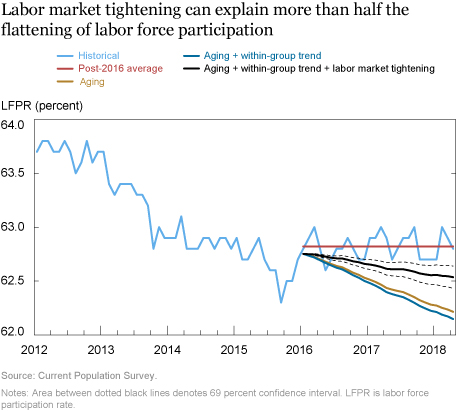

The gold line in the chart below shows that, absent any changes to the participation rates of individual age groups, the aging of the population would have lowered the participation rate by 0.6 percentage points over the two-year period. The dark blue line shows that the trends in participation within each age group had little effect on overall participation.

How big is the effect of the robust tightening of the U.S. labor market? To answer this question, we use the estimated effects from the first table linked above and calculate the path of participation implied by the changes in the job-finding rate over the period 2016-18. We ignore changes in the job-loss rate given the lack of evidence on its effect on participation. The solid black line shows the effect of labor market tightening in addition to the impact of the aging population. Our results imply that the tightening of labor market conditions explains about 60 percent of the flattening of the participation rate.

Where is Labor Force Participation Headed?

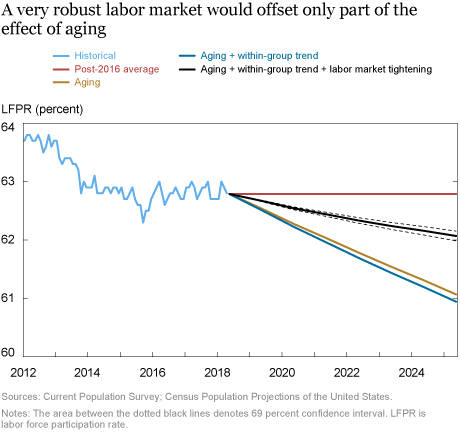

Our findings highlight a nontrivial role played by the labor market in shaping aggregate labor force participation. An immediate question involves the future of participation. The aging of the population is expected to continue exerting downward pressure. If the labor market tightens further, could it undo this trend and push participation up? We use the same framework to address this question, focusing on a five-year-ahead scenario. In particular, we assume that demographic trends over the next five years will continue as predicted by the U.S. Census Bureau, and that the within-age-group participation trends of the past five years will continue into the future. For this exercise, we also assume that labor market conditions will continue to tighten at the same rate as in the past eight years—namely, the job-finding rate will increase by 1.6 percentage points per year over the next five years.

As a side note, we can determine the unemployment rate that would be consistent with such a scenario for the job-finding rate, assuming that the separation rate (both voluntary and involuntary exits) remains at its current level and using the same equilibrium approach as in “The Bathtub Model of Unemployment.” The assumed hypothetical path for the job-finding rate is consistent with an unemployment rate reaching 3.7 percent by 2020 and 3.4 percent by 2023. This scenario is perhaps somewhat optimistic; therefore, we can treat the path of the participation rate predicted by this scenario as an upper bound.

The results of this exercise are depicted in the chart below. We find that—in this scenario—an aging population would continue to lower participation by more than one full percentage point over the next five years (see the dark blue line in the chart). As the solid black line indicates, even a strong labor market is unlikely to completely offset this declining trend: at most, the further tightening of the labor market would only undo about 60 percent of the effect of aging, and would add about one percentage point to the LFPR.

Our results thus indicate that even a very robust labor market is unlikely to undo all the effects of an aging population, and that a lower labor force participation rate seems likely to persist in the future.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Rene Chalom is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Fatih Karahan is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Laura Pilossoph is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Rene Chalom, Fatih Karahan, Laura Pilossoph, and Giorgio Topa, “Whither Labor Force Participation?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), September 10, 2018, http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/09/whither-labor-force-participation.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for the insightful analysis and clear presentation. Would this analysis benefit from adding a layer of (expected and/or stressed) net immigration changes over the next several years?