The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the federal corporate profit tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. Adding in state profit taxes, the overall U.S. tax rate went from 39 percent, one of the highest rates in the world, to 26 percent, about the average rate abroad. The implications of the new law for U.S. competitiveness depend on how these statutory tax rates compare with the actual rates faced by U.S. and foreign companies. To address this question, this post presents new evidence on tax payments as a share of profits, as well as analytical measures of tax impacts on profitability. We find that the U.S. effective tax rate was already below the average rate abroad prior to enactment of the TCJA, and that it is now well below the rate in most countries.

Statutory vs. Effective Tax Rates

Prior to enactment of the TCJA, the U.S. statutory tax rate on corporate profits was the highest among the world’s twenty largest economies (see chart below). Corporate tax rate data compiled by the accounting firm KPMG show the United States as having the fourth highest tax rate out of more than 170 economies. Many observers argued that the high U.S. tax rate was a hindrance to economic performance, discouraging investment in productivity-enhancing activities and providing an incentive for U.S. firms to shift operations to lower-tax jurisdictions.

The TCJA goes a long way toward aligning U.S. statutory corporate tax rates with rates abroad. With the federal rate now at 21 percent, the overall U.S. tax rate stands at 26 percent, about the weighted-average rate for large foreign economies.

But were the actual tax rates faced by U.S. corporations prior to the new law really as high as a focus on statutory rates would imply?

Business taxes raise the rate of return needed for a project to go forward. The marginal effective tax rate (METR) measures the size of this effect: how much higher a project’s return must be to break even. A break-even project has an expected payoff just high enough to cover the required return to investors, physical depreciation costs, and any resulting tax liabilities. The theoretical underpinnings of the METR were formalized in the 1960s by Hall and Jorgenson, and the concept remains a staple of the corporate tax literature.

A numerical example will help in interpreting our results. Suppose investors require a risk-adjusted real return on a project of 5 percent, but tax costs boost the needed return to 7 percent. Then the METR for the project is (7 – 5)/7 = 28.6 percent.

Two aspects of a country’s tax code are important in METR calculations: the tax rate and depreciation schedules. Deductions for depreciation allow firms to exclude some of a project’s payoff from taxable income. In fact, given immediate deductibility (expensing), the payoff on a break-even project is entirely shielded from taxation. Short of that, the effective tax rate can be dramatically lowered if depreciation deductions can be taken early in a project’s life rather than spread out over many years. Our analysis relies on detailed depreciation schedules assembled by the Oxford Centre for Business Taxation.

METRs also depend on a number of economic parameters, including investors’ required real rate of return, corporate borrowing rates, the inflation rate, physical depreciation costs, and the mix between equity and fixed-income financing. Our parameter choices are outlined in the notes to the table below, and are similar to those in earlier cross-country studies of corporate tax rates. In addition, aggregate METRs depend on the breakdown of new investment spending between machinery and structures, since the two are subject to different physical and tax depreciation rates. We treat new investment projects as involving a 65 percent outlay on machinery and a 35 percent outlay on structures, consistent with the composition of tangible fixed investment spending in the United States over the past decade. Results for machinery and structures are presented separately below.

We find that the U.S. marginal effective tax rate was already somewhat below rates in other large economies prior to enactment of the TCJA. As can be seen in the table, the estimated METR for the United States was just 10.8 percent versus an average of 13.8 percent for the remaining members of the global top twenty economies. With the enactment of the TCJA, the estimated METR for the United States is just 3.6 percent, the second lowest in this group.

The low aggregate METR for the United States reflects exceptionally favorable tax treatment for machinery investments. Prior to enactment of the TCJA, 50 percent of new machinery expenditures could be written off immediately and most of the rest could be deducted from income over the first three years of a project. The result was an estimated METR for machinery of just 4.9 percent. Under the TCJA, 100 percent of most machinery investments can be expensed. In essence, the U.S. tax code now subsidizes machinery investment, with the METR at -3.8 percent.

However, expensing for machinery expenditures is slated to be phased out in stages beginning in 2023. By 2027, the U.S. METR for machinery should stand at 14.6 percent, still below most other large economies.

U.S. tax treatment for business structures is much less favorable. Depreciation deductions for most such investments are spread out on a straight-line basis over thirty-nine years, sharply reducing their present value. This left the U.S. METR for structures at 21.6 percent prior to enactment of the TCJA, the highest rate among the twenty largest economies. The rate currently stands at 17.3 percent, still among the highest in this group. The METR for structures is set to rise somewhat over the next decade, as TCJA provisions limiting interest deductions increasingly take hold.

Tax Payments as a Share of Economic Profits

Marginal effective tax rates provide a useful analytical benchmark for assessing how the tax code affects the returns to new capital spending. Ultimately, however, what matters to international investors is the share of investment returns actually collected as taxes.

Previous attempts to address this question have generally relied on the net income line item from corporate financial statements as a measure of investment returns. This measure is subject to two important limitations. First, accounting standards differ widely across countries, making it difficult to measure returns on a consistent basis. Second, net income typically includes equity income and capital gains from ownership stakes in other companies, raising the possibility of double-counting and muddying the implications for returns to firms’ own business activities.

These difficulties can be sidestepped by turning to consistently defined national accounts data on economic as opposed to accounting profits. The United States is one of the few major economies that reports corporate profits as part of its regular GDP release, but profits for most other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries can be derived from the components of value added. Economic profits are equal to value added from current production less compensation of employees, depreciation costs, net interest and rent payments, and taxes on production net of subsidies. A new working paper by Tørsløv, Wier, and Zucman is one of the few international studies that also relies on a national accounts measure of profits.

Given data limitations, the results here are for the nonfinancial corporate sector, which represents about 85 percent of the overall corporate sector in most OECD countries. The non-OECD countries in our original sample do not report the relevant data.

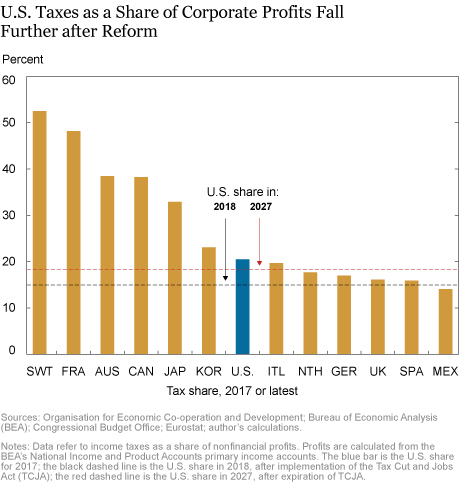

We find that U.S. corporate tax payments were relatively low prior to enactment of the TCJA. As can be seen in the chart below, taxes amounted to 20.5 percent of nonfinancial profits in 2017 (the blue bar) versus an average of almost 28 percent for the rest of the economies in our sample (gold bars). The United States was in fact the median country: Six countries had higher profit tax shares, often substantially higher, while six countries had somewhat lower tax shares.

To gauge the likely effects of the TCJA, we rely on Congressional Budget Office projections of corporate profits and federal profit tax revenues over the next decade. (These projections include estimates of what tax revenues would have been absent the new law.) We then adjust these projections to take account of the typical weight of the nonfinancial sector in total corporate profits and profit tax payments.

These adjusted projections imply that tax payments will come to 15.2 percent of U.S. nonfinancial profits in 2018 (the black dashed line), one of the lowest shares in our sample. (Data for the first half suggest that the U.S. tax share might fall even more sharply in 2018, perhaps to as low as 13 percent.) As temporary provisions of the TCJA expire, however, tax payments will begin to rise again. Our projections place the share at 18.6 percent in 2027 (red dashed line), not quite 2 percentage points below its 2017 value.

Conclusion

This post finds that effective profit tax rates in the United States were already relatively low prior to enactment of the TCJA, and that they are now even lower. The years ahead will tell whether this reduction provides a meaningful boost to business investment spending.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

Matthew Higgins is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Matthew Higgins is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Matthew Higgins, “Tax Reform and U.S. Effective Profit Taxes: From Low to Lower,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), October 22, 2018, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/10/tax-reform-and-us-effective-profit-taxes-from-low-to-lower.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics