In the wake of the 2007-09 financial crisis, a wide range of new regulations have been introduced to improve the stability of the banking system. But has the banking system become safer since the crisis? In this post, we provide a new perspective on this question by employing four analytical models, each measuring a different aspect of banking system vulnerability, to evaluate how system stability has evolved over the past decade.

Vulnerability Measures

We study four measures of banking system vulnerability based on models developed by Federal Reserve Bank of New York staff or adapted from academic research.

- Capital vulnerability: This index measures how well capitalized banks are projected to be after a severe macroeconomic shock. The measure is constructed using the CLASS model, a top-down stress testing model developed by New York Fed staff. Using the CLASS model, we project the regulatory capital ratio of each large banking organization under a macroeconomic scenario equivalent to the 2008 financial crisis. The vulnerability index measures the aggregate amount of capital (in dollars) that would be needed under that scenario to bring each banking firm’s capital ratio up to at least 10 percent.

- Fire sale vulnerability: This index measures the magnitude of systemic spillover losses among banks caused by asset fire sales under hypothetical stress scenarios, expressed as a fraction of system capital. In this New York Fed staff report, we show that an individual bank’s contribution to the index predicts its contribution to systemic risk five years in advance.

- Liquidity stress ratio: This ratio captures the liquidity mismatch between a bank’s assets and liabilities during a liquidity stress scenario. It is defined as the ratio of expected cash outflows in times of stress to the size of the bank’s portfolio of liquid assets. If the ratio is high, this means that there may be insufficient liquid assets that can be liquidated to meet expected outflows in stressful conditions.

- Run vulnerability: This measure gauges banks’ vulnerability to runs, taking into account both liquidity and solvency. It combines a theoretical framework with projections of stress deterioration in bank capital from the CLASS model. An individual bank’s run vulnerability is the critical fraction of unstable funding that the bank needs to retain to prevent insolvency.

Trends in Vulnerability

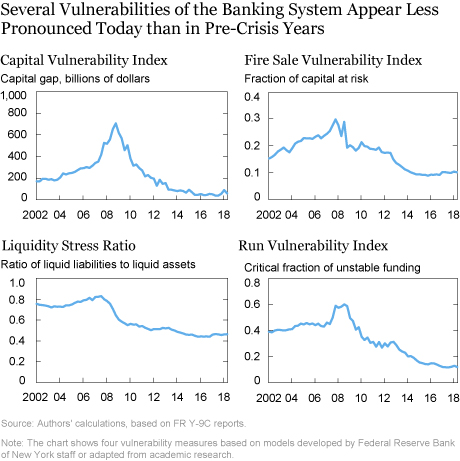

The next chart shows how banking system vulnerability has evolved according to the four measures. Although the pattern differs somewhat for each measure, they all show rising vulnerability in the years leading up to the financial crisis and a considerably lower level of vulnerability today.

The capital vulnerability index panel of the chart shows that the capital “gap” increased markedly in the period leading up to the financial crisis, peaking at around $700 billion at the end of 2008. Since that time the index has declined sharply, reflecting recapitalization by the U.S. banking industry. The index is now significantly below pre-crisis levels, despite continued growth in the asset base of U.S. banks.

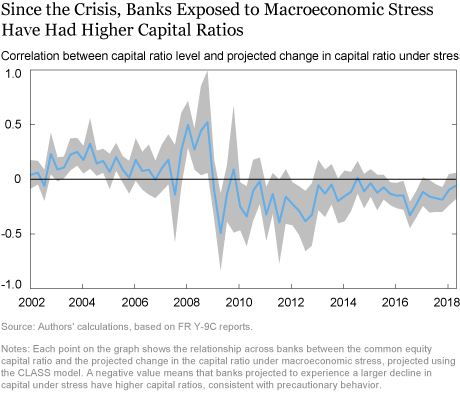

We also find some interesting changes in behavior across banks since the financial crisis. For each point in the 2002-18 period, we calculate the relationship between banks’ capital ratios and the projected change in their capital ratio under stress. In the chart below, we plot how this relationship has evolved over time. Since the crisis, the correlation has been negative—in other words, banks whose capital ratio is projected to decline the most under the stress scenario have higher observed regulatory capital ratios. This is consistent with “precautionary” behavior, in the sense that banks engaged in risky activities that are sensitive to economic stress are using more equity and less debt to finance themselves. We don’t observe such precautionary behavior before the crisis, when, in fact, the correlation was positive. One interpretation is that the flip in correlation reflects a greater emphasis on prudent capital planning since the crisis, perhaps as a result of the Federal Reserve’s annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review.

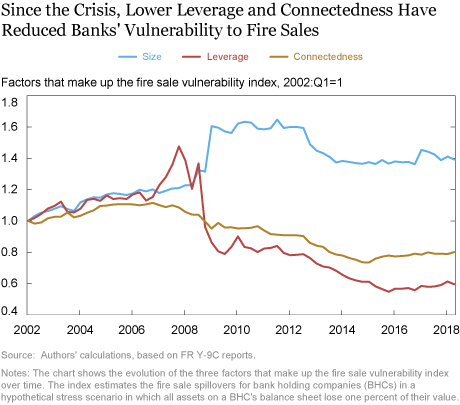

The fire sale vulnerability index almost doubled between 2002 and the financial crisis, clearly capturing the slow but steady buildup in systemic risk. By mid-2009, with the financial system stabilized, the index returned to average levels, where it stayed until 2013. After a two-year downtrend, the index then stabilized at a low level over the 2015-18 period. The index can be decomposed into three characteristics of the banking system: size, leverage, and “connectedness.” Size and leverage are aggregate properties; if banks merged or split, the total size and leverage of the system would remain unchanged. In contrast, connectedness depends on how different types of assets are distributed across banks. If larger and more levered banks tend to hold similar types of illiquid assets, then connectedness is high and fire sales would produce larger spillovers.

As shown in the chart below, the increase in fire sale vulnerability before the crisis was due in equal parts to increases in size, leverage, and connectedness. Around the time of the crisis, fluctuations in leverage were the main reason that banks’ vulnerability to fire sales peaked in the third quarter of 2008 and then declined in early 2009. Since the end of the crisis, the size of the banking sector has become the largest factor driving vulnerability to fire sales—in contrast to leverage and connectedness, which have steadily trended down, thereby driving the overall index down.

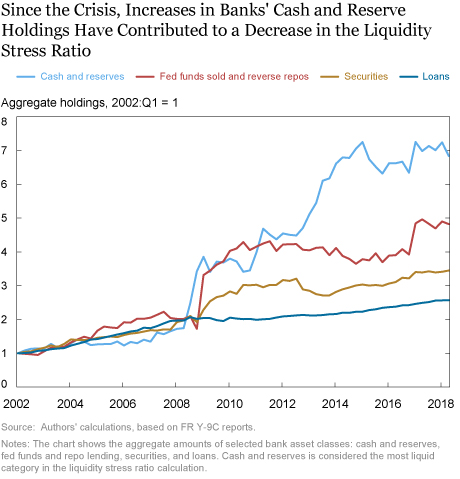

The aggregate liquidity stress ratio increased in the period leading up to the financial crisis, then decreased substantially after the crisis. Interestingly, the ratio peaked in the third quarter of 2007, a year earlier than the other measures. This might reflect the fact that banks were forced to adjust their balance sheet liquidity at the early stage of the crisis, when the private-label securitization market collapsed and the asset-backed commercial paper market dried up. As the next chart shows, the post-crisis improvement of liquidity stress has largely been driven by an increase in cash, which mirrors the increase in reserves owing to the Federal Reserve’s monetary stimulus.

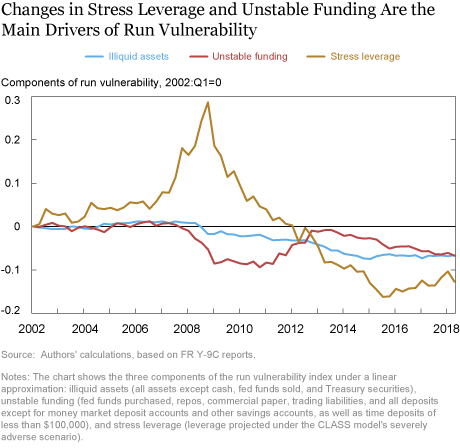

The run vulnerability index increased slowly in the pre-crisis period before sharply increasing, to about 60 percent, over the course of 2007. After remaining roughly flat through 2008, run vulnerability declined considerably below its pre-crisis level and is currently slightly above 10 percent. The run vulnerability index is the sum of three components. The first two are simple balance sheet measures: the fraction of illiquid assets and fraction of unstable funding. The third component is leverage under stress, as projected by the CLASS model.

The next chart shows that among these three components, stress leverage explains most of the long-run variation in run vulnerability. However, unstable funding had some interesting modulating effects. First, the decline in unstable funding that began in late 2007 offset the further increase in stress leverage and capped overall run vulnerability during the crisis at about 60 percent, preventing an increase to over 70 percent. In turn, the increase in unstable funding between 2011 and 2013 temporarily halted the post-crisis decline in run vulnerability.

All four of the measures suggest that the vulnerability of the financial system is low today when compared to pre-crisis standards, perhaps due to higher capital levels and liquidity holdings, but also because of muted growth and lower connectedness. However, all four measures appear to have stabilized in recent years, and some may already be on a slow upward trend.

What Do These Measures Miss?

Given their pre-crisis increases, these measures could have been informative if calculated at the time—underscoring their importance as a means of monitoring financial stability today. However, these measures certainly have limitations. First, they are largely based on regulatory variables and accounting data. Other research has shown the importance of also considering market data (Acharya, Engle, and Richardson, 2012; Sarin and Summers, 2016; Kovner and Van Tassel, 2018). Second, the measures all focus on banks, which were at the heart of the financial crisis but may not be at the epicenter of the next crisis. For example, recent research points to the growth in nonbank mortgage originations and servicing as a source of potential systemic risk. Finally, while the decline in systemic risk highlights the beneficial effects of post-crisis regulation, it doesn’t speak to the potential costs of those safeguards.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Dong Beom Choi is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Dong Beom Choi is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Fernando M. Duarte is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Fernando M. Duarte is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas M. Eisenbach is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas M. Eisenbach is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Vickery is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Vickery is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Dong Beom Choi, Fernando M. Duarte, Thomas M. Eisenbach, and James Vickery, “Ten Years after the Crisis, Is the Banking System Safer?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), November 14, 2018, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/11/ten-years-after-the-crisis-is-the-banking-system-safer.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics