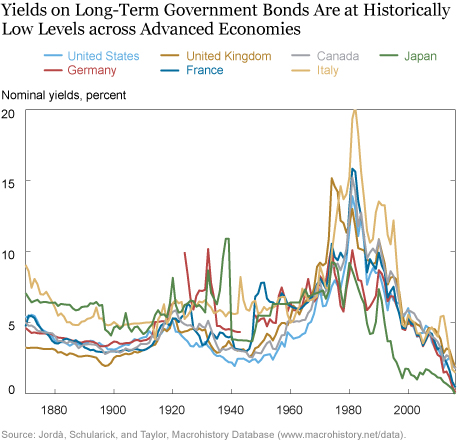

Long-term government bond yields are at their lowest levels of the past 150 years in advanced economies. In this blog post, we argue that this low-interest-rate environment reflects secular global forces that have lowered real interest rates by about two percentage points over the past forty years. The magnitude of this decline has been nearly the same in all advanced economies, since their real interest rates have converged over this period. The key factors behind this development are an increase in demand for safety and liquidity among investors and a slowdown in global economic growth.

These conclusions are based on the results of our recent New York Fed staff report, in which we jointly estimate trends in real rates for seven advanced economies using data on short- and long-term interest rates, inflation, and consumption starting in 1870. We do so through a flexible time-series model—a vector autoregression (VAR) with common trends. Employing this econometric tool, which we used in previous work, we can extract trends from a large number of variables without having to take a stance on the dynamic interdependencies among their cyclical components. Therefore, we can use economic theory to model and interpret these trends, while remaining agnostic on whether theory holds at other frequencies. For example, the absence of arbitrage opportunities in the long run implies that we can interpret the estimated common trend in real interest rates across countries as the trend in the world real interest rate. The same theoretical framework also allows for a decomposition of this trend into some of its potential drivers, such as global consumption growth.

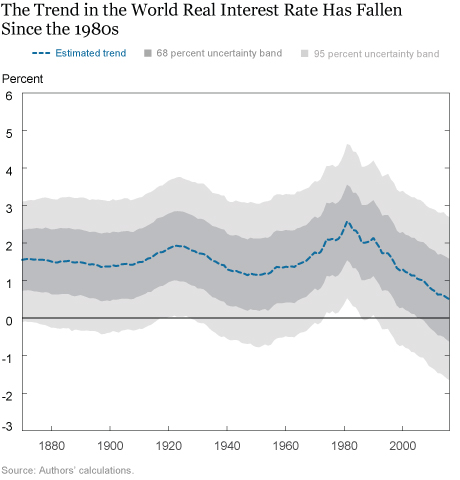

The first result of our empirical analysis is illustrated in the chart below, which shows the estimated trend in the world real interest rate (dashed line), together with 68 (dark grey) and 95 (light grey) percent uncertainty bands. According to these estimates, the trend in the world real interest rate was stable around values a bit below 2.0 percent through the 1940s. It rose gradually after World War II, peaking at close to 2.5 percent around 1980, but has been declining ever since, dipping to about 0.5 percent in 2016, the last year of available data. The exact level of the estimated trend is quite uncertain, but the drop over recent decades is precisely estimated. The size of this drop is also in line with the fall in the GDP-weighted estimates of r-star (the natural rate of interest) for the United States, Canada, the euro area, and the United Kingdom obtained by Holston, Laubach, and Williams. A decline of this magnitude—2 percentage points—is unprecedented in our sample. A drop of that size did not even occur during the Great Depression in the 1930s.

This finding might seem quite surprising, given the massive upheavals experienced by the world economy during the Great Depression and the World Wars. In contrast, Jordà and coauthors also document a fall in real safe rates since the mid-1980s, but find even larger declines around the World Wars and in the 1970s. Their conclusion is that “the puzzle may well be why the safe rate was so high in the mid-1980s, rather than why it has declined so much since then.”

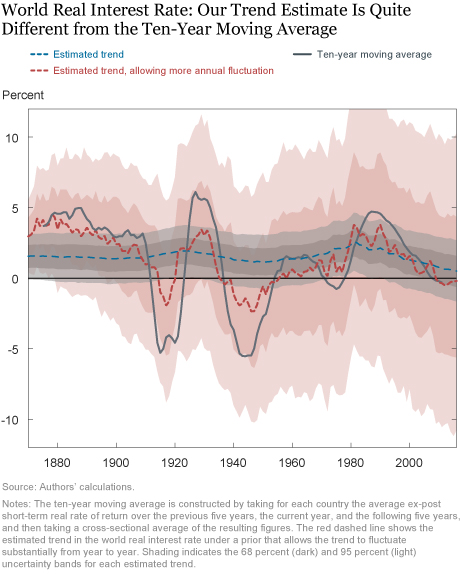

What explains the discrepancy between our findings and those of Jordà et al.? The chart above compares our measure of the trend in the world real interest rate (dashed blue line with gray bands) with the cross-country average of the ten-year moving average of the ex-post real interest rate in each country used by Jordà and co-authors (solid gray line). Clearly, the ten-year moving average is much more volatile than ours, plunging deep into negative territory around both World Wars. Why is that the case? The reason, we argue, is that ten-year moving averages conflate trends with cyclical variations. This is illustrated by the dashed red line in the chart, which shows that we obtain something much closer to the ten-year moving average if we allow the trend to fluctuate substantially from year to year. The implication of allowing the trend to fluctuate so much is that one cannot distinguish between cycle and trend, resulting in estimates of the trend that are very uncertain. This is apparent from the degree of uncertainty associated with the dashed red line (shaded red bands): The 68 percent uncertainty bands for the world interest rate trend are as large as 10 percentage points at the end of the sample!

Our prior beliefs on what represents a trend are quite conservative, with the expected change in the trend in our model having a standard deviation equal to one over a one-century horizon. However, our results are not very sensitive to modifications of the prior that reduce the horizon from one century to a half-century or a quarter of a century, or even a decade, as long as one does not use extreme values such as those implicit in the dashed red line (one year). Summing up, our conclusion that the decline in the global trend in interest rates over the past two decades is unprecedented is indeed robust to a wide range of prior views of what constitutes a trend, as long as one does not allow this trend to be unduly affected by cyclical developments.

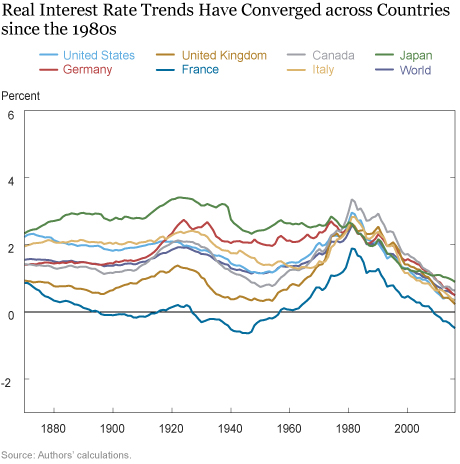

The next chart shows that the trend decline in the world real interest over the past forty years has been closely synchronized across advanced economies. The chart reports estimated trends in the real interest rates in the seven economies in our sample. Over this period, country-specific trends have essentially disappeared, so that the trend in the world real interest rate is now extremely close to the trends for all countries (with the possible exception of France). This convergence of real interest rate trends is consistent with the growing integration of global capital markets over this period. As a result, the secular decline in real interest rates is an eminently global phenomenon, with the trends in real rates falling by very similar amounts in all advanced economies. The finding that a “global trend” in real interest rates has increasingly overshadowed country-specific trends presents interesting similarities with the results of recent work that emphasizes the emergence of a “global cycle”—or global factor—as a growing source of co-movement in the returns of risky assets around the world (for example, see Gerko and Rey).

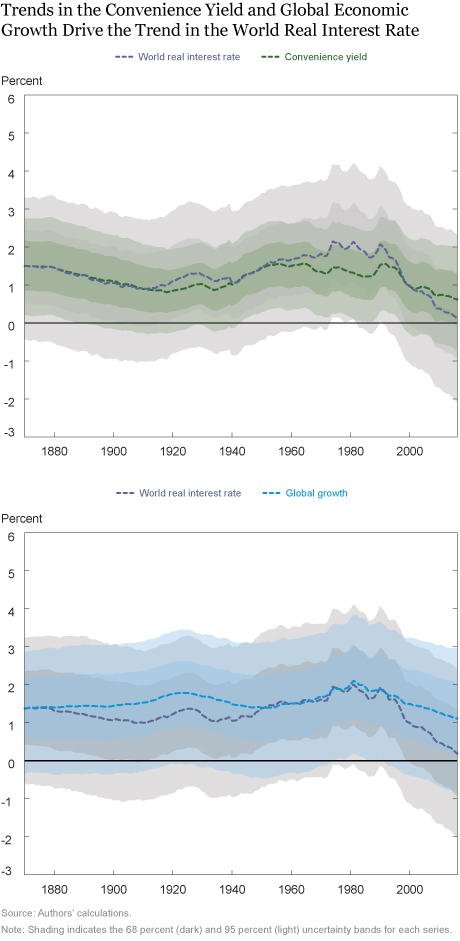

Finally, the chart below presents the contribution to the evolution of our estimate of the world real interest rate of some of its fundamental components. In particular, we focus here on two factors that are potential drivers of the low-interest-rate environment: convenience yields and global economic growth. The convenience yield is the amount of interest that investors are willing to forgo in exchange for the liquidity and safety benefits of high-quality securities. Convenience yields are likely to be a relevant factor in our data set because the interest rates that this series contains are on either government securities or close substitutes, which are relatively safe and liquid compared to other privately issued assets. As a consequence, our world real interest rate trend series captures the trend in real interest rates on safe and liquid securities. To measure this convenience yield, we include in the estimation Moody’s Baa corporate bond yield for the United States, as in Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen. Under certain assumptions, which we discuss in our staff report, this information is sufficient to capture the long-run effect of convenience on the world interest rate.

The upper panel in the chart above reports the contribution of the estimated convenience yield factor to the trend movements in the world real interest rate. This decomposition shows that the trend decline in the world real interest rate over the past few decades has been driven to a significant extent by an increase in the trend component of the world convenience yield (the dashed green line actually plots its negative value, while the green shaded areas are the associated 68 and 95 percent uncertainty bands). This increase in the world convenience yield trend points to a growing imbalance between global demand for safety and liquidity and the supply of securities with such properties. This contribution is especially pronounced since the mid-1990s, supporting the view that the Asian financial crisis of 1997 and the Russian default in 1998, with the ensuing collapse of Long-Term Capital Management, were key turning points in the emergence of global imbalances, as argued, for instance, by Bernanke, Caballero, Caballero and Farhi, and Gourinchas and Rey, among others.

The lower panel of the chart above shows the contribution associated with the trend in global economic growth. The latter is estimated as a common component of trends in the growth rate of per capita consumption across the seven economies in our sample, as suggested by the consumption asset pricing model and further detailed in our paper. A global decline in the growth rate of per-capita consumption, possibly linked to demographic shifts, is a further notable factor pushing global real interest rates lower. Its contribution is comparable in magnitude to that of the convenience yield since 1980, but is only about half as important over the past twenty years (and less precisely estimated).

Taken together, our results suggest that low interest rates in advanced economies are a secular phenomenon driven by global forces that emerged well before the Great Recession and that are unlikely to be connected to country-specific factors, such as national policies or other domestic developments. Therefore, whatever forces might lift real interest rates in the future must be global, such as a sustained pickup in world economic growth, or a better alignment of global supply and demand with respect to safe and liquid assets.

This post has been reprinted, with minor changes, from the VoxEU.org blog. The original post appeared on November 12, 2018.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Marco Del Negro is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Del Negro is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Domenico Giannone is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Domenico Giannone is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marc Giannoni is a senior vice president and director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Marc Giannoni is a senior vice president and director of research at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Andrea Tambalotti is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Andrea Tambalotti is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Brandyn Bok is a former research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Eric Qian is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Eric Qian is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Do you think that until the generation of baby boomers is gone and pressures on healthcare, pensions and social security starts to significantly decline, we could really return to a high(er) interest rates environment? I am making quite a shortcut on purpose but seeking your views on the correlation between these facts and the Fed policy on rates.

Good article. I would suggest that going forward we shall see rising rates in both corporate and sovereign credit. The credit markets have a lot of debt issued, record debt, and more to come. As well as record rising low quality investment grade debt, BBB. Credit yields shall reflect the rising Risks and liquidity.