The United States lost 5.7 million manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2010, reducing the nation’s manufacturing employment base by nearly a third. These job losses and their causes have been well documented in the popular press and in academic circles. Less well recognized is the modest yet significant rebound in manufacturing jobs that has been underway for several years. Indeed, employment in the manufacturing industry began to stabilize in 2010, and the nation has added nearly 1 million jobs since then. Although modest in magnitude, this uptick in manufacturing jobs represents the longest sustained increase since the 1960s and bucks a decades-long trend of secular decline in employment in the goods producing sector of the economy. This is the first of two posts on the rebound in manufacturing jobs. In this post, we outline the manufacturing jobs recovery and assess which sectors within the manufacturing industry are driving this increase. The second post will focus on the geography of the manufacturing employment rebound. It will examine where manufacturing jobs are growing and where they are continuing to decline, with a focus on how areas in the New York-Northern New Jersey region have fared.

In 1980, there were close to 20 million manufacturing jobs in the United States, a figure that declined to around 12 million following the Great Recession. Much of this decline was concentrated in recessions—though the business cycle in and of itself is not the main driver of the waning of manufacturing jobs in recent decades. Many of these jobs simply disappeared and did not come back during the subsequent recoveries. Technological advances, particularly automation, as well as globalization, particularly rising import competition from China, are the primary contributors to this long-term decline in manufacturing employment. A surprisingly large portion of this decline occurred between 2000 and 2010, when the nation lost 5.7 million manufacturing jobs. However, employment stabilized beginning in 2010, and nearly a million manufacturing jobs have been gained since then. While this may not seem like much on the heels of such a momentous decline, this sustained increase in manufacturing employment represents the longest such stretch since the 1960s, and the nation has not added this many manufacturing jobs since the 1970s.

Changes within the Manufacturing Industry

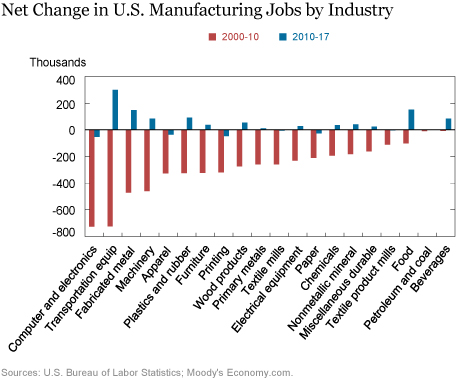

Although the manufacturing industry as a whole saw a large employment decline followed by a modest rebound, some sectors within the manufacturing industry have seen a substantial uptick in jobs over the last several years, while other sectors continue to shed jobs. The chart below shows the net change in manufacturing jobs by industry for the 2000-10 period compared to the 2010-17 period.

Between 2000 and 2010, every sector within the manufacturing industry lost jobs. The most significant declines occurred in the computers and electronics industry and the transportation equipment industry. These two industries provide a case in point about the two driving forces that have pushed down manufacturing employment so significantly in recent decades. The transportation equipment industry lost nearly 730,000 jobs during this ten year period, due in large part to productivity gains tied to automation. The computers and electronics industry shed more than 720,000 jobs between 2000 and 2010. While also seeing productivity gains reducing the need for workers, many industries have faced intense competition from overseas, and outsourcing and offshoring has become widespread. Apparel is an example of an industry that suffered severe job losses in the United States as production shifted overseas. Other industries, such as fabricated metals and machinery, saw steep job losses due to a combination of productivity gains and import competition. At the other end of the spectrum, job losses were minimal in the food, beverages, and petroleum and coal industries.

The bounce back in manufacturing jobs has been led by the transportation equipment industry, which added around 300,000 jobs, roughly a third of the net increase over this period. As the costs of overseas labor and shipping products from other parts of the world have climbed, manufacturers started to bring jobs back to the United States. Such reshoring of manufacturing jobs has been particularly pronounced in the automotive industry. The fabricated metals and machinery industries—which were hit hard between 2000 and 2010—also saw significant gains, together adding about 230,000 jobs. Fueled by strong domestic demand throughout the expansion following the Great Recession, the food and beverages industries—which had largely been insulated from job losses during the early 2000s—saw a combined increase of nearly 240,000 jobs.

Looking Ahead

Despite the recent increase in jobs, the nation’s manufacturing employment base is a fraction of what it was in the early 1980s, even as output in the sector has continued to increase. Whether manufacturing jobs continue to grow going forward is an open question. No doubt, recent tariffs and associated trade policy uncertainty pose significant challenges for continued job growth in the manufacturing industry, particularly in sectors that rely on steel and aluminum as inputs to the production process.

In our next post, we will look at where within the United States manufacturing jobs have been growing. It turns out the places that lost the most manufacturing jobs are not necessarily the ones where those jobs are coming back.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “The (Modest) Rebound in Manufacturing Jobs,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), February 4, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/02/the-modest-rebound-in-manufacturing-jobs.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your question. As we mention in the post, there have been two main drivers of the downward trend in U.S. manufacturing jobs. First, technological developments have enabled manufacturers to produce more with fewer workers; for example, by using robots or other computer-assisted technologies. Second, greater globalization has allowed the U.S. to import more labor-intensive manufactured goods from countries with lower labor costs. As to the reasons behind the partial rebound in manufacturing jobs since 2010, that remains an open question. Some of the factors you mention may very well be at play, such as rising labor and other costs abroad.

I would be interested in theories regarding the cause of the decline; was it due to labor costs? Lack of manufacturing expertise – particularly regarding Hi-tech? Why is manufacturing rebounding? Are costs equalizing with the rest of the world? Are tax policies having an impact? Thanks Gary Dittmer