From 2008 to 2014 the Federal Reserve vastly increased the size of its balance sheet, mainly through its large-scale asset purchase programs (LSAPs). The resulting abundance of reserves affected the financial system in a number of ways, including by changing the intraday timing of interbank payments. In this post we show that (1) there appears to be a nonlinear relationship between the amount of reserves in the system and the timing of interbank payments, and (2) with the increase in reserves, smaller banks shifted their timing of payments more significantly than larger banks did. This result suggests that tracking the timing of payments sent by banks could provide an informative signal about the impact of the shrinking Federal Reserve balance sheet on the payments system.

How Do Reserves Affect the Timing of Interbank Payments?

As part of the normal course of business, banks are required to make payments to one another to settle a variety of obligations. Banks typically draw on the reserves they hold at the Federal Reserve to make these payments, using the Fedwire® Funds Service (Fedwire), a large-value payments system operated by the New York Fed. Banks often send and receive a larger amount of reserves than they have in their accounts, which creates the potential for banks to overdraft on their accounts during the day. To facilitate the flow of payments, the Federal Reserve allows banks to overdraft on their accounts within the day by providing them with intraday credit at a low cost.

Before 2008, the Federal Reserve maintained a low level of total reserves. Consequently, banks had to be vigilant about the within-day timing of their payments so as to minimize the amount of intraday credit they needed. Banks often sought to minimize this need for intraday credit by delaying the payments they were obligated to make until they received payments from other banks. This approach resulted in Fedwire payments becoming concentrated at the end of the day.

With the implementation of the LSAPs, reserves rose to a high level. One consequence of this change was that banks were now able to make payments throughout the day with less concern about having to access intraday credit. As a result, banks began to send payments to one another earlier in the day.

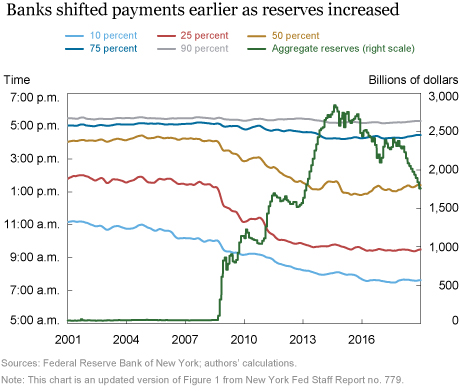

This phenomenon is illustrated in the chart below. For each day in the sample period, we calculate when 10, 25, 50, 75, and 90 percent of the day’s total value has been transferred over Fedwire. For example, in June 2001, 10 percent of total Fedwire activity had been sent by about 11 a.m., 25 percent by about 2 p.m., 50 percent by 4 p.m., 75 percent by 5 p.m., and 90 percent by about 5:30 p.m. Notably, before 2008, half of the day’s total value had been transferred by around 4 p.m., whereas currently, that share is transferred by around 1:30 p.m. This shift demonstrates that banks are now sending payments earlier in the day.

The green line in the chart above reflects the total amount of reserves held by banks. The juxtaposition of this line with the payments lines illustrates what appears to be a nonlinear relationship between the timing of payments within the day and the total amount of reserves in the system. In particular, the increase in reserves from late 2008 to 2012 had a larger impact on the timing of payments than subsequent increases in reserves did. Another likely factor in the change in within-day payments timing was the March 2011 revision in Federal Reserve policy around providing intraday credit.

Are All Banks Affected Similarly?

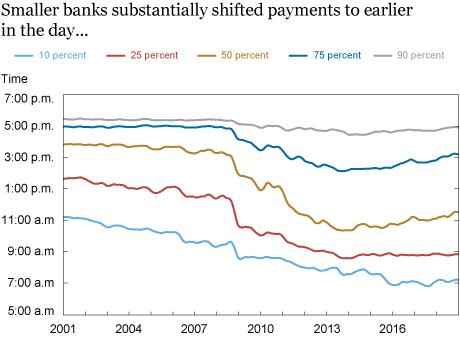

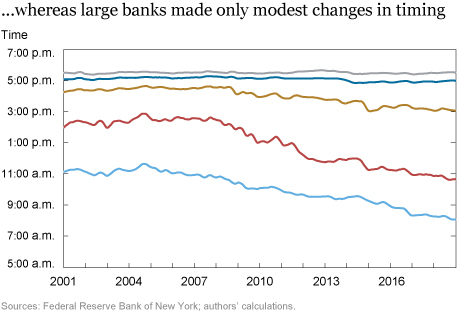

Did the increase in reserves affect the timing of payments for large banks differently from that of smaller banks? To explore this question, we look at the total value of annual payments sent in 2006 and form a group of the largest 10 accounts on Fedwire, which together represented about 60 percent of all payments sent, and a second group for all other accounts (“non-top 10 accounts”). Strikingly, the shift in payments timing was larger for the non-top 10 accounts. With the increase in aggregate reserves, this group of smaller accounts began sending half of its daily payments before 11 a.m. (see the 50 percent line in the first chart below). In contrast, the top 10 accounts sent half of their payments by roughly 3 p.m. (see the second chart below). A similar pattern is seen with the timing of the 25 and 75 percent shares of total activity. Hence, in the current period of abundant reserves there is a notable difference in behavior between the largest banks and smaller banks, a difference that was much less pronounced in the pre-crisis period of scarce reserves.

Takeaway

The within-day timing of payments is a gauge of banks’ level of reserves and their decisions about accessing intraday credit to fulfill their obligations. As the Federal Reserve drains reserves as part of its balance sheet normalization program, changes in the timing of payments to later in the day could serve as a real-time signal that reserves are becoming scarce enough for banks to change how they manage their reserves and interbank payments flows.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Adam Copeland is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Linsey Molloy is a senior associate in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Linsey Molloy is a senior associate in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Anya Tarascina is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Adam Copeland, Linsey Molloy, and Anya Tarascina, “What Can We Learn from the Timing of Interbank Payments?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), February 25, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/02/what-can-we-learn-from-the-timing-of-interbank-payments.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

This is an excellent and timely posting. The implication for the financial-stability benefits of more-than-minimally sufficient reserves is clear. It takes time for reserves to flow through the payments network from those who have extra on a given day to those who need more. With a tight supply, especially on stressful days, there is plenty of evidence that some banks will hold back their sends until they get a good measure of what they are due from others. This can cause congestion.