By November 2008, the Global Financial Crisis, which originated in the residential housing market and the shadow banking system, had begun to turn into a major recession, spurring the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to initiate what we now refer to as quantitative easing (QE). In this blog post, we draw upon the empirical findings of post-crisis academic research–including our own work–to shed light on the question: Did QE work?

Unconventional Monetary Policy and Quantitative Easing

First things first: What does the term QE describe? QE is part of what is now referred to as unconventional monetary policy. Over the two decades prior to the Global Financial Crisis, central banks mainly conducted monetary policy through two instruments. First, a central bank would set the short-term money rate—in the United States, the fed funds target rate. Second, the central bank would try to “manage expectations” by giving the public a sense of where the future policy rate would be through its official communications with the public. This way of conducting monetary policy is based on the premise that a lower (expected) interest rate will lead to an expansion of economic activity, enabling the central bank to minimize economic volatility over the course of the business cycle and to fulfill its (explicit or implicit) mandate to achieve price stability and maximum employment.

When the nominal interest rate is close to zero, this way of supporting the economy becomes less effective; should a central bank consider negative nominal rates to be an option, the effectiveness of the tool is still limited, since nominal rates can only be pushed so far below zero. Alternatively, the central bank can attempt to support the economy by buying large amounts of financial assets to make risky assets more liquid and/or lower longer-term interest rates. A form of unconventional monetary policy, these large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) are often simply referred to as QE.

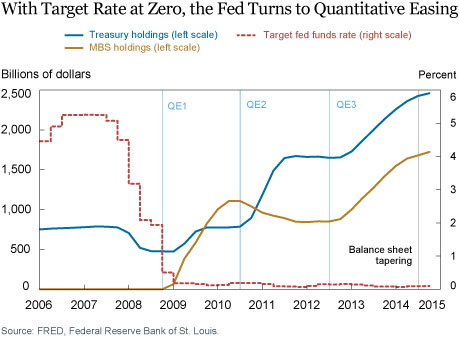

After the financial-market disruptions experienced during the summer of 2007, the FOMC started to lower the fed funds target rate. However, the fed funds target rate lost its power to provide further stimulus to the economy when it reached the zero lower bound in December 2008 (see the chart below). Over the next several years, the Fed conducted three rounds of LSAPs:

- On November 25, 2008, the FOMC announced what came to be known as QE1: The Fed would buy up to $100 billion of direct debt obligations issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and an additional $500 billion of agency MBS. The program was extended and expanded in March 2009, and, by the end of QE1 in March 2010, the Fed had bought $1.25 trillion in MBS, $175 billion in federal agency debt, and $300 billion in U.S. Treasury securities.

- In August 2010, the FOMC signaled the start of a second round of quantitative easing (QE2), which was then officially implemented in November 2010. QE2 consisted of a total purchase of $600 billion in long-term Treasury securities.

- Finally, the FOMC announced a third round of quantitative easing (QE3) in September 2012, calling for monthly purchases of $40 billion in agency MBS and, starting in January 2013, $45 billion in U.S. Treasury securities as well.

Did QE Work? What the Data Suggest

The three rounds of QE were controversial at the time, and they remain so today. Some observers have argued that QE creates new risks for financial stability or inflation but is not helpful in fulfilling the Fed’s mandate to achieve price stability and maximum employment. Using empirical data to test such claims is challenging, since it is difficult to draw causal inferences from macroeconomic events. This conundrum is described well in Ben Bernanke’s memoir The Courage to Act, where he writes, “We can’t know exactly how much of the U.S. recovery can be attributed to monetary policy, since we can only conjecture what might have happened if the Fed had not taken the steps it did.”

With this caveat in mind, we nonetheless discuss a selection of empirical findings that now, ten years later, give us some sense of how QE may have affected the real economy.

1. Yields: QE had a large impact on the yields of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities and the effect varied across the different rounds of QE. These findings are presented by Krishnamurthy and Vissing Jorgensen (2011, 2013), who, among other things, illustrate that QE1 and QE3 decreased MBS and Treasury yields. However, the authors also show that MBS yields were more strongly affected (across both rounds) and QE3’s effect on MBS yields was much smaller than that of QE1. Moreover, the authors show that QE2, which consisted only of Treasury purchases, had very weak effects on yields.

2. Mortgage refinancing: Building on this finding, Di Maggio, Kermani, and Palmer (2018) show that when the Fed bought MBS during QE1, it led to a boom in the refinancing of existing mortgages, in particular those types of mortgages that are eligible for purchase by the Fed. Refinancing an existing mortgage at a lower interest rate increases the respective household’s net worth as its debt burden is decreased. Increased net worth, in turn, allows households to increase their consumption. QE can thus stimulate aggregate demand by making refinancing of mortgages attractive. However, for this channel to be active, household leverage becomes a crucial factor. In particular, Beraja et al. (2018) provide evidence that in areas in which households have higher leverage, and are hence more likely to owe more than their homes are worth, this channel is impaired.

3. Bank lending: Another important finding is presented by Darmouni and Rodnyansky (2017), who study the effect of QE on bank lending more generally. The authors show that banks that owned more MBS prior to QE saw faster growth in loans to firms and households than banks that had little or no MBS holdings. This indicates that, by purchasing MBS, the Fed was able to stimulate additional credit provision by banks. In particular, the authors provide evidence that the credit stimulus stems from QE making banks’ assets more liquid.

Combined Effects on Real Economic Activity

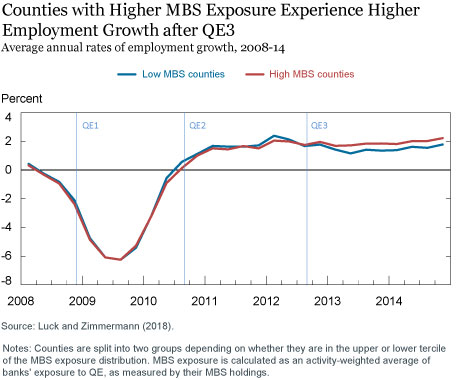

The question that then arises is whether the additional credit provision resulted in additional real economic activity, thereby helping to fulfill the Fed’s mandate. In our paper, we build on the existing research discussed above and ask whether the additional lending from banks has real effects, such as an increase in employment, consumption, or investment. Our empirical strategy exploits the fact that some banks are more affected by the Fed’s asset purchases than others, as suggested by Darmouni and Rodnyansky (2017). We also draw on the fact that bank activity varies geographically. Given that employment and consumption data are available at the regional level, we can hence construct a link between bank lending and real activity. We track which regions received most of the additional credit after a given round of QE and study how credit growth correlated with change in local consumption, investment, and employment.

Our paper reveals that the impact of QE1—an increase in commercial banks’ mortgage refinancing activity—had effects on local consumption and employment in the nontradable goods sector, but no overall employment effects. In contrast, QE3-driven increases in commercial and industrial lending and home mortgage originations translated into sizable growth in overall employment. The main results are best illustrated in the chart below, which plots the average growth of employment in two sets of counties: those whose banks had high MBS exposure and those whose banks had low MBS exposure. While there is virtually no differential effect after QE1 and QE2, there is a substantial difference after QE3.

To Sum Up

Altogether, the empirical studies of recent years suggest that large-scale asset purchases can affect real economic outcomes via a bank lending channel. Like an interest rate cut in a conventional monetary policy setting, QE can lead to additional bank lending, which in turn translates into additional economic activity.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Stephan Luck is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Zimmermann is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Cologne.

How to cite this blog post:

Stephan Luck and Thomas Zimmermann, “Ten Years Later—Did QE Work?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), May 8, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/05/ten-years-laterdid-qe-work.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Dear readers, Thank you for your interest in the post. I will address a number of the points raised in your comments here. First, some definitions: QE, or “quantitative easing,” is a type of unconventional monetary policy. In the context of this blog post, it describes the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase programs (LSAPs). Mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are collateralized claims on payments from one or more mortgages. Agency MBS are MBS originated by government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). Regarding our findings: We see some evidence that the financing conditions for firms and households, and hence real economic activity, would have been worse absent the Federal Reserve’s actions. Further, we find that, after QE3, counties in the upper tercile of the MBS exposure distribution have higher employment growth (by around 50 basis points per quarter) than counties in the lower tercile. The effect is not only statistically significant but also economically significant. Regarding the challenge of establishing causality: As we mention in the blog post, it is inherently quite difficult to tease out what exactly the effects of a given macroeconomic policy are. However, we believe our evidence shows that, while QE could have had many effects on many different outcomes, it likely had a positive effect on employment. We went to great lengths in our study to avoid falling into analytical traps. For instance, our paper carefully documents and controls for observable differences between high-MBS counties and low-MBS counties. Altogether, even though we don’t know what growth would have been absent QE, we believe our findings are indicative of a positive effect of QE on real economic activity. — Stephan Luck

10 may 2019 friday manila ph “did qe work?” https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/05/ten-years-laterdid-qe-work.html first of all i am not an economists. but i do believe, i hardly know and fully understands how economy works in our life. in every coin there’s always two sides. on one side, if the fed did not use qe to 2008year meltdown, all countries in this world will experience 1930s depression. that’s why i use second great depression in all my writings. on the other side because they used “qe” to the 2008year meltdown or exactly right after they used it, released this qe, all countries today are now drowning on death, definitely swimming on “debt”. now the question is, what is the difference between the two sides of the coin? simple, in every problem there is always an actual, correct, logical solutions, an absolute answer to the problem. meaning in every illness there is always a right, correct, effective, 100percent remedy or cure to the illness. but once you missed, made a mistake, my God . . . . . . . you are curing one side and absolutely killing the other side. no one knows that this is the real picture of todays’ economy. God bless . . . . . . . raul fb: thegreatdepression.part2@yahoo.com

Any discussion about the impact of QE (and American monetary policy in the wake of the financial crisis in general) needs to mention interest on excess reserves. QE put money into the economy. But IOER took money out again, and especially for banks competes directly against lending. The net effect is not obvious. See eg https://www.alt-m.org/2017/10/03/strange-official-economics-of-interest-on-excess-reserves/

If you want more bank lending there are much easier ways to make that happen than with a massive intervention in the credit markets. Just reduce reserve requirements and with the stroke of a pen you get more bank lending. The increase in growth is also minuscule. Did you do a test for statistical significance? Finally you fell into the oldest trap in statistics which is that correlation does not mean causation. The fact that there was lower MBS activity in counties that had lower growth does not prove that the lower MBS activity caused the lower growth. Those counties could well have had fewer homes for sale in total which might have meant less economic activity overall, which could have well been the cause of the lower growth. The real assessment of the Obama years is that GDP growth never got above 2% despite massive fiscal stimulus ($860B) and three rounds of QE. Which just goes to prove that the Federal government cannot financial engineer the country to prosperity. The Trump program of getting the Federal government out of the way of the private sector works much better.

QE and what took place after 2008 did not actually work. QE created growth on Debt, mainly non self liquidating debt. We now are faced, around the Globe, record Debt and majority is of low quality and junk. This has created greater problem as the Global economies slow down. Deflation is taking hold and Deflation will take its toll on Debt. The Central Banks should have stepped back and take the required corrective action that has caused the economic issues and financial fundamentals rather than flooding the system with cheap unproductive money and non self liquidating debt

Except for initially unfreezing markets QE failed. 71 cents out of every dollar of QE ended up as overnight funds or very short term investments on the balance sheets of banks, credit unions and thrift, and is still there do to the Fed increasing liquidity and capital standards. Depositories $500 Million or less in assets have still not recover to loan levels prior to 2008. Underwriting standards still have not recovered from pre-Great Recession standards. It is still hard for small businesses to get credit especially for unsecured loans. Small businesses of less than 25 people are the back bone of US commerce. The Fed’s own studies show this. Based on the above I disagree with the authors

What does the term QE describe?………. A description of Mortgaged Based Securities would also have benefited the study. Thanks Joe K