Editors Note: An updated version of this post is available here. (April 21, 2025)

In our last post, we showed that the cost of college has increased sharply in recent years due to the rising opportunity cost of attending school and the steady rise in tuition. This steep increase in the cost of college has once again raised questions about whether college is “worth it.” In this post, we weigh the economic benefits of a bachelor’s degree against the costs to estimate the return to college, providing an update to our 2014 study. We find that the average rate of return for a bachelor’s degree has edged down slightly in recent years due to rising costs, but remains high at around 14 percent, easily surpassing the threshold for a good investment. Thus, while the rising cost of college appears to have eroded the value of a bachelor’s degree somewhat, college remains a good investment for most people.

The Economic Benefit of a College Degree

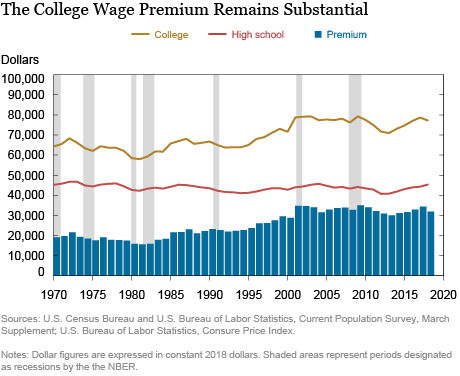

College graduates tend to earn a substantial wage premium in the labor market. Below we plot the average annual wages of college graduates compared to those with only a high school diploma, adjusted for inflation and demographic differences between the two groups. (See our 2014 study for details on the methodology used for these calculations, as well as important caveats, which we revisit below.) In recent years, the average college graduate with just a bachelor’s degree earned about $78,000, compared to $45,000 for the average worker with only a high school diploma. This means a typical college graduate earns a premium of well over $30,000, or nearly 75 percent. This “college wage premium” has fluctuated over time, as shown in the bars at the bottom of the chart. The college wage premium generally increased during the 1980s and 1990s, rising from less than $20,000 to around $30,000, before settling into a relatively narrow range of $30,000 to $35,000 after 2000.

Notably, while the strong labor market has boosted the wages of those with a high school diploma in recent years, the wages of college graduates have gone up by as much or more, keeping the college wage premium near an all-time high. Indeed, the labor market for college graduates has not been this strong since well before the Great Recession. Because the economic benefits of a college degree last over an entire career, we estimate this wage premium over a more than forty-year working life, using an approach explained in detail in our 2014 study. This yields an estimate of the total benefit of a college degree that can be weighed against the costs.

Weighing the Economic Costs and Benefits

As with any investment, the costs and benefits of college accrue over different time intervals, making it a bit tricky for students and their parents to judge the economic value of a degree. Indeed, for the typical college student, the costs of college result in a negative cash flow while in school (assumed to be four years for a bachelor’s degree), followed by a positive cash flow (the college wage premium) received over one’s entire career. In order to weigh the upfront costs against the lifetime benefits, we calculate the internal rate of return—a measure investors commonly use to gauge the profitability of different kinds of investments. Given the complexities involved, these figures should be viewed as back-of-the-envelope estimates, and are meant to provide only a rough guide to the value of a college degree for the average undergraduate.

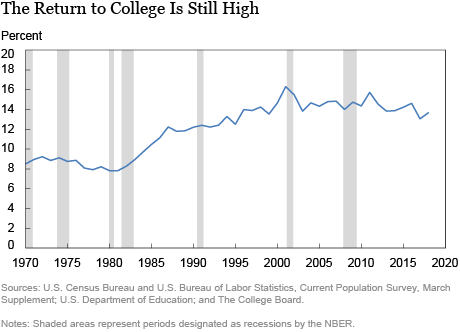

The chart below plots the rate of return for a bachelor’s degree since 1970. We estimate that the return to college hovered between 8 and 9 percent until the early 1980s, then climbed to almost 16 percent following the technology-fueled economic expansion of the 1990s, where it remained, more or less, through the Great Recession. Over the past several years, this return appears to have declined slightly, drifting down by roughly 2 percentage points to just under 14 percent.

Why has the return to college fallen in recent years? Rising costs are mostly to blame. While the college wage premium has held steady—or even increased slightly—in recent years, costs have been increasing due to rising opportunity costs and a steady rise in tuition. However, rising costs and falling returns do not necessarily mean that going to college isn’t worth it anymore. At nearly 14 percent, the return to college easily exceeds various investment benchmarks, such as the long-term return on stocks (7 percent) or bonds (3 percent). Thus, while the rising cost of college has eroded the return to a bachelor’s degree to some extent, our analysis suggests that college remains a good investment, at least for most people.

Of course, there are some important caveats to keep in mind with our back-of-the-envelope calculations. We can’t rule out the possibility that some of what we estimate as the return to college is not a consequence of the knowledge and skills acquired while in school, but rather is a reflection of the innate skills and abilities possessed by those who complete college. However, our estimates are in line with an extensive body of research that is better able to correct for such possibilities. In fact, one study examining the return to college for academically marginal students indicates that the payoff to college for such students is as large as our estimates suggest, if not larger. In addition, as we have discussed before, taking more than four years to complete a bachelor’s degree significantly reduces the return to college. Moreover, these figures are based on the experience of the average college graduate. We have shown previously that college does not appear to have paid off for roughly the bottom 25 percent of those who made the investment. And, perhaps most importantly, our estimates apply to those that complete a degree—college dropouts incur at least some of the costs, but enjoy far fewer benefits.

College Is Still a Good Investment

In recent years, the rising cost of college has eroded the value of a bachelor’s degree somewhat. However, the college wage premium has remained near its all-time high and the return to college now stands at around 14 percent—easily surpassing the threshold for a good investment. While the rising cost of college may be troubling, it has not yet changed the basic calculus as to whether earning a college degree is worth it. The benefits still outweigh the costs, at least for most people.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “Despite Rising Costs, College Is Still a Good Investment,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), June 5, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/06/despite-rising-costs-college-is-still-a-good-investment.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Some might find this article that Lisa Burke-Smalley and I published last year additionally illuminating. We specifically model time-to-graduation and calculate the selection-adjusted NPV and IRR for different areas of study. We also provide some guidance on breakeven tuition thresholds and the effects of debt financing. Article available here: https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2017.1332167

Because better paying jobs generally go to people with more education, it is no surprise that studies typically find that the expenses of college are worth it for individual students. If 20% of the working population has a degree, they will typically be in the top 20% of jobs. If 80%, they will typically be in the top 80% of jobs. But there is an economic cost to students and society from “credential creep” — requiring a college degree for a job that can be done with a solid high-school education and some on-the-job training. I have yet to see a study addressing this question. Moreover, if college is such a good investment, there should be a way to place at least some of the financial risk on the colleges, and not have them be entirely borne by students.

The original 2014 study used data from 2012. What year of data is this new update calculated on?

Thanks to all readers who posted comments. We respond to a number of queries in this note. As for what we assume about the earnings path of a typical worker, we estimate total wages over one’s entire working career using various statistical techniques, which we outline in some detail on our earlier study (https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/current_issues/ci20-3.html). Essentially, we model lifetime earnings profiles where earnings vary by age from 22 to 64 for college graduates and 18 to 64 for high school graduates, and use these figures to calculate the college wage premium values that factor into our rate of return analysis. This is different than the average wages we cite in the first chart in our post, which is meant to provide only a rough estimate of how the average college wage premium has evolved over time, and is not used in our rate of return estimates. We do publish estimates of average early- and mid-career wages earned by college graduates overall and by major on our website the Labor Market for Recent College Graduates (https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market/college-labor-market_compare-majors.html).

The prudent approach would be to make higher education more affordable *and* improve quality and outcomes. With traditional institutions that is a tall order, due to existing stakeholder dynamics and constraints… We are tackling this from a position of an outsider/new entrant: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190611005272/en/NewU-Develops-Solution-Student-Debt-Crisis

I find it ironic that I have to pay to read the research these gentlemen referenced in their article. Typical. I have to spend money to access research meant to prove that it is worth spending money to get an education. Please provide the research for free so that discerning readers can make an informed choice. https://lnkd.in/g295ZNN

This generally confirms research I published in 2007 in the Journal of Student Financial Aid. However, it doesn’t take the next step, which is to calculate the financial value of higher education to the federal government. The higher income yields higher federal income taxes. How does that compare to the cost to the federal government?

What is the assumed years of employment or age of this prototypical individual? Fresh out of college, i.e. 22-years old or 10-years in the working force – if so 10-years for the college individual and 14-years for the high school…etc.? I ask because although I can see the $20-35k/yr “college wage premium” being a fair representation of delta between the two scenarios; I don’t buy for a second that a fresh graduate in any field (except maybe medical doctor?) would be offered a $78,000/yr employment opportunity. If that is truly the assumption, then I must rethink the stock I put in the Fed’s numbers henceforth.

I beg to differ that college is a good investment and much of my argument is in my blog called “College Meltdown.” Clearly, going to college for working families is a risky investment, not just with subprime colleges, but with many liberal arts schools and large research universities. https://collegemeltdown.blogspot.com/

Does this suggest that by and large even if a student loan costs, say, 12% I’m still coming out ahead since I’m generating a 14% IRR?