College is much more expensive than it used to be. Tuition for a bachelor’s degree has more than tripled from an (inflation-adjusted) average of about $5,000 per year in the 1970s to around $18,000 today. For many parents and prospective students, this high and rising tuition has raised concerns about whether getting a college degree is still worth it—a question we addressed in a 2014 study. In this post, we update that study, estimating the cost of college in terms of both out-of-pocket expenses, like tuition, and opportunity costs, the wages one gives up to attend school. We find that the cost of college has increased sharply over the past several years, though tuition increases are not the primary driver. Rather, opportunity costs have increased substantially as the wages of those without a college degree have climbed due to a strong labor market. In a follow-up post, we will consider whether college is still “worth it” by weighing the benefits relative to the costs to estimate the return to a college degree.

Tuition Is Only Part of the Cost of a College Degree

The economic cost of college has two components. The first is out‑of‑pocket costs, which are expenses associated with attending college that wouldn’t otherwise be incurred. Tuition and fees are out-of-pocket costs, but room and board aren’t since they need to be paid regardless of whether one is in school. The second component is opportunity cost, which represents the value of what someone must give up in order to attend college. For most people, the opportunity cost of a college education is equivalent to the wages that could have been earned by working instead of going to school. It turns out that the opportunity cost of college is much more substantial than out-of-pocket costs, though both have been climbing in recent years.

Out-of-Pocket Costs

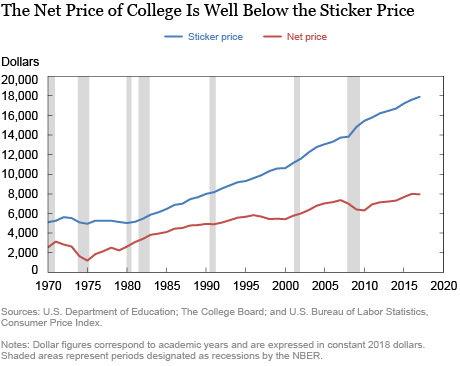

To measure the out-of-pocket cost of college, we utilize data on the average tuition and fees at four-year institutions, published by the College Board. These figures represent the “sticker price” of attending college. However, because of financial aid, many students, if not most, do not actually pay this price. The “net price” subtracts funds students receive that need not be paid back, including grants, tuition concessions, and tax benefits. Student loans are essentially a financing tool used as a way to pay for college, and so they are not considered a cost of college (interest might be considered a cost, but interest rates on student loans are frequently subsidized at below-market levels and interest is often deferred while a student is attending school). All in all, the net price is more representative of the out-of-pocket expenses paid by the average student, and tends to be less than half of the sticker price.

In the chart below, we plot the average sticker price and net price for a bachelor’s degree over time. The average sticker price increased from about $5,000 per year in the 1970s to around $18,000 today. However, net prices are much lower due to financial aid, and have tended to increase a bit more slowly than sticker prices. On average, the net price of college has increased from around $2,300 in the 1970s to about $8,000 today. Thus, if a student completed a bachelor’s degree in four years, he or she could expect to pay an average of roughly $32,000 out of pocket.

Opportunity Costs

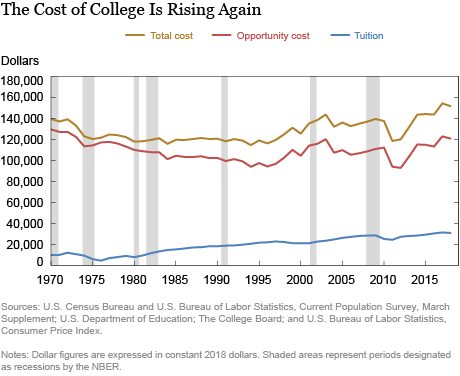

While the high and rising cost of college tuition receives considerable attention, out-of-pocket expenses prove to be only a small part of the total cost of college once opportunity costs are considered. Attending college on a full-time basis typically requires delaying entry into the labor market and forgoing wages that would be available to those with a high school education. As is common, we use the average wages earned by a high school graduate during the first four years of employment as a proxy for the opportunity cost of college, though this provides only a rough estimate since there may be inherent differences between people who go to college and those who don’t.

Using data on wages and an approach outlined in our 2014 study, we estimate this opportunity cost, shown in the chart below. Someone pursuing a bachelor’s degree could expect to forgo more than $120,000 in wages—almost four times net tuition costs. This opportunity cost has changed over time as the wages of high school graduates have fluctuated. Notably, opportunity costs fell following the Great Recession as the wages of young workers with only a high school diploma declined, but picked up markedly after 2012 as the labor market strengthened and wages increased.

Total Costs

Adding out-of-pocket expenses and opportunity costs yields an estimate of the total economic cost of a bachelor’s degree, shown in the chart above. Looking at the pattern over time, costs were flat or declining from the early 1970s through the mid-1990s, as rising tuition was offset by falling opportunity costs during this period, which were declining as the wages of high school graduates fell. Despite ongoing tuition hikes, rising costs were not really apparent until the late 1990s. By then, the wages of high school graduates had begun to climb, increasing opportunity costs and total costs until the early 2000s. Costs fell again shortly after the Great Recession before resuming their upward march in 2012. Over the past several years, rising tuition has combined with increasing opportunity costs to push up the total cost of college from less than $120,000 in 2011 to more than $150,000 in 2018—a roughly 30 percent increase in just seven years. Still, while the cost of a bachelor’s degree has in fact climbed, it is only about 10 percent higher than it was in the early 1970s.

Cost Is Only One Side of the Equation

It may be tempting to conclude that the high and rising cost of college means that obtaining a bachelor’s degree is no longer a good investment. However, such a conclusion would be premature without first considering the payoff. Our next post weighs the economic benefits relative to the costs to estimate the return to a college degree.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

Jaison R. Abel is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Richard Deitz is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this blog post:

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz, “The Cost of College Continues to Climb,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics (blog), June 3, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/06/the-cost-of-college-continues-to-climb.html.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thanks to all readers who posted comments. We respond to a number of queries in this note. Unfortunately, we don’t have any projections for the cost of college in future years. As for the current cost of tuition, $32,000 for a bachelor’s degree may seem low (our data come from the College Board, and do not include community colleges), but there are some reasons why our estimates are not as high as one might expect. – First, they don’t include room and board, which, as we note in the post, are not considered an out-of-pocket cost of college from an economic perspective. – Second, our computations are an average among both public and private schools, and tuition at public institutions is less than a third of that at private institutions. – Third, our figures represent the net price, as opposed to the sticker price, meaning they deduct financial aid received by the average student.

The authors of this article, Mr. Abel and Mr. Dietz, clearly have not gone through Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok’s recent study, “Why are the Prices So D*mn High?” That work has a very different perspective on this issue, and Helland & Tabarrok are very, very convincing. I won’t try to summarise their argument and spoil your fun in reading. But, please do read it!

A few thoughts: – $32k for a four year degree seems awfully low. Do you get this low average by taking into account tuition from attending community colleges? I would be very interested knowing about the data that goes behind the statement “cost of a bachelor’s degree… is only about 10 percent higher than it was in the early 1970s” – The opportunity cost of $120K could also consider increasing wages based on experience, so perhaps a staggered increase in wages. cheers,

College is most definitely not worth it. $120k in student debt for an Engineering degree from a state school. Graduated in 2008 when there were no jobs in my field. It took 4 years to get a job in my field that paid $20k/year less than I was expecting when I signed my loans. After working there for 4 years I got so depressed about my snowballing student debt that I could barely get out of bed and eventually got fired. And no one looks at a resume for someone who has only worked 4 out of 11 years in their field. But I can’t even file for bankruptcy. This country is pure evil.

College cost projections for 2030?