In December 2015, the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy for the first time in almost ten years and, over the following three years, it raised interest rates eight more times, increasing the target range for the federal funds rate from 0-25 basis points (bps) to 225-250 bps. To what extent are changes in the fed funds rate transmitted to cash investors, and are there differences in the pass-through between retail and institutional investors? In this post, we describe the impact of recent rate increases on the yield paid by money market funds (MMFs) to their investors and show that the impact varies depending on investors’ sophistication.

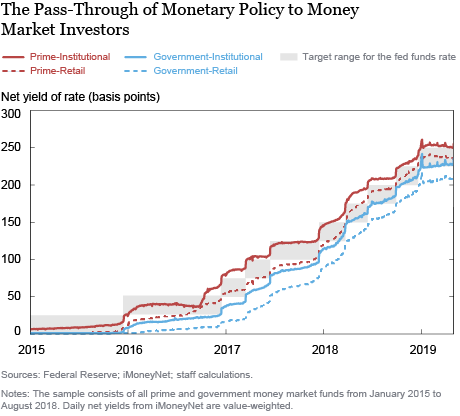

The chart below shows the net yield (the yield that MMF investors receive, net of the fees paid to the MMF) paid by the two main types of MMFs—prime (red lines) and government (blue lines)—to two different types of investors—institutional (solid lines) and retail (dashed lines); the gray area represents the Federal Reserve target range for federal funds loans. All the yields increased with the Federal Reserve target range; moreover, as the target range moved away from the zero lower bound, the gap between rates paid by prime funds and government funds widened, with the latter generally below the target range. A gap also emerged between the rates paid to institutional versus retail investors, with institutional investors generally receiving a higher yield.

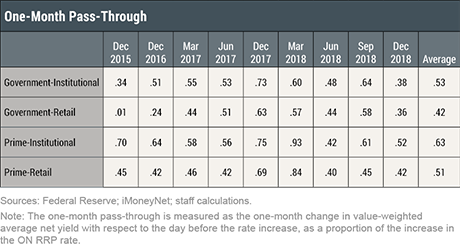

To quantify the extent of the monetary policy pass-through to MMF investors, we computed the average increase in MMF yields in the month following each rate hike as a fraction of the increase in the rate paid to lenders at the overnight reverse repurchase facility (ON RRP), as shown in the table below. On average, across all nine hikes, funds for institutional investors had the highest pass-through (63 percent for prime funds and 53 percent for government funds), while the pass-through was lower for retail investors (51 percent for prime funds and 42 percent for government funds). The difference between the one-month pass-through by institutional and retail funds was highest after the first rate hike: Whereas the one-month pass-through to institutional investors was 70 percent for prime funds and 34 percent for government funds, the one-month pass-through to retail investors was 45 percent for prime funds and just 1 percent for government funds.

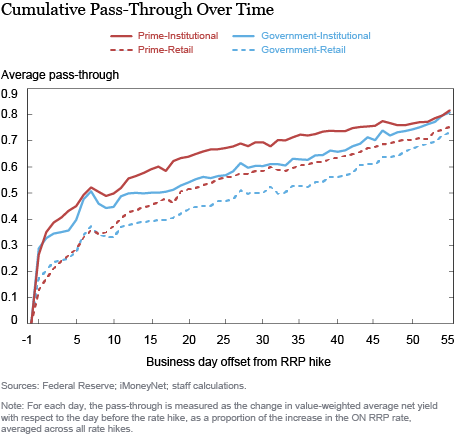

This difference in behavior of institutional and retail funds persists beyond the first month after a rate increase. The chart below reports the cumulative pass-through over time, averaged across all rate hikes: In the days just after the policy change, the difference between yields offered to institutional and retail investors is very large, but it declines over time.

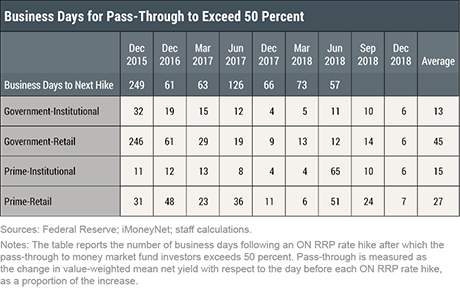

To characterize the speed of adjustment of MMF yields to increases in the ON RRP rate, we show the number of days needed for the pass-through to exceed 50 percent after a rate increase (see the table below). On average, across the nine rate hikes, the number of days for the pass-through to reach 50 percent is higher for retail than for institutional funds, in both government and prime funds. The difference between institutional and retail funds was very high after the first rate hike but has been diminishing over time.

Why Is the Pass-Through Different for Institutional and Retail Investors?

A possible explanation for the difference in the pass-through for institutional and retail MMFs is the lower financial sophistication of retail investors. This factor may have been especially material when the Federal Reserve changed its monetary policy stance after a long period of extremely low interest rates. As investors became more familiar with the new policy environment and investment opportunities, the pass-through for retail investors approached that of institutional investors. Such differences in transmission of monetary policy to different segments of the economy are key to understanding both the effectiveness of monetary policy implementation and its distributional effects.

Marco Cipriani is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Marco Cipriani is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jeff Gortmaker is a former senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gabriele La Spada is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gabriele La Spada is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Marco Cipriani, Jeff Gortmaker, and Gabriele La Spada, “The Transmission of Monetary Policy and the Sophistication of Money Market Fund Investors,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics , September 4, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/09/the-transmission-of-monetary-policy-and-the-sophistication-of-money-market-fund-investors.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Well done and fascinating work! Thank you. MMFs invest in a mix of assets including bank deposits, tri-party repo, the Fed’s reverse repurchase facility, treasury bills, and commercial paper. They pass the blended rate, less a constant fee, directly to their investors. So, the MMF passthrough effect can be broken down into a composition effect (which is not so exciting from a passthrough perspective, although revealing about substitution elasticity) and the passthrough into each asset component, where the passthrough action is most interesting. In our Jackson Hole paper*, Arvind Krishnamurthy and I showed the degree of passthrough to the underlying components of money markets. We did not have access, though, to all of the data available to you at the New York Fed. Your FRBNY colleagues Gara Afonso, Adam Biesenbach, and Thomas Eisenbach did some very helpful additional work on this.** I believe there is a lot more to be done on this important question. For example, as you point out, the relative degree of passthrough t o wholesale and retail investors could be changing. I expect, for example, more passthrough*** with the implementation of the Fed’s proposed fast payment system, provided that the technology is sufficiently open for moving funds between banks. Conflict of interest: member of the board of directors of TNB Inc. *”Passthrough Efficiency in the Fed’s New Monetary Policy Setting”, in Richard A. Babson, editor, Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future, A Symposium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 25-27, 2016, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, pages 21-102. At https://www.darrellduffie.com/uploads/policy/DuffieKrishnamurthyAugust2016.pdf **”Mission Almost Impossible: Developing a Simple Measure of Pass-Through Efficiency”, at https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2017/11/mission-almost-impossible-developing-a-simple-measure-of-passthrough-efficiency.html ***”Digital Currencies and Fast Payment Systems: Disruption is Coming,” for presentation at the Asian Monetary Policy Forum, preliminary draft, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University, May, 2019. At https://www.darrellduffie.com/uploads/policy/DuffieDigitalPaymentsMay2019.pdf

The main reason is, to me, is that institutional investors pay a much lower net expense ratio than retail investors pay. As a result, more of the rate increases are gained by institutional investors solely due to the implementation vehicle.

What bothers me, more than a little, is the people who manage institutional funds on behalf of retail investors ought to provide a veil that allows retail investors to be treated like institutions. Otherwise, I’m not sure why there are fees on retail funds. Of course as rates approached 0 there is significant compression on fees and that may well be part of this..