Two years after hurricanes Irma and Maria wreaked havoc on Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, the two territories’ economies have moved in very different directions. When the hurricanes struck, both were already in long economic slumps and had significant fiscal problems. As of the summer of 2019, however, Puerto Rico’s economy was showing considerable signs of improvement since the hurricanes, while the Virgin Islands’ economy remained mired in a deep slump through the end of 2018, though signs of a nascent recovery have emerged in 2019. In this post, we assess the contrasting trends of these two economies since the hurricanes and attempt to explain the forces driving these trends.

Background

To put the two territories’ post-hurricane economic and fiscal situations into context, it is important to understand their respective trends over the past decade. Both had been in economic slumps since around 2006; in fact, from that time until just before the 2017 hurricanes, each area had sustained a roughly 16 percent drop in total employment as well as a sizable contraction in GDP. These protracted downturns were accompanied by high and rising public debt burdens, leading to a fiscal crisis in Puerto Rico and tremendous fiscal stress in the Virgin Islands. Severe disruptions in the aftermath of hurricanes Irma and Maria exacerbated these existing conditions, leading to a sharp drop-off in both employment and economic activity in the fourth quarter of 2017. This early-2018 New York Fed press briefing provides an overview of the two economies, both before and immediately after the hurricanes.

Assessing the Recoveries

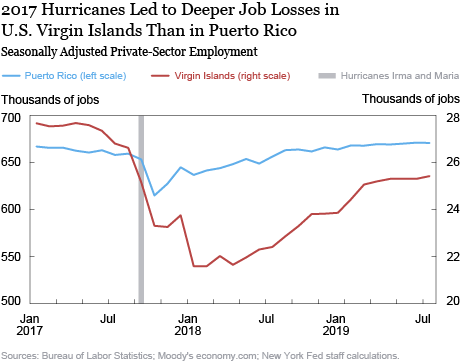

Now, just over two years after Irma and Maria, we have a clearer sense of how deep and sustained the disruptive effects of the storms were on both territories. As shown in the chart below, the Virgin Islands suffered a much steeper initial drop-off in employment (19 percent) than Puerto Rico (7 percent), and subsequently a much weaker and slower recovery. By the twelve-month anniversary of Hurricanes Irma and Maria, private-sector employment was still down 13 percent in the Virgin Islands, versus just 1 percent in Puerto Rico—thus, more than 85 percent of the initial job loss in Puerto Rico had been reversed, compared with barely over 30 percent in the Virgin Islands. In fact, as of August 2019, employment in Puerto Rico’s private sector was actually slightly above pre-hurricane levels, whereas the Virgin Islands’ private-sector job count was still down more than 3 percent, based on the New York Fed’s early benchmarked estimates—the deepest sustained post-hurricane job loss in any U.S. area, except for New Orleans following Katrina in 2005-07.

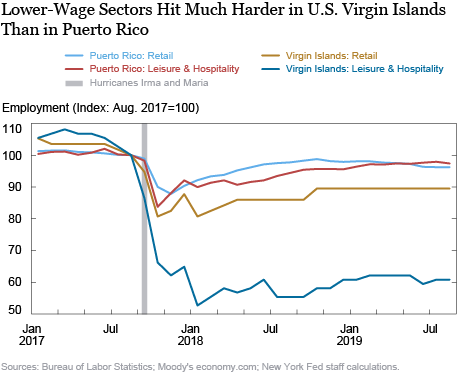

In terms of total wage and salary income, however, the divergence is far less pronounced. This stems in part from the fact that the Virgin Islands sustained exceptionally steep job losses in two major low-wage industries (retail, as well as leisure and hospitality) and job gains in two high-wage sectors (construction, and professional and business services). This sizable shift in the job mix lifted average wages and thus mitigated the decline in aggregate wages. But even within a few major industries, there were some sizable jumps in wages seen in the Virgin Islands but not in Puerto Rico—most notably in construction. This may, at least in part, reflect a steep rise in the Virgin Islands’ minimum wage.

Why Such a Divergence?

A number of factors may have contributed to the territories’ contrasting economic performance. First, the physical damage associated with the hurricanes may have been more widespread and severe in the Virgin Islands than in Puerto Rico. Two weeks before Maria, Hurricane Irma made a direct and devastating hit on St. Thomas and St. John—the northern islands of the U.S. Virgin Islands. Then Maria hit St. Croix head on, as well as Puerto Rico. It is not clear whether Puerto Rico’s much larger “footprint” (area) was a help or a hindrance—on the one hand, the southwestern and western parts of the island were on the backside of Maria and did not experience quite as much wind damage; on the other hand, many interior parts of Puerto Rico were inaccessible for a long time.

Second, and perhaps more important, are the respective compositions of the economies. While Puerto Rico’s economy is fairly diversified, with some sizable industries engaged in manufacturing, business services, and so forth, the Virgin Islands’ economy is much more based on tourism. In the aftermath of the hurricane—and as is typically the case after major local disasters—tourism-related industries like accommodation and restaurants were the hardest hit and the slowest to come back. In contrast, Puerto Rico’s professional and business services sector has seen substantial job gains since the hurricane. In fact, employment in that sector this year has been at record highs.

But it is more than just industry mix. Even within specific industry sectors, glaring contrasts exist between job trends in the two territories. In the vast majority of cases, Puerto Rico has seen significantly stronger job trends than the Virgin Islands. Many sectors—most notably leisure and hospitality and retail trade, both of which are key drivers of the Virgin Islands economy—have experienced far bigger job shortfalls in the Virgin Islands than in Puerto Rico since before the storm, as shown in the chart below.

A number of other differences may also help explain the sharply contrasting economic trends. One possible contributor is hotel capacity. As noted in this July 2018 post, there has been virtually no new hotel construction in the Virgin Islands for more than two decades, and hotels in Puerto Rico were much quicker to reopen after the hurricanes than those in the Virgin Islands. [At the time that post was written, nearly 90 percent of Puerto Rico’s hotels had reopened versus just 60 percent of those in the Virgin Islands.]

Another possible contributor is the minimum wage. While Puerto Rico’s minimum wage has remained at the federal threshold of $7.25 an hour, the U.S. Virgin Islands ratcheted its minimum wage up from $7.25 in the first half of 2016 to $10.50 as of June 2018—a 45 percent rise—with the most recent increase coming when the territory’s economy was already severely disrupted by the hurricanes. Although recent research on adverse employment effects from minimum wage hikes has been mixed, it is plausible that such hikes may have exacerbated the disruptive employment effects of a natural disaster like the one-two punch of Irma and Maria. But the steep hike in the minimum wage and its upward effect on average wages may also help explain why the divergence between the two territories was much narrower for overall wage and salary income than for the job count.

Jason Bram is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jason Bram is a research officer in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jason Bram, “U.S. Virgin Islands Struggle While Puerto Rico Rebounds,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 2, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/10/us-virgin-islands-struggle-while-puerto-rico-rebounds.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Jeffery: Thank you for your interest and your thoughtful questions. In this analysis, we focused only on employment and earnings, not the number of establishments. But I think it is almost certain that the USVI did indeed lose a larger proportion of such establishments, after the storms, than Puerto Rico. If so, the same question remains: why? Insofar as disruptions in the USVI (positively) affected Puerto Rico, it’s important to remember that PR’s economy and population are about 30x as large as the U.S. Virgin Islands’, so it’s unlikely that anything going on in the USVI would have any significant direct effect on Puerto Rico. As for the notion that some of the high-paying construction jobs may be going to workers imported from the mainland, that is indeed a possibility in both USVI and Puerto Rico—and that would cause *both* the post-hurricane earnings and employment levels to be somewhat overstated. However, to be included in the islands’ job and income counts, a worker has to be on the payroll of a local employer; contract workers from the mainland are not included. And finally the policy ratcheting up the minimum wage in the U.S. Virgin Islands was implemented long before Irma and Maria, so the storms would not have been a factor in that decision.

What percentage of Leisure and Hospitality establishments were affected in Puerto Rico vs. USVI? If the USVI lost a much larger share of these establishments than Puerto Rico, this could explain the slower recovery in USVI (remaining establishments in Puerto Rico getting more business than usual). What percentage of high-paying construction jobs in the USVI are held by USVI residents? If most of these jobs are filled by construction workers from outside the USVI, the wage impact for USVI residents may be as pronounced as the job impact. Did federal government contracts for recovery efforts require that a certain percentage of the jobs be filled locally? This is sometimes the case. If so, this could explain the decision to dramatically increase the minimum wage during an economic slump. If this is the case, it is a further indicator of the weakness of the USVI economy (dependence upon federally-mandated jobs overriding other considerations).