A key part of understanding the stability of the U.S. financial system is to monitor leverage and funding risks in the financial sector and the way in which these vulnerabilities interact to amplify negative shocks. In this post, we provide an update of four analytical models, introduced in a Liberty Street Economics post last year, that aim to capture different aspects of banking system vulnerability. Since their introduction, vulnerabilities as indicated by these models have increased moderately, continuing the slow but steady upward trend that started around 2016. Despite the recent increase, the overall level of vulnerabilities according to this analysis remains subdued and is still significantly smaller than before the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Vulnerability Measures

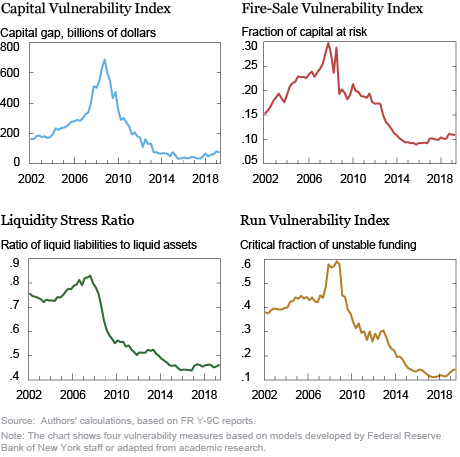

We consider the following measures that are based on models developed by New York Fed staff or adapted from academic research.

- Capital vulnerability. This index measures how well capitalized banks are projected to be after a severe macroeconomic shock. The measure is constructed using the CLASS model, a top-down stress testing model developed by New York Fed staff. Using the CLASS model, we project the regulatory capital ratio of each large banking organization under a macroeconomic scenario equivalent to the 2008 financial crisis. The vulnerability index measures the aggregate amount of capital (in dollars) that would be needed under that scenario to bring each banking firm’s capital ratio up to at least 10 percent.

- Fire sale vulnerability. This index measures the magnitude of systemic spillover losses among banks caused by asset fire sales under hypothetical stress scenarios, and is expressed as a fraction of system capital. In this New York Fed staff report, “Fire-Sale Spillovers and Systemic Risk,” we show that an individual bank’s contribution to the index predicts its contribution to systemic risk five years in advance.

- Liquidity stress ratio. This ratio captures the liquidity mismatch between a bank’s assets and liabilities during a liquidity stress scenario. It is defined as the ratio of expected cash outflows in times of stress to the size of the bank’s portfolio of liquid assets. If the ratio is high, it means that there may be insufficient liquid assets to meet expected outflows in stressful conditions.

- Run vulnerability. This measure gauges a bank’s vulnerability to runs, taking into account both liquidity and solvency. It combines a theoretical framework with projections of stress deterioration in bank capital from the CLASS model. An individual bank’s run vulnerability is the critical fraction of unstable funding that the bank needs to retain to prevent insolvency.

Trends in Vulnerability

The chart below shows how the different aspects of vulnerability have evolved since 2002, according to the four measures.

Next, we discuss developments of the individual measures in more detail.

Capital Vulnerability

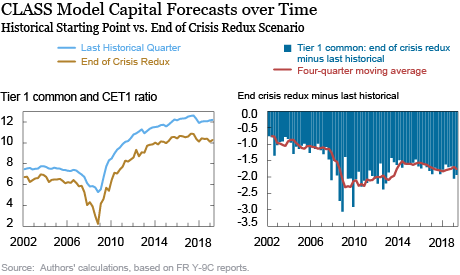

The capital vulnerability index has increased over the past year, continuing a trend of sideways or upward movement since 2016.

Movements in the capital gap reflect the combination of changes in the starting level of capital, as well as changes in the fall in capital under an adverse macroeconomic realization forecast by the model. Starting capital ratios have increased in the past year, but have not yet returned to prior levels after the fall related to the Tax Cut and Job Act in the second quarter of 2017 (see the blue line on the left panel of the chart below). The fall in capital—the difference between the starting point of the common equity tier 1 (CET1) ratio and that at the end of the crisis redux scenarios—has also increased over the past year (see the right panel of the chart below).

The evolution of the fall in capital is a way of understanding how, subject to the same scenario, bank capital is vulnerable. Although the capital fall is variable from quarter to quarter, the fall has increased in the past year (by 32 basis points), continuing an overall trend since 2014 of increasing risk should a scenario similar to that of the crisis be realized. This increase in the fall in capital arises primarily from weaker profitability relative to a year ago.

Fire-Sale Vulnerability

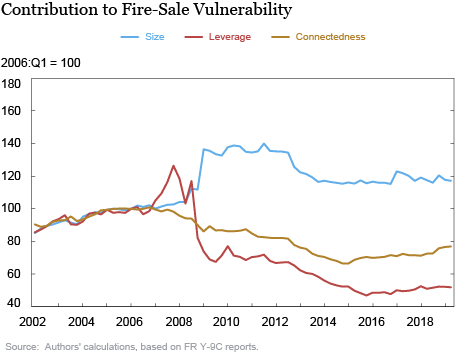

The fire-sale vulnerability index has been increasing slowly but steadily in the last three years, with a cumulative growth of 18 percent. Despite this recent climb, the level of the index remains low compared to its pre-2014 levels.

To shed some light on the reasons why the index evolves the way it does, the chart above decomposes the index into the overall size of the banking system (total assets), its leverage, and its “connectedness.” The increasing trend since 2016 can be attributed in equal parts to increases in leverage and connectedness, while the size component has remained essentially flat.

Another way to understand the index is by studying the contribution of individual asset classes to the index. The five asset classes that contribute the most as of the second quarter of 2019 are agency MBS, fed funds and repo loans, commercial and industrial loans, residential real estate loans, and consumer loans. Compared to the pre-crisis period, when residential real estate loans were considerably more systemic than all other asset classes, the model suggests no asset class stands out as particularly systemic in the recent past.

Liquidity Vulnerability

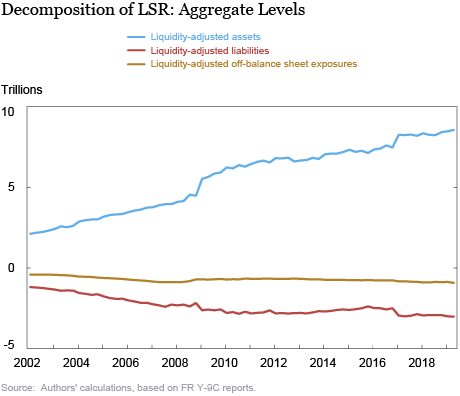

The aggregate liquidity stress ratio (LSR) has remained near all-time historical lows over the past few years. Looking at the decomposition of the LSR in the chart below, we see that liquidity-adjusted assets have risen slightly. This was accompanied by an inching down of liquidity-adjusted liabilities and off-balance-sheet items.

The LSR saw a peak in the third quarter of 2007 that was driven, to some extent, by the collapse in securitization and asset backed commercial paper markets. The LSR was improved, in part, by the Federal Reserve’s monetary stimulus programs, which drastically increased the amount of reserves in the banking system. Reserves and cash constitute a large component of liquid assets for some banks.

In part thanks to liquidity regulation, such as the liquidity coverage ratio, the largest U.S. banks are in a much stronger liquidity position, on aggregate, than at any point before or during the 2008 crisis. This is perhaps best exemplified by the fact that the LSR has remained stable, despite the removal of reserves of more than 1 trillion U.S. dollars from the banking system since 2014. While cash, of which reserves can be a large part, has fallen slightly in the most recent year, its decrease was not commensurate with the aggregate drop in reserves. Moreover, decreases in cash were countered by an increase in securities held by banks.

Run Vulnerability

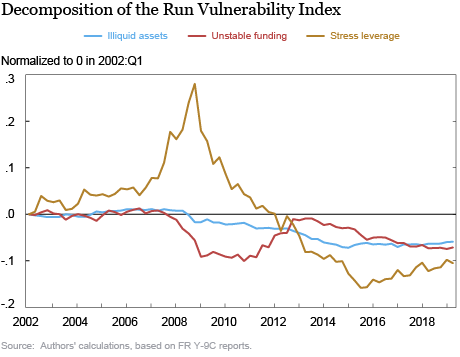

After remaining mostly flat between 2016 and 2018, the run vulnerability index has been slowly increasing over the past year. Considering the underlying components in the chart below, we see that the increase in the index was mainly due to small increases in stress leverage and illiquid assets. Stress leverage has been continuing an upward trend that started in 2015 (see the “Capital Vulnerability” discussion). The other two components, the shares of illiquid assets and unstable funding, have changed less over the past several years.

To understand better these two characteristics of the assets side and liabilities side, respectively, we consider their comprising parts in more detail. Illiquid assets are defined as the complement to liquid assets—which are composed of cash—Treasury securities and fed funds lending. In the post-crisis period, most of the variation in the liquid asset share is due to the variation in banks’ cash holdings, which mirror the level of aggregate reserves (see the “Liquidity Vulnerability” discussion). Since the beginning of the Fed’s tapering in 2014, however, the liquid asset share has stopped increasing and there has been a corresponding shift in banks’ liquid assets from cash toward Treasuries. Over the past year, the shift from cash to Treasuries has accelerated and the overall liquid asset share has started to decline slowly.

Unstable funding in this analysis is composed of commercial paper, trading liabilities, fed funds borrowing, repos, and unstable deposits, that is all deposits except for money market deposit accounts and other savings accounts as well as time deposits of less than $250k ($100k before October 2008). The decline in the unstable funding share since 2013 was not accompanied by large changes in the composition of unstable funding. While unstable funding increased in absolute terms, it was outpaced by a concurrent increase in stable funding, leading to a decline in the unstable funding share. Over the past year, this decline has slowed and it seems like the unstable funding share may have bottomed out.

Kristian Blickle is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Fernando Duarte is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Fernando Duarte is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Eisenbach is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Anna Kovner is a Vice President and Policy Leader for Financial Stability in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Kristian Blickle, Fernando Duarte, Thomas Eisenbach, and Anna Kovner, “Banking System Vulnerability: Annual Update,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, December 18, 2019, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/12/banking-system-vulnerability-annual-update.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics