Job-to-job transitions—those job moves that occur without an intervening spell of unemployment—have been discussed in the literature as a driver of wage growth. Economists typically describe the labor market as a “job ladder” that workers climb by moving to jobs with higher pay, stronger wage growth, and better benefits. It is important, however, that these transitions not be interspersed with periods of unemployment, both because such downtime could lead to a loss in accumulated human capital and because “on-the-job search” is more effective than searching while unemployed. Yet little is known about what leads workers to search for jobs while employed. This post aims to shed light on one such possible mechanism—namely, how current job satisfaction is related to job search behavior.

We use novel data from the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) Labor Market module, which has been fielded since March 2014. With this data, we document the heterogeneity in job satisfaction, analyze workers’ preferences for different job amenities, and discuss the impact of these preferences on labor market behavior.

How Satisfied Are Workers with Their Current Jobs?

To explore overall job satisfaction, we focus on the following question from the SCE:

“Taking everything into consideration, how satisfied would you say you are, overall, in your current job?”

Respondents are asked to provide a rating from 1 to 5, with 1 representing “Very dissatisfied” and 5 representing “Very satisfied.” Sixty-nine percent of employed respondents say they are satisfied (defined as somewhat or very satisfied) with their current jobs. However, respondents’ overall satisfaction with their current job differs significantly for full-time and part-time workers. While 70 percent of full-time workers report being satisfied with their current jobs, only 60 percent of part-time workers feel similarly. Some of this heterogeneity stems from the fact that part-time and full-time jobs have considerably different characteristics when it comes to compensation and nonwage amenities.

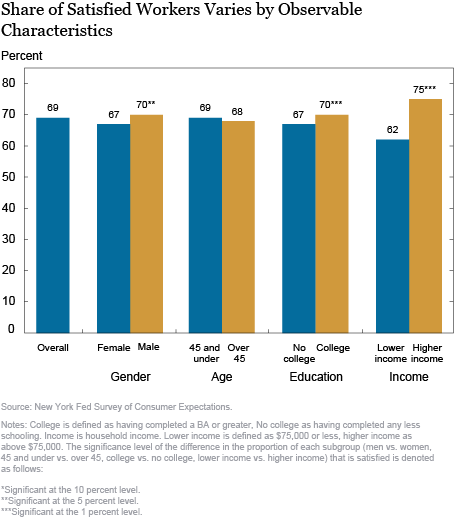

Overall job satisfaction differs across other subgroups in the sample as well (see chart below). Statistically significant differences arise by gender, education, and income group, though these effects are economically small, with the exception of the difference across income groups.

In addition to asking about overall job satisfaction, the survey elicits information about respondents’ satisfaction with specific job characteristics, namely compensation, nonwage amenities (such as benefits, maternity or paternity leave, and availability of flexible work hours), how well the job fits their experience and skills, and promotion opportunities. By analyzing responses to these questions, we can document the possible source of the difference in overall job satisfaction for different subgroups in the sample.

We observe essentially the same trends as we do for overall satisfaction, with one exception: although no significant difference exists in respondents’ overall job satisfaction across age groups, we see that younger respondents (those below age 45) are more likely to be satisfied with compensation and nonwage amenities. Aside from this disparity, the overall job satisfaction question seems to offer a good summary measure that is representative of respondents’ degree of contentment with the particular characteristics of their current jobs.

Searching for New Jobs

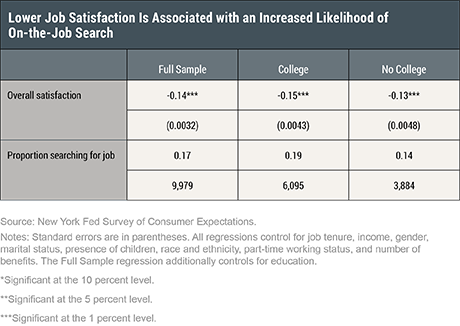

As a first step toward understanding the relationship between current job satisfaction and labor supply behavior, we examine whether job satisfaction is related to respondents’ decisions to search for other jobs. The table below shows the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates from the regression of whether the respondent has engaged in any search activities for a new job in the last four weeks on our measure of overall job satisfaction. We find that after we control for worker characteristics and other job traits, having lower job satisfaction is associated with a significantly—both economically and statistically—higher likelihood of searching for a new job. Specifically, a one unit decrease in job satisfaction (which is measured on a scale of 1 to 5) is associated with a 14 percentage point increase in the likelihood that the respondent is searching for a new job. This relationship is robust across different demographic, age, and income groups. For college graduates, there is an even stronger relationship between job satisfaction and job search.

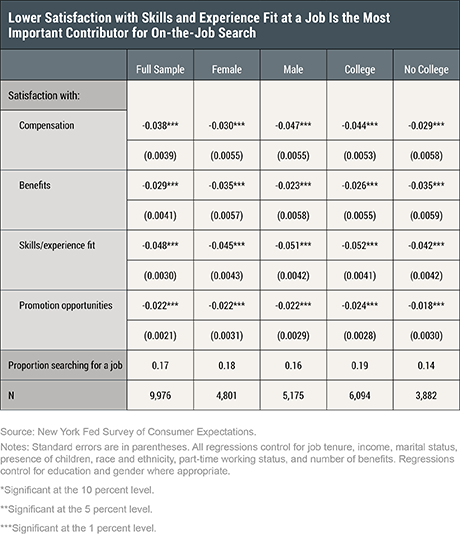

Using responses to questions about satisfaction with specific job characteristics, we can break down respondents’ preferences for job amenities and analyze the differences in how they act on these preferences in the labor market. The table below shows that respondents’ satisfaction with experience/skills fit is the most important job characteristic overall when deciding whether to search for a new job. However, the second most important characteristic differs among groups. While satisfaction with nonwage amenities is the second most important factor in the search decisions of women, satisfaction with current compensation ranks as the next most important factor for men and for college graduates.

Realized Mobility

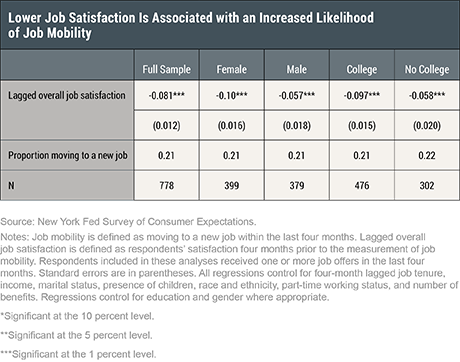

Now that we’ve learned about individuals’ preferences, the next step is to understand whether job satisfaction is an important factor for actual, realized job-to-job movements. If it is, we would expect workers with lower satisfaction to both seek and accept outside offers at a higher rate. To test this theory, we look at whether respondents with lower job satisfaction are more likely to accept the job offers they receive in the next four months, after controlling for other current job and worker characteristics. The table below presents the results from this regression. We find that even after controlling for worker characteristics and other job traits, a one unit decrease in job satisfaction is associated with an 8 percentage point higher likelihood of accepting an outside offer, conditional on receiving an offer. This relationship is both economically and statistically significant, as it corresponds to a 38.6 percent (0.081/0.21) increase in the average likelihood of accepting an outside offer.

When we consider the same regression by gender and education groups, we see that for women and college graduates, the link between overall job satisfaction and job mobility is even stronger. Interestingly, we find more muted effects of job satisfaction on men’s future likelihood of actually leaving their jobs.

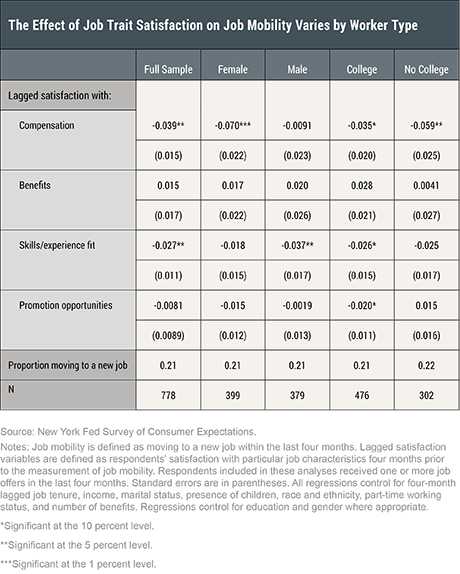

Following our earlier approach, we can again break down the relationship between overall job satisfaction and job-to-job transitions based on respondents’ satisfaction with different job characteristics. This analysis gives us important information about which job characteristics respondents value the most, as well as the drivers of job-to-job mobility for different demographic groups. Interesting patterns arise from this analysis, as shown in the table below. When we consider female respondents or respondents without a college degree only, satisfaction with compensation is the sole driver of job-to-job mobility. In the overall sample and when we consider college graduates only, however, we see that experience/skills fit at one’s current job is also an important job attribute that matters for the mobility decision, in addition to satisfaction with compensation. But for male respondents, the only current job characteristic that matters when evaluating an outside job offer is the satisfaction with experience/skills fit at one’s current job.

Conclusion

In sum, we find that how well a job matches a workers’ skills or experience is an important factor in driving search behavior. We also find that job satisfaction is highly correlated with realized mobility, because workers with a lower overall job satisfaction are around 39 percent more likely to accept outside offers, conditional on receiving an offer. These results, based on novel data from the SCE, provide another explanation for why job-to-job movements may not always lead to a wage increase. If workers with lower job satisfaction are the ones leaving their jobs, they might accept outside offers that have lower compensation and less generous nonwage amenities. In future work, we plan to continue investigating more broadly the different channels leading to job-to-job movements as well as their long-term outcomes.

Related Reading:

Gizem Kosar is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gizem Kosar is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Leo Goldman was a summer analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Kyle Smith is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Kyle Smith is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Gizem Kosar, Leo Goldman, and Kyle Smith, “Searching for Higher Job Satisfaction,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 4, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/03/searching-for-higher-job-satisfaction.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics