During moments of heightened economic uncertainty, authorities often need to decide on how much information to disclose. For example, during crisis periods, we often observe regulators limiting access to bank‑level information with the goal of restoring the public’s confidence in banks. Thus, information management often plays a central role in ending financial crises. Despite the perceived importance of managing information about individual banks during a financial crisis, we are not aware of any empirical work that quantifies the effect of such policies. In this blog post, we highlight results from our recent working paper, demonstrating that in a crisis, a policy of suppressing information about banks’ balance sheets has a significant and positive effect on deposits.

Why Might Withholding Information about Banks Be Helpful?

During normal times, regulators have long recognized that disclosure is an important tool that helps the market to discipline banks. Indeed, since the free banking era, the United States has required banks to

report summary statistics of their balance sheets on a periodic basis (through “call reports”).

In a crisis, however, theory predicts that undesirable outcomes can occur if the publication of balance sheet information induces runs on solvent banks. As a result, it may be desirable for regulators to suspend the publication of bank-specific information during a crisis so as to make banks more opaque to depositors. Such a policy action prevents depositors from being able to distinguish between banks with stronger and weaker balance sheets, reducing the chance that depositors will run on a weak, but still solvent bank (an inefficient type of bank run).

How Can We Measure the Value of Increasing Opacity?

During the bank panics of the Great Depression, policymakers tried a variety of measures to mitigate bank runs. In New York during this time, state‑level and national‑level regulators implemented different policies with regard to publishing bank balance-sheet data.

To convince “panic-stricken” households in New York that their deposits would remain liquid and safe, the New York state bank regulator suppressed bank-specific information by not collecting and mandating the publication of call report data in 1933 and 1934 for those institutions under its oversight (banks with a state charter). This policy decision effectively ended the public’s ability to observe the balance sheets of state‑charter banks for two years. In contrast, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) collected and mandated the publication of balance-sheet statistics for banks under its oversight (banks with a national charter).

Because state-charter and national‑charter banks operated side by side in New York, this difference in households’ ability to observe a bank’s balance sheet provides a unique opportunity to measure the impact of information suppression on depositors’ willingness to run on banks.

What Data Do We Use?

Our main analysis relies on balance sheet data of New York banks. Given the suspension of the call reports by the New York state bank regulator, we use an alternate source of balance sheet data provided by Rand McNally. Using this data source, we construct a semiannual panel data set on all commercial banks and trust companies in New York from 1931 to 1935. Rand McNally published information on banks’ portfolio of assets and their capital structure as of June and December of each year. Importantly, local depositors had, at best, limited access to the Rand McNally Bankers Directory because it was a subscription service directed at bankers seeking to manage their counterparty risk arising from the check clearing process. As such, we argue that the Rand McNally directory did not undo the information suppression policy of the New York state banking regulator.

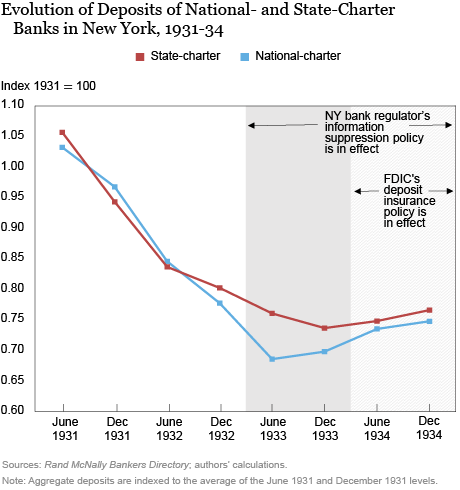

Our main results can be seen in the evolution of aggregate deposits for national‑charter and state‑charter banks in New York. As illustrated in the chart below, deposits for both types of banks mostly decline during the sample period, only beginning to increase in 1934. The change in deposits was similar for both types of banks up until 1933, when national‑charter banks experienced a sharper decline in deposits relative to state‑charter banks. We argue that state-charter banks fared better in June 1933 because of the New York state bank regulator’s policy of information suppression.

The chart also shows that aggregate deposit movements started to converge again starting in 1934. This alignment makes sense because January 1934 was when the FDIC started to provide federal deposit insurance. Having deposit insurance makes household depositors much less sensitive to bank-level information; once they are insured, depositors no longer have an incentive to monitor banks and so they pay less attention to the publication of balance-sheet statistics. As a result, the introduction of deposit insurance makes irrelevant the gains from making the balance sheets of state-charter banks more opaque, placing national‑charter and state-charter back on an equal footing.

We formalize the intuition above using formal econometric analysis. We measure the impact of the information suppression policy on deposits using a difference-in-differences approach where state-charter banks are defined as being treated and national‑charter banks are the controls. We exclude banks located in New York City as well as other financial centers, to arrive at a set of relatively homogeneous banks whose business model is to attract deposits from local households and make loans to small manufacturing and agricultural businesses.

Our first key result is that with the introduction of the New York state banking regulator’s policy of information suppression in 1933, state-charter banks attracted deposits to a greater degree relative to national‑charter banks. Reflecting the general outflow of deposits during this time period, the estimates imply that state-charter banks stemmed the outflow of deposits to a greater extent than national‑charter banks, and so end up with a level of deposits about 4 percent higher.

Our second key result is that this advantage in maintaining deposits disappeared in 1934; there is no longer a statistically significant difference in the level of deposits across state-charter and national‑charter banks. Our interpretation of this result is that the introduction of the FDIC reduced households’ incentives to monitor the set of banks in our sample to such a degree that national‑charter and state-charter banks are back to an equal footing in terms of the information environment.

Why Does This Result Matter Today?

Following the financial crisis of 2007-09, policymakers have promoted market discipline of financial institutions by enhancing public disclosure, with the goal of improving financial stability. Even with the FDIC’s deposit insurance program, public disclosure of the portfolio of assets held by banks matters because banks issue significant amounts of debt that is not insured (for example, a significant fraction of bank deposits today are not insured by the FDIC). Consequently, our results are relevant today and demonstrate there is value in having regulators suppress bank-specific information in a crisis as a way to stem runs on those banks by depositors and other types of investors.

Haelim Anderson is a senior financial economist at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

Adam Copeland is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Haelim Anderson and Adam Copeland, “The Value of Opacity in a Banking Crisis,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, March 23, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/03/the-value-of-opacity-in-a-banking-crisis.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics