As an important driver of the inflation process, inflation expectations must be monitored closely by policymakers to ensure they remain consistent with long-term monetary policy objectives. In particular, if inflation expectations start drifting away from the central bank’s objective, they could become permanently “un-anchored” in the long run. Because the COVID-19 pandemic is a crisis unlike any other, its impact on short- and medium-term inflation has been challenging to predict. In this post, we summarize the results of our forthcoming paper that makes use of the Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) to study how the COVID-19 outbreak has affected the public’s inflation expectations. We find that, so far, households’ inflation expectations have not exhibited a consistent upward or downward trend since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the data reveal unprecedented increases in individual uncertainty—and disagreement across respondents—about future inflation outcomes. Close monitoring of these measures is warranted because elevated levels may signal a risk of inflation expectations becoming unanchored.

The Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) is a monthly, internet-based survey produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York since June 2013. It is based on a twelve-month rotating panel (respondents are asked to take the survey for twelve consecutive months) of roughly 1,300 nationally representative U.S. household heads. An important feature of the SCE is that respondents receive an invitation to complete the survey on different days spread out throughout the month. This way, consumers’ expectations are captured relatively uniformly throughout the month. The SCE elicits different measures of inflation expectations. This post focuses on the short- and medium-term inflation density forecast questions in which respondents are asked to state the percent chance that the rate of inflation will fall into various bins. These density forecasts are used to calculate the three measures we focus on in this post: the individual inflation density mean (the mean of a respondent’s density forecast), the individual inflation uncertainty (measured as the interquartile range of a respondent’s density forecast), and the inflation disagreement across respondents (measured here as the interquartile range of the distribution of the respondents’ individual inflation density means).

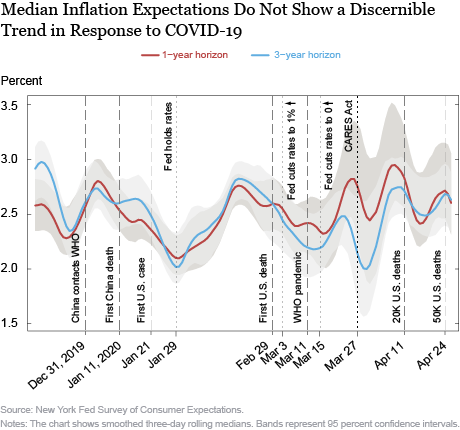

The chart below shows the smoothed daily median of the individual inflation density mean at the one-year and three-year horizons, where the median is the point at which 50 percent of respondents expect inflation to be above this level, and 50 percent below. We also added vertical bars to the chart to mark some of the key dates in the development of the COVID-19 pandemic. We distinguish health-related events (marked by long-dashed vertical lines), from policy-related events (marked by short-dashed vertical lines). The chart shows that the medians of the short- and medium-term density means have moved up and down substantially since the outbreak of COVID-19. Thus, so far, the pandemic does not seem to have had a clear upward or downward impact on this aggregate measure of consumers’ inflation expectations.

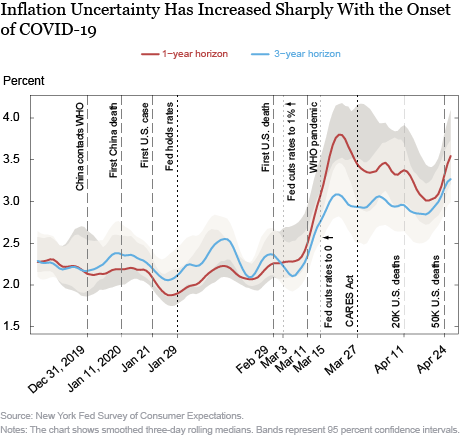

The next chart shows the smoothed daily median of the individual inflation uncertainty at both horizons. Unlike inflation expectations, this measure of inflation uncertainty exhibited a clear monotonic increase during the first three weeks of March. In fact, the sharp increase in one-year ahead inflation uncertainty is unprecedented and in March it reached levels never seen since the inception of the SCE in June 2013. After peaking toward the end of March, inflation uncertainty has remained elevated in recent weeks compared to the pre-COVID-19 period. Thus, respondents have expressed more diffused beliefs about future inflation since the beginning of the pandemic. In particular, on average, they have assigned higher probabilities to extreme inflation outcomes, such as the possibility of deflation or the risk that inflation may end up being higher than 4 percent.

It is interesting to note that inflation uncertainty in the SCE is generally higher at the three-year horizon than at the one-year horizon, simply reflecting the fact that respondents usually find it more difficult to predict inflation further in the future. In contrast, since the beginning of the pandemic, inflation uncertainty has been uncharacteristically higher at the one-year horizon. This result suggests that people are especially uncertain about the impact of the pandemic on the economy in the shorter term.

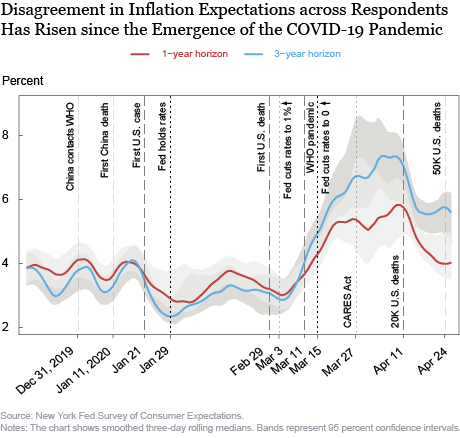

Finally, we plot in the chart below our smooth daily measure of inflation disagreement across respondents for the short- and medium-term horizons. Inflation disagreement increased steadily through the month of March, and subsided somewhat after the signing of the CARES Act on March 27. In other words, as the crisis initially progressed SCE respondents became more divergent in their inflation expectations (that is, in their density means): some respondents expected the pandemic to produce high inflation, while others expected it to yield low inflation. In particular, the proportion of respondents who think there will be deflation next year (that is, with a density mean below zero) jumped from less than 10 percent at the end of February to more than 20 percent a month later. Likewise, the proportion of respondent who expect short-term inflation to be higher than 4 percent jumped from around 30 percent to almost 45 percent during the same period.

Note also that our measure of disagreement has been higher for short-term inflation since the start of the pandemic. This is in contrast with historical trends. Indeed, SCE respondents usually disagree more about which path inflation will take in the medium term. This inversion in the term structure of disagreement may reflect the uniqueness of the impact of COVID-19 on the economy. Indeed respondents may find it difficult to agree whether the dominant short-term economic disruption will be mostly a supply or a demand shock, and in turn whether the pandemic will produce higher or lower inflation in the year ahead. Relatedly, we also see an increase in disagreement across respondents for many other variables, including for perceived layoff risk, household spending and income growth, and expected credit access conditions. Thus, it appears that respondents have very dispersed views on where the economy is headed in the months ahead.

Summing up, we find that, so far, households’ inflation expectations have not exhibited a consistent upward or downward trend since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the data reveal unprecedented increases in individual inflation uncertainty and in inflation disagreement across respondents. These changes in beliefs may in turn affect real activity, although in the current unprecedented conditions it remains unclear in what direction and by how much. Regardless, as discussed here, close monitoring of these measures is warranted because elevated levels may signal a risk of inflation expectations un-anchoring.

Olivier Armantier is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Gizem Kosar is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Rachel Pomerantz is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Daphne Skandalis is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Kyle Smith is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Kyle Smith is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Giorgio Topa is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group

How to cite this post:

Olivier Armantier, Gizem Kosar, Rachel Pomerantz, Daphne Skandalis, Kyle Smith, Giorgio Topa, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Inflation Expectations in Times of COVID-19,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 13, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/05/inflation-expectations-in-times-of-covid-19.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics