People across the world have cut back sharply on travel due to the Covid-19 pandemic, working from home and cancelling vacations and other nonessential travel. Industrial activity is also off sharply. These forces are translating into an unprecedented collapse in global oil demand. The nature of the decline means that demand is unlikely to respond to the steep drop in oil prices, so supply will have to fall in tandem. The rapid increase in U.S. oil production of recent years was already looking difficult to sustain before the pandemic, as evidenced by the limited profitability of the sector. Now, U.S. producers may have to bear the brunt of the global supply adjustment needed over the near term.

The U.S. production juggernaut was a large surprise

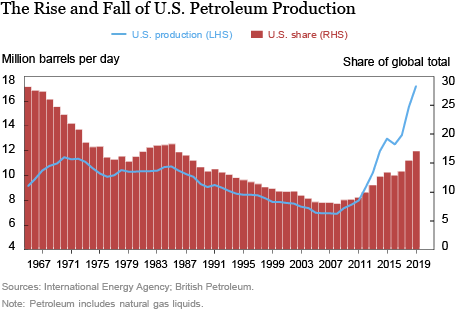

As seen in the chart below, after decades as the world’s leading oil producer, the United States saw its production move into seemingly relentless decline, falling by 40 percent from 1970 to 2005. (In line with industry practice, “oil” refers to crude petroleum plus natural gas liquids.) As U.S. production was hitting bottom, production growth in the rest of the world began to slow. Indeed, it was widely believed that the world was nearing “peak oil,” and that prices would have to move steadily higher to keep demand in line with sluggish supply growth.

Then came the fracking revolution, which allowed producers to tap previously uneconomic oil deposits. U.S. production took off beginning 2011, and was up more than 50 percent by late 2014. Producers in the rest of the world were forced to adjust to losses in market share. Pushback finally came in late 2014, when Saudi Arabia said it would no longer limit its own production to offset increases in the United States. Prices fell from over $100 a barrel in August to barely $60 a barrel by the end of the year. Production by Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq flooded the market over the course of 2015, leading to further price declines. In the new, lower-price environment, U.S. oil production growth slowed and actually fell modestly in 2016.

The impact on the U.S. crude oil industry was large enough to contribute to the overall weakness of the U.S. economy in 2015 and 2016, with reduced investment in extraction activities subtracting 0.3 percentage point from GDP growth in each of those years.

Perhaps surprisingly, however, U.S. oil production recovered in short order, despite prices staying range-bound at their new, lower level. According to the Oil Market Report published by the International Energy Agency (IEA), U.S. production rose from 13.3 million barrels a day in 2017 to 17.2 million barrels a day in 2019. At the beginning of this year, the IEA’s projection was for U.S. production to rise again to 18.3 million barrels a day. With global oil consumption stuck near 100 million barrels a day, U.S. firms were set to increase their market share by 5 percentage points over just three years.

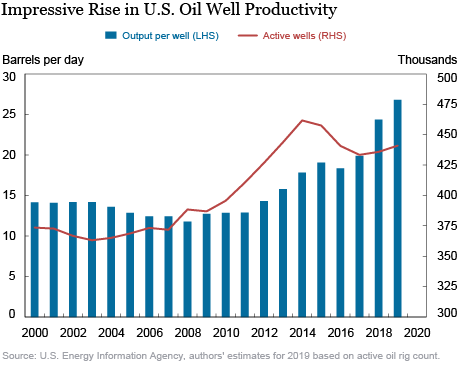

Higher U.S. production has been achieved via remarkable productivity gains. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, oil industry total factor productivity—a measure of the efficiency with which, labor, capital, and intermediate inputs are employed—was up 40 percent in 2018 relative to its level in 2014. According to our own calculations, total factor productivity saw another double-digit gain in 2019.

These productivity gains have a clear source in the technology of oil extraction. Data from the U.S. Energy Information Agency, seen in the chart below, has oil production per active rig up by roughly 50 percent from 2014 to 2019. Simply put, U.S. producers have been able to do more with less.

U.S. firms gained at the expense of others

The impact of higher U.S. crude oil production on global oil prices was moderated by developments elsewhere. U.S. oil production rose by 3 million barrels a day from 2017 to 2019, while global consumption rose by 2 million barrels a day. The global market was able to absorb the higher U.S. contribution due to output declines elsewhere. Iran saw its production fall by 1.5 million barrels a day over the period following the re-implementation of sanctions; in Venezuela, domestic turmoil lowered output by 1.0 million barrels a day. Both countries, though, are now producing at these lower levels according to the IEA and were not going to meaningfully offset further increases in U.S. production.

In short, the IEA forecast at the start of the year showed an imbalance that had to be resolved. Before the pandemic, the outlook was for global oil consumption to grow by a bit over 1 million barrels a day in 2020, mostly in China. While U.S. production was set to increase by roughly the increase in global consumption, the market would also have to absorb large expected output gains in Norway and Brazil. It would have been left to Saudi Arabia to support prices by cutting its own output—or to repeat its 2014 experiment of letting prices fall to knock back the U.S. industry.

Pandemic forces an early reckoning for U.S. producers

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a collapse in global oil demand. Currently, the IEA projects that global oil consumption will drop by 9.3 million barrels a day this year relative to 2019. However, the expected decline is not distributed equally over the year, penciled in at a stunning 29 million barrels a day in April versus the year-ago level, but then, following a projected recovery in demand, down by only 3 million barrels a day in the month of December. It is not hard to imagine a weaker recovery in oil consumption in the second half of the year and thus a larger decline for 2020 as a whole.

So how will supply fall to meet demand? OPEC countries have agreed to cut back production by 9.7 million barrels a day in the near term, which would be a major accomplishment if successful. There is, of course, no government authority to manage the U.S. contribution to the global supply adjustment, so it will be determined by the needs and actions of the firms involved. As a point of reference, applying the IEA’s projected 9 percent cut in global demand to the United States would require U.S. output falling by 1.6 million barrels a day in 2020 to bring the market into balance. The demand shock is hitting an industry that was already facing significant financial challenges. Indeed, output might end up falling much more if prices stay so much below last year’s level, which was already too low for many firms. Sharply lower production and sharply lower prices translate into a dramatic fall in revenues for the industry this year.

On our estimates, the U.S. oil extraction industry recorded negative economic profits last year, after climbing back to profitability in 2018 for the first time since 2014. (Our profits proxy follows National Income and Product Accounts [NIPA] accounting principles in measuring profits as value added less labor compensation, depreciation, taxes on production less subsidies, and interest payments. Unlike the official profits data, it also includes unincorporated businesses, which hold roughly half the sector’s capital stock.)

Looking back, the efficiency gains achieved by U.S. firms may have made them victims of their own success. Oil demand is quite price-insensitive, especially over the short run. Indeed, a representative estimate is that it might take a 20 percent price drop to absorb a 1 percent increase in supply. Recall that the U.S. output increase since 2017 has added roughly 3 percent to global supply. U.S. firms acting individually apparently reckoned that they could boost profits at current or expected future prices by expanding production. But their actions, taken collectively, worked to keep prices low enough to undermine profitability industry-wide.

Investors and industry analysts clearly see tough times ahead. Bond yields have spiked for energy companies: Since December, both investment-grade and high-yield issuers in the sector have seen spreads over Treasuries rise twice as much as spreads for nonenergy companies. And as of early April, the analysts surveyed by S&P Capital IQ expected more than half of the drilling and exploration companies they follow to record negative accounting profits this year.

The oil extraction industry is currently shrinking under low oil prices. The Dallas Fed energy survey of firms in March found big declines in oil production, capital expenditures, and employment. Data on rigs in operation shows the number at work in late April at less than half the December level.

At some point, the global economy will recover and, with it, oil consumption. Oil prices will then start experiencing upward pressure, depending on how global supply reacts. Of course, substantial higher prices than exist today will encourage U.S. firms to go back into the field. It is an industry, after all, that has a history of boom and bust cycles. Still, the pandemic is causing great short-term havoc, with steep cuts in capital spending and capacity, raising questions of how quickly U.S. crude oil production can rebound.

Matthew Higgins is a vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Klitgaard is a vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Matthew Higgins and Thomas Klitgaard, “W(h)ither U.S. Oil Production?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 4, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/05/whither-us-crude-oil-production.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics