Bitcoin, and more generally, cryptocurrencies, are often described as a new type of money. In this post, we argue that this is a misconception. Bitcoin may be money, but it is not a new type of money. To see what is truly new about Bitcoin, it is useful to make a distinction between “money,” the asset that is being exchanged, and the “exchange mechanism,” that is, the method or process through which the asset is transferred. Doing so reveals that monies with properties similar to Bitcoin have existed for centuries. However, the ability to make electronic exchanges without a trusted party—a defining characteristic of Bitcoin—is radically new. Bitcoin is not a new class of money, it is a new type of exchange mechanism, and this type of exchange mechanism can support a variety of forms of money as well as other types of assets.

Money vs Exchange Mechanism

The distinction between money and an exchange mechanism is not new to the field of payments. For example, according to a report from the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI), a body within the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), money refers to the asset that is being transferred, for example currency in your wallet. In contrast, the exchange mechanism is the way in which the asset is transferred, such as physically handing the currency to a merchant in exchange for a coffee.

It is not uncommon for Bitcoin, and cryptocurrencies more generally, to be described as a new type of money. For example, this chapter of the 2018 Annual Economic Report released by the BIS “evaluates whether cryptocurrencies could play any role as money.” Similarly, Tobias Adrian and Tommaso Mancini-Griffoli categorize cryptocurrencies as a type of money in an IMF FinTech note.

With this in mind, it is worth asking what aspect of Bitcoin is truly unique: the type of money it represents or the exchange mechanism it uses? To address this question, we propose two simple classifications, one for monies and another for exchange mechanisms. For each classification, we make use of categories that are deliberately stark. While finer subcategories might improve the classifications in some instances, it is tangential to our main message.

Three Types of Money

We divide monies into three categories: fiat money, asset-backed money, and claim-backed money. The distinction between asset-backed and claim-backed money is meant to replicate the distinction between secured claims and unsecured claims. These three categories are broadly consistent with the categories of money proposed by Adrian and Mancini‑Griffoli.

Fiat money corresponds to intrinsically worthless objects that have value based on the belief that they will be accepted in exchange for valued goods and services. A typical example is currency. The paper on which a twenty‑dollar bill is printed is worth almost nothing. But a consumer can purchase coffee by handing over that piece of paper because the barista believes that she can in turn use the latter to purchase something of value. Of course, central-bank issued currencies are different from pure fiat money due to its legal tender status. Examples of fiat money without legal tender status include Rai stones or Ithaca HOURs. And Bitcoin is just another example of fiat money.

Asset-backed monies derive their value, at least in part, from the assets backing the money. A prime example is commodity money. Gold coins are intrinsically valuable because it is possible to melt a coin and find someone who would like to use the metal for another purpose.

Finally, claim-backed monies derive their worth, at least in part, from the promise of some institution to exchange the money for something of value. For example, an (uninsured) bank deposit has value based on the promise the bank makes to exchange the deposit for currency. Non-financial firms could issue claim-backed monies as well. For example, a barista may offer a coffee in exchange for a (fully punched) loyalty card. In this instance, the loyalty card is a specialized type of money that can be exchanged for a valued item. In principle, if others believe that the barista will keep her promise to redeem the punch card in the near future, it could be used like money for other goods, as long as a sufficient number of people want the barista’s coffee.

Three Types of Exchange Mechanisms

Exchange mechanisms can also be divided into three categories: physical transfer, electronic transfer with a trusted third party, and electronic transfer without a third party. While not identical, our categories are broadly consistent with categories of exchange mechanisms described in the CPMI report mentioned earlier.

Physical transfer is intended to capture the transfer of money through a physical means, such as currency or notes. This includes the exchange of goods and services for a physical money. In the case of currency, if a consumer wants to buy a coffee with a twenty-dollar bill, he needs to physically hand it over. Similarly, he could make a payment by sending a check in the mail, which would be transported physically to the recipient, for example, to pay rent to his landlord. (Technically, a check is a payment order, rather than money. That said, endorsed checks can circulate like money.)

Electronic transfers with a trusted third party represent the vast majority of electronic payments today. These transfers involve some trusted entity responsible for making sure transfers are valid. The Fedwire Funds Service® is an example of an electronic transfer system, with the Federal Reserve System acting as a trusted third party on behalf of banks and other financial institutions transferring central bank deposits to each other. (“Fedwire” is a registered service mark of the Federal Reserve Banks.)

This brings us to the final category: electronic transfers without a trusted third party. These are exchange mechanisms where the validation of transactions is decentralized, as is the case for Bitcoin and many cryptocurrencies.

Classifying Bitcoin

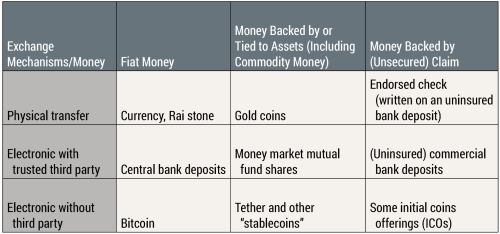

To illustrate how monies differ along these two dimensions, we have built a 3-by-3 matrix combining the types of money with the types of exchange mechanisms and, for each combination, we offer an example. The following table summarizes this exercise.

Monies transferred physically include:

- currency—a fiat money;

- gold coins—the value of which depend on the gold backing the coin; and

- checks—which are backed by the promise of a bank to exchange the check for currency.

In the United States, many bank deposits are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), so they benefit from greater protection than only the promise of the individual bank.

Monies transferred electronically with a trusted third party include central bank reserves, which in the United States can be transferred using Fedwire; money market mutual fund shares, a very liquid investment backed by assets (often Treasury securities); and (uninsured) commercial bank deposits.

Finally, monies transferred electronically without a third party include Bitcoin, which is not backed by anything; “stablecoins,” which are cryptocurrencies whose value is (in principle) tied to assets; and tokens from initial coin offerings (ICOs), for which issuers offer rights (though not necessarily legally binding) to a product or service in the future. In all these cases, the transfer of monies can be facilitated without a trusted third party. Notably, all of these examples are recent phenomena that have emerged in the post-Bitcoin era.

As is evident in the table above, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are not a new type of money. Other examples of fiat monies have existed for a very long time. The same can be said for stablecoins, which are just the latest incarnation of monies tied to the value of an asset. By contrast, the third row of the table (“electronic without third party”) did not exist before 2009. The real innovation of cryptocurrencies is that they offer a radically new exchange mechanism. This type of exchange mechanism can support the transfer of different kinds of monies; fiat money in the case of bitcoin, money backed by assets in the case of stablecoins, and even future services or products, as in the case of ICO tokens. And this type of transfer mechanism could also support the transfer of other types of assets, like CryptoKitties.

Conclusion

In this post, we have argued that Bitcoin is not a new type of money. Instead, it is more accurate to think of Bitcoin as a new type of exchange mechanism that can support the transfer of monies as well as other things. Why should we care? History provides lessons about what makes a good money as well as what makes a good transfer mechanism. These lessons could help cryptocurrencies evolve in a way that makes them more useful. But to know which lessons are relevant, it is important to be clear about what is new about Bitcoin.

Michael Lee is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Antoine Martin is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Michael Lee and Antoine Martin, “Bitcoin Is Not a New Type of Money,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 18, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/06/bitcoin-is-not-a-new-type-of-money.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Trusted intermediaries are inefficient. They’re lowering the automation potential. Furthermore it’s open for debate whether or not intermediaries should be trusted at all, especially in an increasingly digital world where the control of your data matters, and with the fact that perfect data protection doesn’t exist. Most (current) users might not care about intermediaries, companies providing services however surely care about automation and reducing operating cost. Removing intermediaries is not dictated by demand, but by economic incentives. This doesn’t mean that banks aren’t needed; banks simply need to adapt to the new technologies, like many other services in the past. bitcoin will not conveniently store itself for its users, or allow to be borrowed out of the box to invest and create growth. All in all it all depends on the amount of users of the network.

Hi Jon. Thank you for your comments. We broadly agree with you and have expressed similar views in a previous LSE blog. https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2018/02/hey-economist-what-do-cryptocurrencies-have-to-do-with-trust.html

So the real question: Is there enough demand for a “trustless” exchange mechanism like Bitcoin to justify the resources required to maintain the network? Very few people are bothered by having intermediaries. Even most activity involving Bitcoin passes through trusted intermediaries—the exchanges. Thus I would propose there is not significant demand for trustless transfers. the network survives not because of a general demand for trustless transfers, but a cult-like group of believers who are willing to keep paying with the hope of bringing in new buyers.

Very Good Topic and discussion. The problem with Crypto’s/ICO’s, is a safe place to store, we have seen Crypto exchanges close over night, theft by the exchange, frozen exchanges, embezzlement by the exchange Mgmt, with no insurance to protect the owner’s of the Crypto’s, and etc. Yes, this could happen to any currency/asset but, there is protection by Insurance/FDIC and etc. Still the Wild West. But there is a future. XRP – Ripple – which people tend not to appreciate, has its own means of exchange and use by several Financial Institutions, Money Transfer firms and etc. A system to convert money into XRP- safely, with speed, transfer XRP, between parties(banks/transfer firms) which can be immediately converted into the desired currency. Refer to Ripple for information. For me the best two currencies are Physical Gold, not paper Gold, and the $USD.