In an October post, we showed the effect of college tuition subsidies in the form of merit-based financial aid on educational and student debt outcomes, documenting a large decline in student debt for those eligible for merit aid. Additionally, we reported striking differences in these outcomes by demographics, as proxied by neighborhood race and income. In this follow-up post, we examine whether and how this effect passes through to other debt and consumption outcomes, namely those related to autos, homes, and credit cards. We find that access to merit aid leads to an immediate but temporary increase in eligible individuals’ consumption in these categories. The increase is followed by a decline in consumption and a reduction in total debt of these types in the longer term. Importantly, there are marked differences in these consumption and debt patterns across income and race groups.

Our analysis uses a nationwide data panel that links students’ educational records with their debt outcomes to understand the effect of merit scholarship programs on students’ short- and long-term financial outcomes. Our data set leverages a unique merger of the New York Fed Consumer Credit Panel (CCP) and the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC). The CCP is constructed from anonymized Equifax consumer credit reports, while the NSC contains individual-level post-secondary education records. The NSC currently covers 97 percent of all college enrollments, but its coverage rate was less complete for those attending college before the mid-1990s. We therefore limit our analysis to the 1978-88 birth cohorts for whom we can measure outcomes up to age 30.

We assume a person is eligible for merit aid if she turned 18 in a state that has a merit aid program in effect at that time. We compare the outcomes of students who were merit-eligible because of their home state and their year of birth with those of students who were not merit-eligible either because they went to college before a state’s merit aid program was implemented or because their home state never implemented such a program. We control for time-invariant characteristics of cohorts at each age as well as time-invariant characteristics of states by each age (by capturing, for example, permanent differences in state-government policies, in the educational landscape, and in labor market characteristics).

Neither the CCP nor the NSC allows direct observation of demographic characteristics, but we are able to proxy for an individual’s race and family income by observing the characteristics of the area where they first appear in our data. We use a person’s first observed zip code in the CCP as a proxy for the place they grew up. We match this zip code with the 2001 IRS zip code income and racial breakdowns from the American Community Survey (ACS) 2012-16 five-year aggregate. Using these data, we identify low-income zip codes as those that fall into the bottom quartile of mean income (where the mean income in 2001 was $24,339). We also identify predominantly Black neighborhoods as those in the top quartile of Black population share (where the average Black share during 2012-16 was 37 percent).

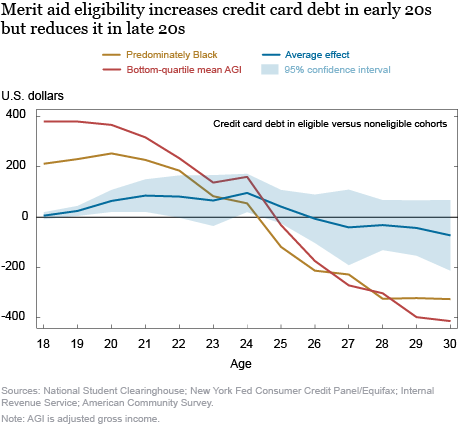

In previous work on Liberty Street Economics referenced above, we showed that eligibility for merit-based financial aid has no impact on whether students decide to go to college but leads to a lowering of their student debt burdens both during and after their expected college years. Here, we extend the analysis to investigate the impact of tuition subsidies on other debt and consumption outcomes. First, for merit-aid-eligible cohorts, we find an immediate impact on short-term spending as captured by credit card debt shown in the chart below. Our estimate indicates that this effect amounts to $100, or around 12 percent of the mean credit card balance at that age. Increased early-20s credit card spending is consistent with a direct substitution for educational expenses: some of the money not immediately spent on college tuition appears to go to other near-term consumer purchases, which could include educational materials. This compares to a reduction in student debt balance by approximately $600 at age 21. These spending effects quickly disappear as people reach their mid-20s and in fact turn slightly negative by age 30. Equally striking are the effects on credit card delinquency. By age 25, an individual belonging to a merit-eligible cohort is 1.8 percentage points more likely to have been at least 90 days delinquent on credit card debt, a 9 percent increase from the mean.

Individuals in low-income and predominantly Black zip codes see an even larger increase in credit card balances during typical college-going ages. They are possibly more credit-constrained than the average person, but access to merit aid appears to lead them to substitute more into card spending. Additionally, merit-eligible cohort members from predominantly low-income and Black areas show a significant reduction in credit card balances by 30. This is possibly owing to larger delinquencies we observe (in results not reported here) for merit-eligible cohorts when they are in their early twenties relative to ineligible cohorts originating in a similar neighborhood. Alternatively, to the extent that credit card balances represent carried-over debt, the reduction may reflect a greater ability to repay debt, or it may simply capture a lower need to borrow.

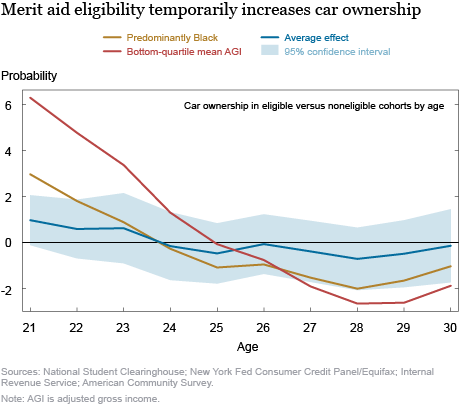

Next, we turn our attention to auto buying (as proxied by auto debt). About 85 percent of all car purchases are financed through a car loan, with the remainder representing cash purchases. Previous work indicates that the presence of merit aid induces some parents to buy cars for their college-going children. We find that individuals belonging to merit-aid eligible cohorts show an increased propensity to buy cars at the typical college-going ages, as reflected in auto loans on their credit reports, although this effect is not statistically different from zero. At age 21, individuals in merit-eligible cohorts are 1 percentage point more likely to have purchased a car (with debt financing), which translates to a 4 percent increase in the propensity to buy a car by this age. The patterns for individuals from low-income and predominantly Black neighborhoods are more striking, with merit-eligible cohort members much more likely to buy cars in their early-to-mid 20s than their peers in noneligible cohorts; notably, this effect is reversed in the late 20s. Thus, the trend shows more car-buying while in college, but possibly less buying and faster paying down of debt post-college. This pattern of substitution into car debt when the students have more cash in hand and a reversal later in life is especially prominent for individuals originating from low-income zip codes.

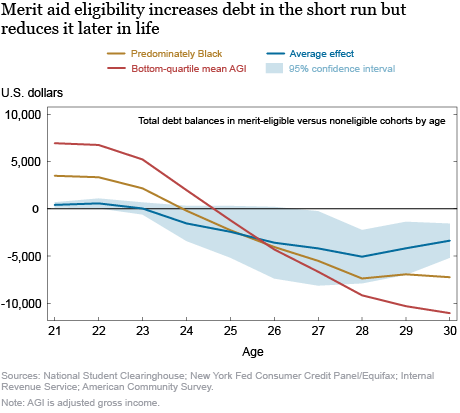

Finally, we examine individuals’ total debt balances. We define total debt as the sum of all types of debt including student, auto, mortgage and home equity line of credit, credit card, retail card, and consumer finance debt. While consistent with the previously shown debt patterns for credit card and auto loan debt, the results at later ages in the chart below are actually dominated by patterns in mortgage balances, which constitute 88 percent of individuals’ debt at age 30. Overall, we see an initial increase in total debt of merit-eligible cohort members in their early 20s, despite a reduction in their student debt balances, and a decline in their total debt burden during their late 20s. Once again, these patterns are considerably stronger for individuals originating from the low-income and predominantly Black zip codes. The alleviation of what are likely to be particularly binding credit constraints for these groups along with reduced cost of college (due to merit aid eligibility) drives consumption up even more in the early 20s, while leading to a further reduced overall debt burden in the late 20s. The decline in total debt owes not only to a decline in student debt but also reductions in mortgage, auto, and credit card debt. We are doing further research to understand these patterns.

In this post, we have investigated whether access to merit aid and the consequent reduction in student debt led individuals to substitute into other kinds of debt such as credit card, mortgage and auto. We find evidence in favor of such substitutions at college-going ages, but this increased consumption is not sustained. By age 30, overall average debt burdens are significantly lower among those belonging to merit-eligible cohorts. These patterns are much more prominent for individuals originating from low-income and predominantly Black neighborhoods. This post shows that average effects of eligibility for college subsidies hide a more complex story, with large heterogeneous impacts across different student populations.

Rajashri Chakrabarti is a senior economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

William Nober is a senior research analyst in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Rajashri Chakrabarti, William Nober, and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Do College Tuition Subsidies Boost Spending and Reduce Debt? Impacts by Income and Race,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 8, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/07/do-college-tuition-subsidies-boost-spending-and-reduce-debt-impacts-by-income-and-race.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics