Once a bank grows beyond a certain size or becomes too complex and interconnected, investors often perceive that it is “too big to fail” (TBTF), meaning that if the bank were to fail, the government would likely bail it out. Following the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, the G20 countries agreed on a set of reforms to eliminate the perception of TBTF, as part of a broader package to enhance financial stability. In June 2020, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), a sixty-eight-member international advisory body set up in 2009, published the results of a year-long evaluation of the effectiveness of TBTF reforms. In this post, we discuss the main conclusions of the report—in particular, the finding that implicit funding subsidies to global banks have decreased since the implementation of reforms but remain at levels comparable to the pre-crisis period.

What Did the TBTF Evaluation Report Find?

The TBTF reforms evaluated by the FSB include capital requirements, recommendations for enhanced supervision, and policies to resolve distressed banks. These reforms apply to systemically important banks (SIBs)—large and complex banks that are an important part of the banking sector globally. For example, globally, the share of SIBs in domestic bank assets ranges from 35 percent to 82 percent.

The FSB report finds that SIBs are more resilient than they were during the GFC. Since the implementation of Basel III regulations, they hold more capital and liquidity. Further, Basel III reforms improved the quality of regulatory capital—for example, risk-weighted capital ratios have also increased.

Increased resilience is expected to make banks safer. Indeed, the expected default risk of banks has fallen since the reforms. More important, their systemic risk—which indicates the risk a bank poses to the financial system or, alternatively, the stability of a bank during a crisis—is also lower since the GFC.

When SIBs become distressed during a crisis, their size and complexity make them difficult to resolve in an orderly manner through normal bankruptcy procedures. Thus, after the GFC, the FSB published international standards for resolving SIBs that are no longer viable as ongoing concerns. These standards comprise a mix of legal powers, policy standards, and coordination arrangements. The report finds that most authorities have comprehensive regimes in place, although their implementation remains incomplete in many countries. Moreover, the largest SIBs—global systemically important banks, or G-SIBs—in advanced economies have met international standards for maintaining sufficient equity and debt to absorb losses and to recapitalize the bank without taxpayer support in a resolution.

In spite of progress, the report finds that gaps in resolvability remain. For example, few authorities have signed institution-specific cross-border cooperation agreements, which are necessary given that SIBs have global footprints. In addition, public funds continue to be used on occasion to support SIBs experiencing financial difficulties. Finally, SIBs remain complex, with more than 1,000 subsidiaries on average spread across more than forty jurisdictions—most outside the home country—thus potentially impeding the ability of supervisors to resolve failing SIBs.

Have Implicit TBTF Subsidies to Global Banks Decreased?

If SIBs are viewed as likely to be bailed out, they can issue debt and equity at a discount to the fair market price, thus receiving an implicit funding subsidy that, in turn, creates a competitive disadvantage for non-SIB firms. If TBTF reforms are viewed as credible by market participants, then the implicit subsidy to SIBs should decrease. The FSB evaluation used different ways to estimate this implicit subsidy, but in this post we focus on one method based on a New York Fed study. Details of all the methods used are provided in the technical appendix to the FSB report.

Below, we first introduce the key concept of a TBTF risk factor, then use this factor to estimate the implicit subsidy to SIBs and how the subsidy varies in different regions of the world.

Systemic risk premium. A key concept used to estimate the implicit subsidy is the TBTF risk factor, which is based on the idea that large financial firms with a higher probability of bailout are considered less risky and so have lower equity returns in expectation. Empirically, the TBTF factor is constructed by taking a short equity position on the largest financial firms and a long equity position on smaller (but still very large) financial firms. The returns to this factor may be interpreted as the systemic risk premium—the additional compensation that investors require to hold less systemically important firms.

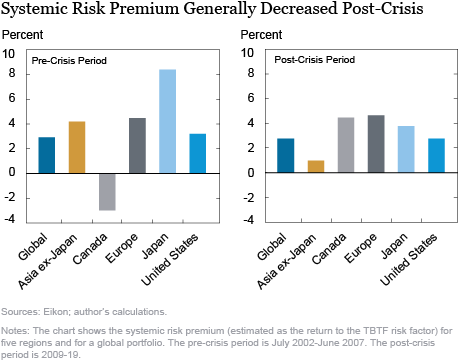

The chart below shows estimates of the systemic risk premium using equity returns data of banks from Asia (excluding Japan), Canada, Europe, Japan, and the United States. The global portfolio pools data from all five geographies. In the pre-crisis period (June 2002 to July 2007), the systemic risk premium is positive for all regions except Canada. It decreases in the post-crisis period (2009-19) for all regions except Canada and Europe. Europe may be an exception because its post-crisis period includes a second crisis event—the European debt crisis of 2011. Apart from these cases, it appears that investors require less compensation for bearing systemic risk since the GFC.

Implicit Funding Subsidy to SIBs. In order to estimate the implicit subsidy to SIBs, we consider the exposures of SIBs and other large non-SIB banks to the TBTF risk factor. Since SIBs benefit when they are perceived to be TBTF, they should have a lower TBTF risk exposure than non-SIBs. This differential exposure is a measure of the subsidy to SIBs. Our methodology accounts for the systematic risk of large banks, or how much their returns co-move with the market return. This is important because large banks are expected to have large systematic risk, which should be separated out when estimating their systemic risk.

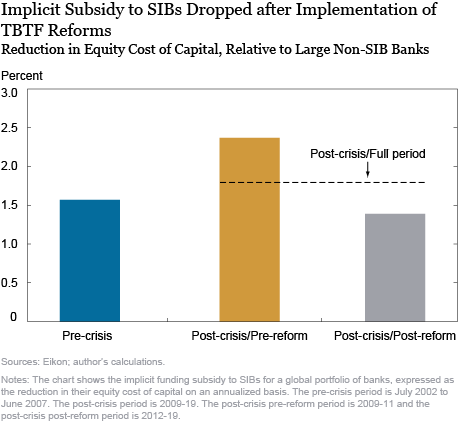

In the chart below, we show the implicit TBTF subsidy for the global portfolio of banks, expressed as a lower equity cost of capital for SIBs relative to non-SIB large banks. The implicit subsidy was 1.57 percent annually in the pre-crisis period and 1.80 percent in the post-crisis period. However, there was a shift in subsidies during the post-crisis period around the implementation of TBTF reforms in 2011. We find that the implicit subsidy actually dropped from 2.37 percent before reforms were implemented to 1.37 percent since then. Market prices thereby imply lower subsidies to SIBs than before reforms, although we cannot establish causality (since many other changes also occurred during this time).

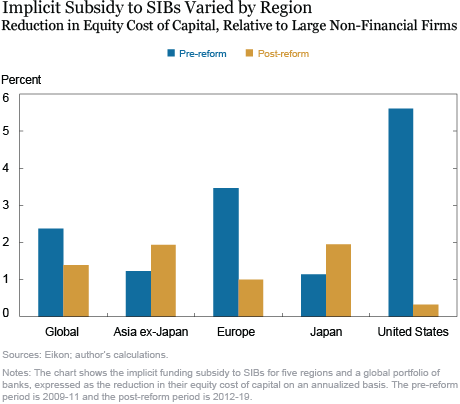

Regional Variations in Implicit Funding Subsidy to SIBs. As TBTF reforms were implemented differently in different regions of the world, changes in implicit subsidies since reforms may also vary by region. In the chart below, we show the implicit subsidies for four regions and the global portfolio. Due to data issues, the implicit subsidy to SIBs is estimated relative to large non-financial firms (instead of large non-SIB banks, as before) and Canada is excluded. The chart indicates considerable regional variation in the evolution of the subsidy, with post-reform reductions in implicit subsidies for Europe and the United States, but not for Asian countries. This dynamic is consistent with the views of credit rating agencies that the credibility of resolution regimes is greater for Europe and the United States, as described in Annex F of the FSB’s evaluation report.

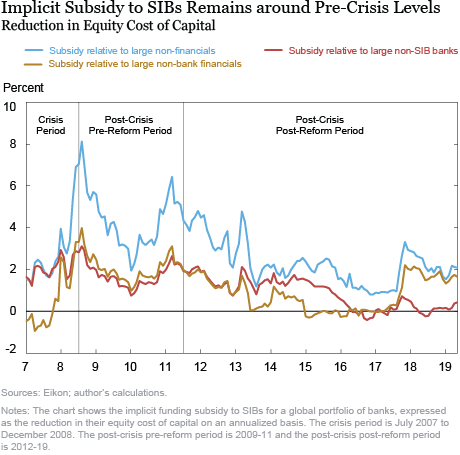

Trends in Implicit Subsidies to SIBs in Recent Years: The chart below shows the evolution of implicit subsidies to SIBs for the global portfolio, relative to three other bank groups: large non-SIB banks, large non-bank financials and large non-financial firms. For all three comparisons, the implicit subsidies have consistently decreased since their peak during the GFC, except for a second smaller peak around 2011 when the European debt crisis occurred. However, the chart also shows that the magnitude of the implicit subsidy remains at levels comparable to those before the GFC.

Looking Ahead

We have shown that implicit subsidies to SIBs have generally declined since 2012, albeit with some regional variations. While the FSB’s evaluation does not currently cover market developments since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, they will be taken into account when the report is updated in 2021. It will be interesting to see whether the implicit subsidy has changed as authorities across the globe have stepped up their economic support following the onset of this new crisis.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Asani Sarkar, “Did Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms Work Globally?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 30, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/09/did-too-big-to-fail-reforms-work-globally.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Hi Brian. Thanks for your comments. The TBTF reforms “worked” in the sense that average funding subsidies are statistically lower post-reform relative to pre-reform. However, if your point is that implicit subsidies are not, on average, statistically zero during the post-reform period, that’s also true.

Thanks Asani. However, perhaps the headline takeaway is that the changes have NOT worked. While the TBTF subsidy has been reduced, the fact that it still exists is an indication of this fact. If you truely want market discipline to work and to be able to say with confidence that no institution is TBTF, then the sign on the subsidy metric needs to flip.