“Arbitrageurs” such as hedge funds play a key role in the efficiency of financial markets. They compare closely related assets, then buy the relatively cheap one and sell the relatively expensive one, thereby driving the prices of the assets closer together. For executing trades and other services, hedge funds rely on prime brokers and broker-dealers. In a previous Liberty Street Economics blog post, we argued that post-crisis changes to regulation and market structure have increased the costs of arbitrage activity, potentially contributing to the persistent deviations in the prices of closely related assets since the 2007–09 financial crisis. In this post, we document how post-crisis changes to bank regulations have affected the relationship between hedge funds and broker-dealers.

The Relationship between Hedge Funds and Prime Brokers

Hedge funds rely on prime brokers and broker-dealers for a slew of services, such as trade execution, the extension of leverage, securities lending, and account centralization of cash and securities. Consolidation of the banking system over time has led to the largest broker-dealers becoming part of bank holding companies and therefore subject to bank regulations. In an update to our Staff Report, we find specific evidence that post-crisis regulation has affected the match between broker-dealers and their clients. This evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that regulations affecting incentives for banks to take on leverage pass through to their hedge fund clients and thereby increase the overall “limits-to-arbitrage” in leverage-dependent arbitrage trades.

We use data from Form ADV, which is an annual regulatory filing required by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for investment advisers. Form ADV data provides us with a repeated panel of hedge fund-prime broker pairs. These pairings enable us to study how the choice of prime brokers for a given hedge fund changes over time, including the probability of new match formation and the persistence of existing matches.

The Impact of the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR)

We focus on key Basel III banking regulations that became active in 2014. In particular, the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) requires that large banking organizations hold capital against their total leverage exposure—including on-balance sheet assets and off-balance sheet assets and exposures. Our hypothesis is that these regulations incentivize banks and their broker-dealer subsidiaries to be wary of their balance sheet size and hesitant to provide balance sheet space to hedge fund clients. We expect hedge funds to adjust by splitting their business across a larger number of prime brokers. Because the regulations are more stringent for larger and more systemic institutions, we expect the effects to be stronger for prime brokers affiliated with global systemically important banks (G-SIBs).

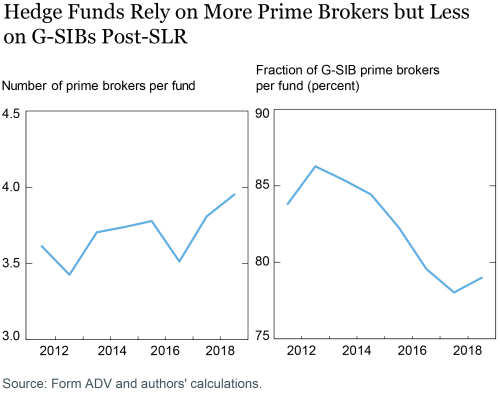

The next chart shows the average number of prime brokers reported by hedge funds over our sample period, as well as the average share of those prime brokers that are affiliated with a G-SIB. We see a first indication of the changing relationship between hedge funds and G-SIB prime brokers, with the average number of prime brokers used increasing and the share of G-SIB prime brokers declining over time.

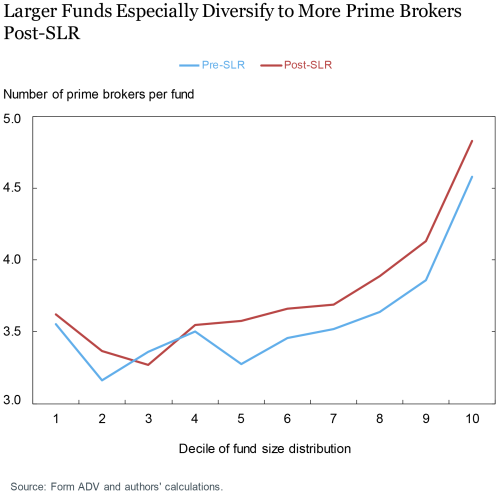

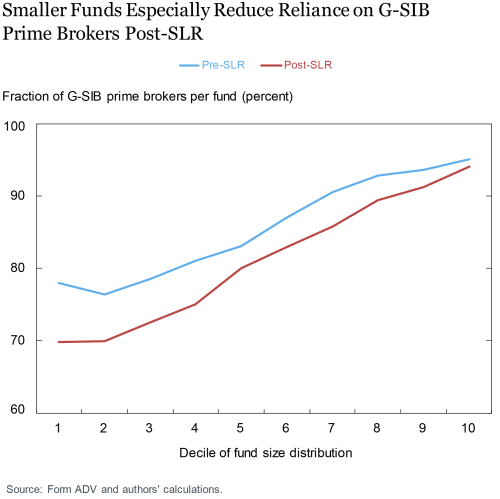

However, the hedge funds in our sample vary considerably in terms of size so we explicitly study effects for different types of funds. We split our sample into a pre-SLR period (2011–13) and a post-SLR period (2014–18), indicating the periods before and since the implementation of the SLR. We then compare within each decile of the distribution of fund size (gross asset value). On average, the smallest 10 percent of funds (1st decile) have gross assets of $1.9 million pre-SLR and $2.2 million post-SLR while the largest 10 percent have $4.1 billion pre-SLR and $5.6 billion post-SLR.

Hedge-funds Diversify to More Prime Brokers Post-SLR and the Effect Is Stronger for Larger Funds

The next chart shows the average number of prime brokers per fund for each fund size decile. Larger hedge funds tend to use more prime brokers overall and the chart shows that larger hedge funds also increased their prime brokerage relationships more post-SLR. Hedge funds splitting their business amongst more prime brokers post-SLR is consistent with the hypothesis that funds are under pressure from their brokers to economize on balance sheet space with larger funds under more pressure than smaller funds.

Hedge Funds Rely Less on Prime Brokers That Are More Constrained by the SLR but the Effect Is Weaker for Larger Funds

The next chart shows the average fraction of a hedge fund’s prime brokers that are affiliated with a G-SIB, for each fund size decile. Overall, hedge funds reduce their reliance on G-SIB prime brokers. However, for larger hedge funds, which are more reliant on G-SIB prime brokers, the effect is weaker than for smaller hedge funds. The reduced reliance on G-SIB prime brokers after the introduction of SLR is consistent with our hypothesis that the more constrained prime brokers exert more pressure on their hedge fund clients. The weaker effect for larger hedge funds is consistent with larger funds being more dependent on services that only a large G-SIB prime broker can provide.

In our Staff Report, we investigate these trends more formally using regressions where we can control for additional fund and prime-broker characteristics. We also consider the probability of a relationship at the level of each broker-fund pair and study both the probability of new relationships forming as well as the persistence of existing relationships. Consistent with a shift away from relying on G-SIB prime brokers, we find that fewer new relationships are formed each year in the post-SLR period and that this effect is stronger for G-SIB prime brokers. Further, existing relationships are more persistent, suggesting a more specialized match in each broker-fund relationship, but this effect is weaker for G-SIB prime brokers and large hedge funds.

Summing Up

Taken together, our results suggest a pass-through of regulation from the directly affected sector to other parts of the financial system, such as hedge funds, that rely on the regulated sector for leverage as well as funding, execution, and clearing services. This is important since it affects the ability of hedge funds to fulfill their role as arbitrageurs contributing to the functioning of the financial system. Recognizing these externalities, regulators temporarily excluded U.S. Treasury securities and deposits from the SLR calculation in the wake of Treasury market dislocations in early March 2020 “to allow bank holding companies, savings and loan holding companies, and intermediate holding companies subject to the supplementary leverage ratio increased flexibility to continue to act as financial intermediaries.”

Nina Boyarchenko is an officer in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Thomas Eisenbach is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Pooja Gupta is is a senior associate in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Or Shachar is a senior economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Peter Van Tassel is an economist in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Nina Boyarchenko, Thomas M. Eisenbach, Pooja Gupta, Or Shachar, and Peter Van Tassel, “How Has Post-Crisis Banking Regulation Affected Hedge Funds and Prime Brokers?” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 19, 2020, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2020/10/how-has-post-crisis-banking-regulation-affected-hedge-funds-and-prime-brokers.html .

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics