While policymakers around the world have aggressively and swiftly reacted to the common negative economic shock from COVID-19, the timing and forms of policy responses in the economic recovery stage may be more geographically differentiated. The range in policy responses, along with variations in the financial health of banks, likely will affect the flow of international credit through global banks. In this post, we ask whether, based on historical precedent, global banks are likely to provide additional support to the economic recovery in the locations they serve.

Unprecedented Policy Reactions to the Pandemic

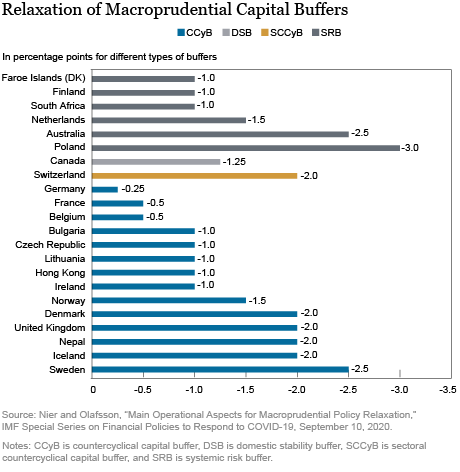

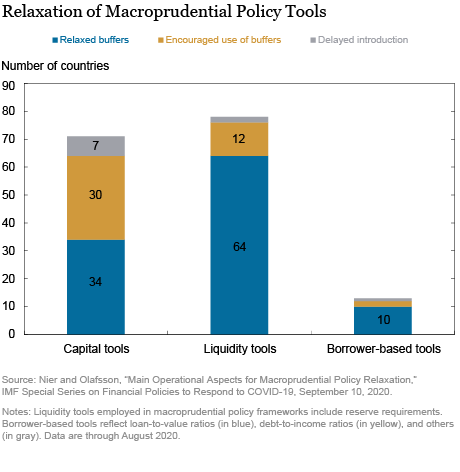

In response to the global economic decline triggered by COVID-19, authorities applied a variety of monetary, fiscal, prudential, and regulatory tools. Among these, macroprudential policy tools pertaining to bank balance sheets were loosened, as were some borrower-based tools as detailed by Nier and Olafsson (2020) (see the first chart below). Bank capital buffers were relaxed to support credit provision. Macroprudential capital buffers—including the countercyclical buffer (CCyB), sectoral countercyclical capital buffer (SCCyB), domestic stability buffer (DSB), and systemic risk buffer (SRB)—expressed as a percentage of risk-weighted assets, were reduced by between 25 basis points and 300 basis points across countries (see the second chart below). Additionally, concentration limits have been relaxed, which place a maximum on the parts of a bank’s relevant asset portfolio that can be dedicated to specific borrowers. Relaxation of borrower-based tools has included allowing higher loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-to-income ratios for households and small businesses experiencing temporary financial distress. Fiscal guarantee schemes supporting the real economy also were used extensively, delaying or moderating loan losses on bank balance sheets.

Once economic recovery is well underway, the attention of governments will turn to the progressive normalization of policies, to ensure an appropriate degree of resilience against future shocks. However, because of differences in the progress toward recovery in the broad economy and in particular sectors, this policy normalization is likely to be less synchronized globally than the initial policy loosening. Moreover, looking across countries, domestic banks are likely to emerge with different levels of balance sheet strength. Regulators need to decide on when and to what extent depleted capital buffers need to be restored. If large credit losses materialize, the domestic banking sector might in response focus on rebuilding capital. This, in turn, can temporarily weaken the ability of domestic banks to support domestic growth and recovery.

Will Spillovers through Global Banks Support Local Recoveries?

Historically, international capital flows through global banks respond to changes in policy measures. What might these responses look like following the pandemic? Foreign banks could contribute to inflows into economies and thereby partly offset the weakened ability of domestic banks to provide lending and to support recovery. Such positive spillovers in support of growth are stronger when global banks are better capitalized and have a more robust liquidity position. However, if tighter capital requirements restrict financing flows from global banks, domestic policy may face larger trade-offs between economic growth and financial stability.

In addition, the type of prudential measure matters. Suppose policy focuses on addressing the risk of excessive mortgage lending by tightening borrower-based measures such as LTV ratios. Despite the pandemic, as real estate prices have risen in many countries even during the pandemic, this might not be an unlikely scenario. In this case, authorities may want to restrict lending into overheated domestic markets by both domestic and foreign banks.

These examples indicate that spillover effects of prudential measures on cross-border lending can be positive or negative. To adequately assess spillover effects, the type and intensity of the prudential tools applied and the characteristics of the lending institutions have to be taken into account.

Recent research informs how asymmetric recoveries and normalization of policy across countries can induce shifting patterns of international lending through banks. The International Banking Research Network (IBRN) organized a cross-country evaluation of prudential policy spillovers through global banks. It consisted of research by fifteen individual country teams as well as two cross-country studies. The researchers worked in close coordination with comparable data and methods. This work utilized a new IBRN database on prudential instruments—jointly built by IBRN, the Federal Reserve board, and the International Monetary Fund—covering sixty-four countries with quarterly data from 2000 to 2018. The joint research effort’s main conclusions are summarized by Buch and Goldberg (2017). They argue that spillovers through lending growth cannot be ignored: spillovers are significant in one-third of the seventeen studies and vary across prudential instruments and banks. For example, well-capitalized banks for which tighter prudential requirements are less binding tend to expand their markets shares and lend more than weaker banks.

Insights into the underlying mechanisms can by drawn from country studies. For example, studies of German and U.S. banks show that global banks expanded lending in their home locations when foreign capital requirements were tightened (Berrospide, Correa, Goldberg, and Niepmann 2017; Ohls, Pramor, and Tonzer 2017). German banks’ loan growth abroad tended to contract; for U.S. banks, the reaction varied across types of policy instruments. Both studies found that lending by the hosted affiliates of foreign banks (that is, foreign bank branches in the host country) did not change significantly when the foreign parent country tightened capital requirements. For banks from both countries, the type of policy change matters: for example, global banks contracted lending to foreign countries that raised local reserve requirements, while they did not react much to changes in LTV ratios or concentration ratios abroad.

Changes in prudential instruments can also shift market shares between global and domestic banks. Studies of Canadian, French, Italian, and Dutch banks point towards a positive spillover effect: foreign lending growth tended to increase as prudential instruments abroad tightened (Bussière, Schmidt, and Vinas 2017; Caccavaio, Carpinelli, and Marinelli 2017; Damar and Mordel 2017; Frost, de Haan, and van Horen 2017). Thus, foreign banks gained market share during an episode of tighter requirements, either because they were not directly affected by the stricter regulations or because the regulations were less binding. For example, well-capitalized banks may have been used the opportunity to expand their international presence when other countries increased capital ratios constraining the activities of local banks. Some of the positioning and tendencies might be sensitive to the organizational form of country global bank exposures to foreign locations.

Generally, better-capitalized banks tend to be less flighty lenders and are able to bear higher risks (Avdjiev, Gambacorta, Goldberg, and Schiaffi 2020). This prior investment in strengthening the ability of banks to withstand strains as well as the extensive policy measures to dampen the impact of the global economic shock made sudden stops in banking capital flows during the pandemic more limited than initially feared for most countries.

Interaction between Prudential Policy and Monetary Policy

Tighter prudential measures can hamper the transmission of looser monetary policy, which is a reason why the macroprudential stance was relaxed in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. Prudential policy can allow monetary policy to be more accommodative than it would otherwise be the case: In the absence of macroprudential tools that address risks to financial stability, monetary policy may need to be excessively restrictive if it takes side effects on financial stability into account.

Macroprudential policy might interact with monetary policy through activities of global banks. In an IBRN project Bussière et al. (2020) summarizes six studies focusing on how macroprudential policy affects the transmission of monetary policy and the propagation of shocks across borders. The studies were jointly conducted by eleven central banks and international organizations. Among these studies, Avdjiev, Hardy, McGuire, and von Peter (2020) take a cross-country perspective, using the Bank for International Settlements’ international banking statistics, to distinguish the role of home and host factors in assessing prudential and monetary policy spillovers. The results indicate that the magnitude as well as the sign of the effects of prudential measures can depend on the nature of the measures. They also find that bank characteristics matter: the size of the bank (its status as a global systemically important bank [G-SIB], specifically) plays a key role in the transmission of domestic monetary policy and its interaction with macroprudential policy in recipient countries.

What to Watch for

Policy spillovers through global banks are shaped by bank characteristics, the macroeconomic environment, and by the type of policy instrument. Numerous regulatory and coordination issues are raised by the response of global banks to changes in policy, as discussed by Buch, Bussière, and Goldberg (2021). It is important to monitor these responses for a better understanding of how policies interact with banks’ ability to support economic recovery. This monitoring should make use of the extensive infrastructures and institutions that have been put into place. It can profit in terms of access to microdata, stress testing frameworks, methodological improvements, networks of international researchers, and established modes of cooperation among national authorities.

Claudia M. Buch is vice president at Deutsche Bundesbank.

Matthieu Bussière is a director at Banque de France.

Linda Goldberg is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Linda Goldberg is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Claudia M. Buch, Matthieu Bussière, and Linda S. Goldberg, “Will Capital Flows through Global Banks Support Economic Recovery?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/03/claudia-m-buch-matthieu-bussière-and-linda-s-goldberg-while-policymakers-around-the-world-have-aggressively-and-s.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

I believe that the case of Italy is extremely interesting: in addition to the investments that will be made when (and if) the EU-NGEU plan will be activated (the guidelines are very stringent), and the funds (EU-SURE) already allocated to support workers damaged by the pandemic, the European Central Bank has allowed the Italian government a truly significant deficit. There is probably no longer a problem of repayment of governments’ public debt, which is now permanently part of the assets of central banks, and which allows for an increase in monetary aggregates.