It is common during recessions to observe significant slowdowns in credit flows to consumers. It is more difficult to establish how much of these declines are the consequence of a decrease in credit demand versus a tightening in supply. In this post, we draw on survey data to examine how consumer credit demand and supply have changed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The evidence reveals a clear initial decline and recent rebound in consumer credit demand. We also observe a modest but persistent tightening in credit supply during the pandemic, especially for credit cards. Mortgage refinance applications are the main exception to this general pattern, showing a steep increase in demand and some easing in availability. Despite tightened standards, we find no evidence of a meaningful increase in unmet credit need.

Demand and Supply of Household Credit during a Recession

How would one generally expect credit flows to consumers to change during a recession? To the extent that households perceive declines in income and wealth as permanent, they may lower current consumption and demand for debt. Similarly, an increase in uncertainty can depress consumption and increase precautionary or “buffer-stock” saving, reducing demand for credit. On the other hand, during recessions households may optimally respond to a temporary negative income shock by drawing on new and existing credit in order to smooth consumption.

On the supply side, access to credit may become more difficult during recessions due to a rise in lender risk aversion or a reduction in collateral values. Lenders may be concerned that a recession and higher unemployment could trigger a sharp rise in loan defaults, and this concern may cause them to tighten credit standards. With lenders requiring higher credit scores, more income documentation, and reduced credit limits on new and existing loans, households may find it harder to obtain credit when they most need it.

While we expect these factors to play similar roles in the current recession, the pandemic and the public health and policy responses resulted in an economic downturn with different characteristics and dynamics than prior recessions. The recession was unique in the speed with which it took hold, the types of workers it affected, and the nature and size of the policy response. In an economy with reduced consumption opportunities (especially services) due to lockdowns, a huge decline in employment was accompanied by a steep decline in spending, but also a jump in the personal savings rate to a record high, as personal income surged in response to policy measures.

Using the SCE to Measure Demand for Credit

Our analysis draws on data from the Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) Credit Access Survey. The survey has queried respondents every four months since October 2013 about their experiences and expectations of applying for and obtaining credit. Our data differ from existing data sources in several important ways. First, unlike existing sources such as the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS), our survey captures realized and expected credit demand as reported by consumers instead of lenders. Second, we measure credit applications and rejections separately for different types of consumer loans, including mortgages, auto loans, and credit cards. Third, besides realized and expected credit demand, we identify “discouraged credit seekers”—respondents who report not applying for credit over the past twelve months despite needing it, because they believed they wouldn’t be approved.

In this post, we introduce a new, more forward-looking gauge of unmet need based on a new measure of latent credit demand. Specifically, starting in October 2016 we began asking respondents for the probability that they will apply for credit over the next twelve months if their application is guaranteed to be approved. Our new measure of unmet need is then defined as the difference between their answer to this question and their reported unconditional probability of applying over the next twelve months.

Application and Rejection Rates

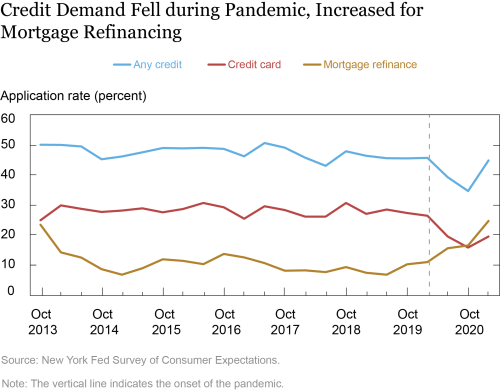

The overall share of respondents who reported applying for any type of credit over the past year shows a v-shaped pattern after the onset of the pandemic, as shown in the chart below. After the share of those who reported applying fell from 45.6 percent in February 2020 to 39.2 percent in June and to a series low of 34.6 percent in October, we see a robust rebound in February 2021 to an application rate of 44.8 percent, just below its pre-pandemic value. We see a similar pattern for credit card application rates, which fell from 26.3 percent in February 2020 to 15.7 percent in October, though with a smaller rebound in February 2021 to 19.4 percent, still well below pre-pandemic levels. Requests for credit card limit increases (not shown) evolved comparably. Auto loan and mortgage application rates (not shown) were relatively more stable and in February 2021 were just above their year-ago levels.

The big outlier in these reported trends is a dramatic increase among mortgagors in mortgage refinance applications during the pandemic, with many mortgage loan borrowers taking advantage of low interest rates. In February 2021, 24.6 percent of mortgagors reported applying for a refinance over the past twelve months, compared to only 10.8 percent a year earlier.

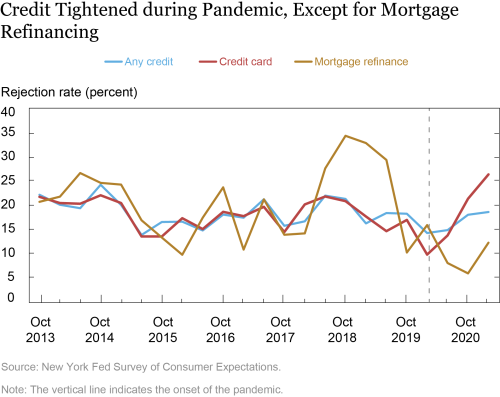

Among those who applied for any type of credit, the share reporting a rejection has increased monotonically since the onset of the pandemic, from 14.2 percent in February 2020 to 18.5 percent in February 2021. As shown in the next chart, the increase was relatively modest and within the range of changes observed in our series’ history. The rejection rate for credit card applicants shows a somewhat more noticeable increase, rising from a series low of 9.7 percent in February 2020 to a series high of 26.3 percent a year later—a 170 percent increase. Rejections of requests for credit limit increases (not shown) follow the same trajectory—reaching a new high of 40.3 percent in February 2021. The reported rejection rates for auto loan and mortgage applicants (not shown) follow less of a clear pattern over the past year.

Rejections reported by mortgage refinance applicants initially declined, but then rebounded somewhat in February 2021 to 12.2 percent, remaining below the 15.8 percent reading a year earlier. The steep increase in demand and some easing in available credit is consistent with the general strength of the housing market and historically high levels of home equity. These findings from our survey are largely consistent with indicators of credit demand and credit tightening reported by loan officers in the SLOOS.

When distinguishing respondents by age and credit score, we find that the patterns in application and rejection rates described above are largely broad-based across age and credit score groups, with two exceptions. First, the February 2021 rebound in application rates is generally much larger for respondents with self-reported credit scores between 680 and 760, aside from mortgage refinances, where the largest increase is among those with scores of 760 or higher. Second, the increase in the reported overall rejection rate during the pandemic was by far the largest for those with low credit scores (680 or below).

Two New Measures of Unmet Credit Demand

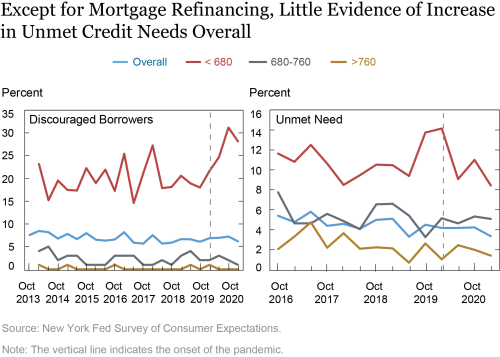

Turning now to our two alternative measures of latent credit demand (or unmet need), we first consider our backward-looking measure (shown in the left panel below). The share of discouraged borrowers, which we define as respondents who reported not applying for a loan (despite having a need for it) because they expected their application to be rejected, initially remained stable at 6.9 percent from February to June of 2020, rose slightly to 7.2 percent in October, and then fell to 6.1 percent in February 2021. Interestingly, this overall pattern masks a decline in borrower discouragement among those aged 40 and under and 60 and over, with the rate for the middle-age group increasing somewhat from 6.1 percent in February 2020 to 9.1 percent a year later. Similarly, we see an increase in discouraged borrowing among those with credit scores of 680 and below (from 21.6 percent to 28.1 percent), while seeing a slight decrease for those with higher scores.

Finally, we turn to our second alternative measure of latent credit demand, our forward-looking measure, available since October 2016. We first find that expected credit applications, both unconditional and conditional upon guaranteed acceptance, declined following the onset of the pandemic and more recently have experienced a considerable rebound. The initial decline in expected demand, even under guaranteed acceptance, substantiates our earlier finding of a general decrease in credit demand during the first eight months of the pandemic. Considering the difference between the two expected application rates—our indicator of unmet credit need—we find, as expected, that the gap is persistently positive, indicating a lower unconditional expected application rate due to a non-negative probability that the application will be rejected.

The panel on right above shows a simple unweighted average of the gap for mortgage, credit card, auto loan, credit limits, and mortgage refinance applications. After the onset of the pandemic, there is a slight decline in unmet credit need across all loan types, with the important exception of mortgage refinance applications. In contrast to our backward-looking measure of unmet credit (which does not distinguish between loan types), here for most loan types we find the decline in unmet need to be the largest for those with low credit scores (under 680). For mortgage refinancing (not shown), we see instead a slight rise among mortgagors in unmet need from 6.1 percent in February 2020 to 7.3 percent in June and 9.1 percent in October. However, by February 2021 the gap had narrowed to 5.5 percent. As was the case for the backward-looking measure, the increase in unmet need for refinancing is the largest for those with lower credit scores (below 680).

Conclusion

In this post, we used new data from the SCE Credit Access Survey to study the evolution of consumer credit demand and supply during the COVID-19 recession. We find that credit demand dropped sharply during most of 2020, especially for credit cards, with a modest rebound observed by February 2021. We also observe a modest increase in credit rejection rates during 2020, especially for credit cards. Despite this credit tightening and increased unemployment, we see no meaningful increase in discouraged borrowing and unmet credit need. Mortgage refinancing is the main exception to this general pattern, showing a steep increase in demand and some increase in unmet need, especially for those with lower credit scores.

These overall results likely evince the impact of large fiscal interventions, including stimulus checks and expanded unemployment insurance benefits, which have enabled many households to pay down debt, especially credit card debt, and increase their saving. Even among those with low credit scores, while unmet credit needs remain formidable, instead of an increase in expected unmet need we actually see a decline for the group for which unmet need is typically high. The only clear evidence of an increase in unmet credit needs is found for mortgage refinancing, where lower credit score mortgagors have been less able to take advantage of the low-rate environment.

Jessica Lu is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Wilbert van der Klaauw is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jessica Lu and Wilbert van der Klaauw, “Consumer Credit Demand, Supply, and Unmet Need during the Pandemic,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, May 20, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/05/consumer-credit-demand-supply-and-unmet-need-during-the-pandemic.html.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics