The 25 percent of low-income Americans without a checking account operate in a separate but unequal financial world. Instead of paying for things with cheap, convenient debit cards and checks, they get by with “fringe” payment providers like check cashers, money transfer, and other alternatives. Costly overdrafts rank high among reasons why households “bounce out” of the banking system and some observers have advocated capping overdraft fees to promote inclusion. Our recent paper finds unintended (if predictable) effects of overdraft fee caps. Studying a case where fee caps were selectively relaxed for some banks, we find higher fees at the unbound banks, but also increased overdraft credit supply, lower bounced check rates, and more low-income households with checking accounts. That said, we recognize that overdraft credit is expensive, sometimes more than even payday loans. In lieu of caps, we see increased overdraft credit competition and transparency as alternative paths to cheaper deposit accounts and increased inclusion.

Bouncing Out

Everyone by now understands the importance of a solid credit score, but the parallel world of debit scores is less familiar. When depositors are unable or unwilling to repay overdraft loans and fees, banks close their account and report their deposit history to a third-party debit bureau such as ChexSystems. Closing the account can stem future credit losses but not past ones; the average loss to banks per closed account is about $310 and such losses accounted for 12.6 percent of gross loan losses (FDIC 2008). A low debit score due to unpaid overdrafts follows the depositor, so they may be blocked from opening an account at another bank. As the authors of a (rare) study of account closings conclude: “…customers that bounce too many checks can find themselves bounced out of the banking system.”

Bouncing in with Fee Caps?

As a way to lower deposit costs and promote inclusion, Federal legislators recently introduced bills to limit or otherwise constrain overdraft fees: the Overdraft Protection Act of 2019 and the Stop Overdraft Profiteering Act of 2018. Although we agree that costly overdrafts drive vulnerable depositors from the banking system, economic principles suggest how a fee cap might go wrong. Overdraft coverage is credit for a fee so a fee cap amounts to a usury limit and lenders are well known to shun (“ration”) riskier borrowers under usury limits (e.g., Rigbi, 2013). Banks didn’t start offering credit cards in very large numbers, for example, until they found a loophole around state usury limits and could charge higher rates. If overdraft credit is like other credit, a fee cap would make banks be less willing to cover overdrafts and less willing to open accounts from depositors with low debit scores. Less overdraft credit and more bounced checks could, by increasing the cost of accounts to depositors, cause more not fewer unbanked households.

A Fee Cap “Experiment”

To investigate that possibility, we study a case where fee ceilings were selectively relaxed for some banks. In 2001, nationally chartered banks were effectively exempted from fee caps imposed by four states. That makes a good natural experiment because the “treatment” (the exemption) came at the Federal level, thus mitigating concerns that state conditions were driving it. It also helps that not all states had limits because we can compare outcomes at national banks versus others after the exemption in states with limits and without. Using that strategy and various data, we produce three main findings.

Higher Fees but More Credit

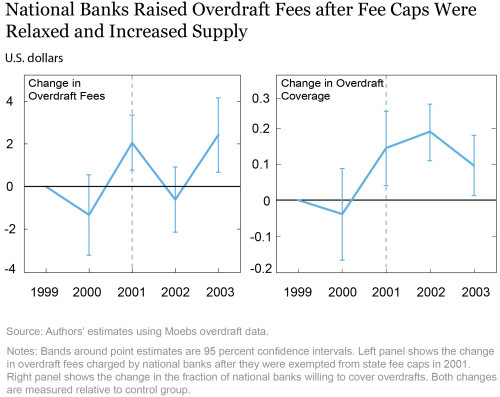

We find firstly that national banks raised fees about $2.50 (current dollars) relative to other banks after the exemption (see below, left panel). That shows fee caps do work to lower fees. However, we also find that national banks were more willing to cover overdrafts at the higher price (below, right panel). Relative to the average before the exemption, the fraction of national banks willing to cover overdrafts for a fee (rather than refusing outright) rose about 17 percent relative to the control.

Fewer Bounced Checks

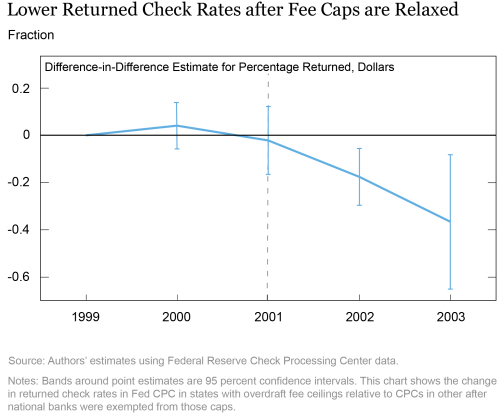

All else equal, more overdraft coverage implies fewer bounced checks (some banks call their overdraft programs “bounce protection”). We test that prediction using Fed check processing center (CPC) data. The Fed operated forty-six CPCs in 2000, with six in states that capped fees. Comparing CPCs in those states to others, we find returned check rates (per checks processed) declined about 15 percent after the exemption. That converts to about 1.7 million fewer bounced checks at those six CPCs per quarter and a substantial savings to check writers for insufficient funds (NSF) fees to merchants.

NSF fees are the twin to overdraft fees; they’re the fees charged when banks refuse to cover a check. Bank NSF and overdraft fees are about equal so the savings to depositors when banks do cover the check are on the NSF fee not owed to the merchant that accepted the check. Merchants’ NSF fees can (legally) rival banks, so avoiding two $30 NSF fees in exchange for a $30 overdraft fee saves the depositor $30, not to mention the embarrassment and stigma of bouncing a check. The benefit from bounced check protection (in the strict sense) is so clear that banks can cover checks without formal opt-in by depositors (electronic overdrafts, by contrast, require opt-in).

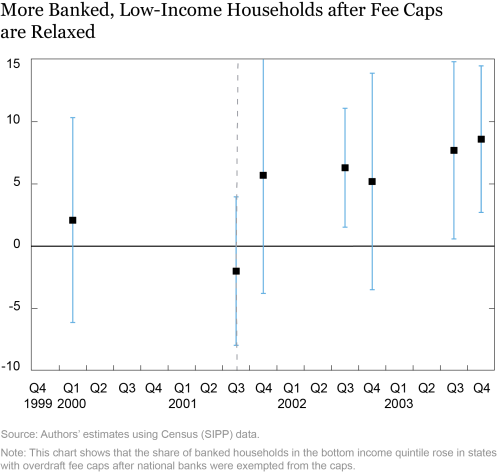

By preserving check acceptance and thus account value, bounce protection might prevent vulnerable depositors from bouncing out. Even the friendliest “local” merchant will eventually reject checks from people who bounce too many or take too long to settle. That feedback could make account ownership by lower income households unstable; if a shock causes a bunch of bad checks and reduced check acceptance, the account becomes essentially worthless. The household may close it or wait until it is closed due to unpaid NSF fees. That dynamic suggests more banked households after

the fee cap exemption.

Using Census (SIPP) data, we observe just that. We find that the share of low-income households with checking accounts increases about 11 percent relative to other states after the fee cap exemption.

Better Off Unbanked?

Behavioral economists might challenge whether households are necessarily better off banked with access to overdraft credit. If overdraft costs are “shrouded,” newly banked households might eventually bounce out again once they realize the true costs. We have two findings to the contrary. First, bounced check rates don’t bounce back after fee caps are relaxed, suggesting continued savings on NSF fees. Second, as shown above, the share of low-income households that are banked remains elevated through the sample period and we don’t find (in a separate result) that they lose accounts (bounce out) at a higher rate after the change.

Takeaways

One discussant of our paper took us to mean that high overdraft fees were good for depositors; we are not saying that. Obviously, it would be better for depositors if the same credit were available at a lower price, but fee caps evidently don’t accomplish that. Increased transparency and competition—nature’s price cap—may be a better way to bring overdraft fees in line with costs and risk. Banks are known to increase overdraft credit when forced to compete with payday lenders (Melzer and Morgan) but competition among overdraft providers is unstudied. The virtual non-existence of advertising of overdraft credit suggests that inter-bank competition is weak. Emerging financial technology firms might also strengthen the state of play, particularly if they can provide real-time balance information that enables depositors to know on the spot if a transaction will cause a negative balance, and if so, whether they want credit. Finally, our findings are notable in light of recent public declarations by a few banks that they will cease charging overdraft fees. The trade-off we identify suggests that banks operating under a hard, self-imposed fee cap may be less willing to allow overdrafts, cover checks, and accept deposits from households prone to overdrafts.

Jennifer Dlugosz is a principal economist at the Federal Reserve Board.

Brian Melzer is an associate professor at Dartmouth Tuck School of Business.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Donald P. Morgan is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Jennifer Dlugosz, and Brian Melzer, and Donald P. Morgan, “Hold the Check: Overdrafts, Fee Caps, and Financial Inclusion,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, June 30, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/06/hold-the-check-overdrafts-fee-caps-and-financial-inclusion.html.

Additional Posts in this Series

Banking the Unbanked: The Past and Future of the Free Checking Account

Credit, Income, and Inequality

Related Reading

Who Pays the Price? Overdraft Fee Ceilings and the Unbanked (Staff Report)

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics