Regulations are not written in stone. The benefits derived from them, along with the costs of compliance for affected institutions and of enforcement for regulators, are likely to evolve. When this happens, regulators may seek to modify the regulations to better suit the specific risk profiles of regulated entities. In this post, we consider the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (EGRRCPA) passed by Congress in 2018, which eased banking regulations for smaller institutions. We focus on one regulation—the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR)—and assess how its relaxation affected newly exempt banks’ assets and liabilities, and the resilience of the banking system.

Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act

In response to the financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve strengthened prudential regulation of large banks, including implementing Section 165 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which required the Fed to establish stricter prudential standards for bank holding companies (“banks”) with total consolidated assets of $50 billion or more. Later, regulators indicated that the asset size threshold might be too low, as the Dodd-Frank Act applied to smaller institutions that did not pose a threat to financial stability but still faced burdensome compliance costs. In November 2017, the Senate Banking Committee reached an agreement on a bill to increase the asset threshold for prudential regulations.

The EGRRCPA, enacted May 24, 2018, provided that, effective immediately, banks with assets less than $100 billion were not subject to Section 165. Shortly thereafter, on July 6, 2018, the Fed issued a statement saying that it would not take action to require exempt banks to comply with certain existing regulatory requirements, such as the LCR. In motivating the changes, the Fed said the exempt banks typically have stable sources of funding, simple business models, and little, if any, foreign exposures, and therefore pose less of a concern for financial stability than larger banks.

The Liquidity Coverage Ratio

The LCR, finalized in 2013, requires banks to maintain enough high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to cover their net cash outflows for thirty days during a period of stress. It originally applied to large and internationally active banks with consolidated assets of at least $50 billion. Among banks subject to the LCR, those with assets between $50 billion and $250 billion (“modified LCR banks”) were subject to a less stringent form of the LCR compared to larger banks.

Possible Bank Responses to Exemption from LCR

The LCR incentivizes banks to hold liquid assets, which can be quickly exchanged for cash in a crisis, and provides a disincentive for them to hold “runnable” liabilities, which can be easily withdrawn and thus result in greater short-term cash outflows. Consistent with this interpretation, lending by affected U.S. banks decreased, relative to unaffected banks, following the finalization of the LCR.

For banks that became exempt from the LCR, one might then expect a reverse effect—that is, these banks might lend more and borrow more using runnable liabilities. Lending could be further encouraged since the Fed also relaxed certain capital regulations, such as stress tests. However, if exempt banks were not constrained by the LCR—for example, if their LCR levels were much higher than required (as was the case for one bank)—then we might not observe large changes in their balance sheets. In addition, some analysts argued that the rule changes were too small to have meaningful effects on bank balance sheets.

For our analysis, we compare modified LCR banks that became exempt from the rule (“exempt banks”) with other modified LCR banks that did not (“non-exempt banks”). Modified banks are similar in size, allowing us to better identify tailoring effects. We consider balance sheet changes around the fourth quarter of 2017, when the agreement to tailor LCR was reached, and around the second quarter of 2018 through the third quarter of 2018, when the law passed and took effect.

As of the third quarter of 2017, there were twenty-six modified LCR banks, but we exclude seven banks that lacked data for every quarter or transitioned between the exempt and non-exempt groups during our sample period. Of the remaining nineteen banks, only four became exempt from LCR. The small number of exempt banks likely mitigates any potentially adverse effects from the regulatory changes on the banking sector, while also making it difficult to draw strong conclusions from our data.

Bank Borrowing and Lending

Did newly exempt banks increase their borrowing using runnable liabilities relative to non-exempt banks? Overnight debt is considered runnable, but for exempt banks, the amount of overnight federal funds and repo funding is less than 0.5 percent of assets. However, deposits are a large source of funding for exempt banks. Certain types of retail transaction deposits are treated more favorably in the LCR relative to other deposits. Over our sample, transaction deposits fall by a modest amount (as a share of total deposits) for exempt banks while those of non-exempt banks change little. At the same time, the share of money market deposits and other savings accounts—also generally considered stable funding in the LCR—increases moderately for exempt banks relative to non-exempt banks. Overall, exempt banks’ runnable liabilities do not appear to change much relative to non-exempt banks following tailoring.

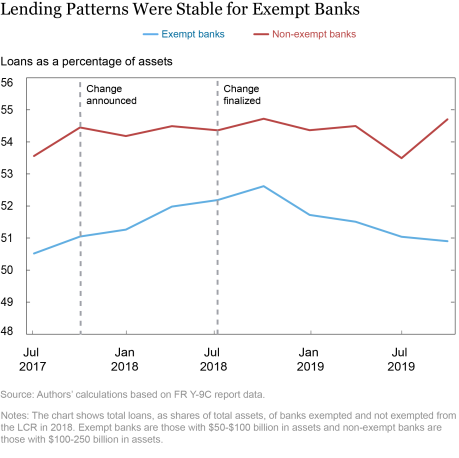

Turning to loans, the chart below shows that loans as a share of assets held by exempt banks increase by about 2 percentage points from the third quarter of 2017 to the fourth quarter of 2018 but then revert to pre-tailoring levels. The share of loans by non-exempt banks also increases by about 1 percentage point during the period, suggesting that some of the observed change in loan shares may be unrelated to the regulatory change. The stability of lending patterns also holds for specific loan types such as commercial and industrial loans and real estate loans.

To provide a summary assessment of changes in banks’ balance sheets, we examine their liquidity transformation activities (in other words, funding illiquid assets with liquid liabilities)—a key function of banks. Using a measure of liquidity creation utilizing items both on and off banks’ balance sheets, we find little change in liquidity creation by exempt or non-exempt banks following tailoring.

Bank Risk and Resilience

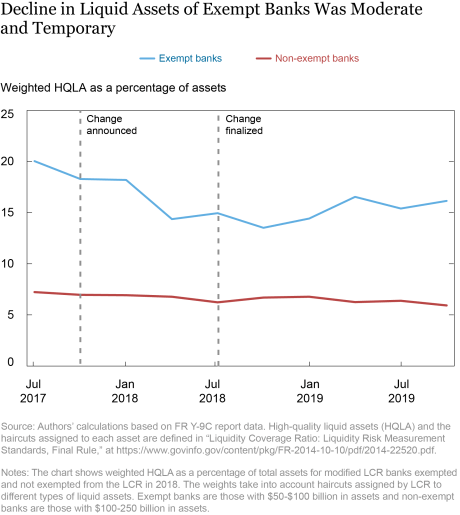

Some analysts expressed concern that exempt banks might reduce their liquid assets and that their probability of failure would thereby increase. Indeed, exempt banks’ holdings of HQLA as a share of total assets declined—relative to that of non-exempt banks—by about 5 percentage points between the third quarter of 2017 and the third quarter of 2018 but then partially bounced back, ending 2019 down by about 3 percentage points, as shown in the chart below. Thus, the decrease in HQLA appears to have been moderate and temporary.

More than individual bank risk, the LCR is designed to increase the resiliency of the banking sector. As exempt banks are smaller and less systemically important than non-exempt banks, their losses are less likely to spill over to other institutions. In this New York Fed Staff Report, the authors measure fire-sale risk, or the risk of spillover losses among banks caused by asset fire sales under hypothetical stress scenarios. Using the authors’ measure, we find little evidence that exempt banks’ contributions to fire-sale risk, as a share of their total assets, increased relative to non-exempt banks, as shown in the chart below.

Final Words

We examine a regulatory change that exempted a small number of banks from banking regulations, including the LCR, to better align the regulations to the specific risks of affected entities. Following the relaxation, we find few changes in lending and short-term borrowing of exempt banks or in the resilience of the banking sector. To be sure, analyzing the effects of regulatory changes is challenging, because few firms may be affected (as in our analysis) or because the effects may occur over several years. As bank regulations continue to evolve (for example, they were revised again in November 2019), evaluating the costs and benefits of such changes remains an ongoing task.

Rebecca Reubenstein is a senior research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Asani Sarkar is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Rebecca Reubenstein and Asani Sarkar, “Tailoring Regulations,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, July 12, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/07/tailoring-regulations.

Related Reading

Fire-Sale Spillovers and Systemic Risk

Bank Liquidity Creation, Systemic Risk, and Basel Liquidity Regulations

Did Banks Subject to LCR Reduce Liquidity Creation?

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics

Thank you for your comment. We agree that LCR may not have been the binding constraint for exempt banks. In fact, we say so in the blog “However, if exempt banks were not constrained by the LCR—for example, if their LCR levels were much higher than required (as was the case for one bank

https://investors.synchrony.com/~/media/Files/S/Synchrony-Financial-IR-V3/documents/1q2019-lcr-public-disclosure-syf.pdf

then we might not observe large changes in their balance sheets.

I think you are leaving out an important point: modified LCR may not have been the binding liquidity buffer constraint for exempt banks- Reg YY also requires ILST which may not change the reserve status for these institutions.