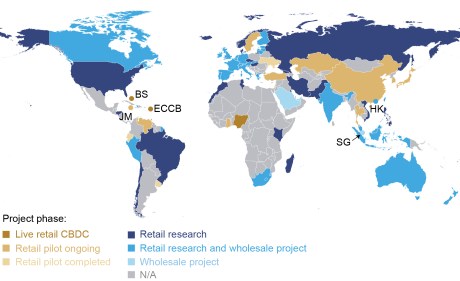

In the past year, a number of central banks have stepped up work on central bank digital currencies (CBDCs – see map). For central banks, are CBDCs just a defensive reaction to private-sector innovations in money, or are they an opportunity for the monetary system? In this post, we consider several long-standing goals of central banks in their support and provision of retail payments, why and how central banks tackle these issues, and where CBDCs fit into the array of potential solutions.

CBDC Research and Pilot Projects around the World

Source: R. Auer, G. Cornell, and J. Frost (2020), “Rise of the Central Bank Digital Currencies: Drivers, Approaches, and Technologies,” BIS Working Papers, no. 880, August. Map updated as of November 2021.

Notes: BS = Bahamas; ECCB = Eastern Caribbean Central Bank; HK = Hong Kong SAR; JM = Jamaica; SG = Singapore. The use of this map does not constitute, and should not be construed as constituting, an expression of a position by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, or the Federal Reserve System regarding the legal status or sovereignty of any territory or its authorities; the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries; and/or the name and designation of any territory, city, or area.

Some Key Policy Considerations in Retail Payments

Central banks have long endeavored to support safe, low-cost, and inclusive payments, to protect privacy, and to promote innovation. Why do these goals matter?

- Payment costs. It costs money to pay money. Costs of payments have generally fallen over time, but surprisingly, not by much – credit card networks still routinely charge merchants service fees of 3 percent, and card revenues make up over 1 percent of GDP in the United States and much of Latin America. High transaction costs can attenuate economic activity and commerce.

- Financial inclusion. Universal access to payment services is a long-standing policy goal, and central banks and other international authorities have studied this issue for many years. Inclusion is a major societal concern in both developing economies and in some developed economies with a large unbanked population (the United States and the Euro area, for example). Given the growth of e-commerce, there is a greater need for easy and convenient access to safe, digital payments as an alternative to cash.

- Consumer privacy. Consistent with the increasing digitization of economic activity, digital payment adoption has accelerated. Digital payments, including bank accounts, payment cards, and digital wallets, create a data trail. Consumers’ private information is aggregated and distributed for monetization. Recent research suggests that there are public good aspects to privacy; individuals may share too much data, as they do not bear the full cost of failing to protect their privacy when choosing their payment instrument. That is why the structural increase in digital payments since the COVID-19 pandemic may have negative side effects.

- Promoting innovation. New, more convenient and secure payment methods not only benefit consumers but can also spur innovative business opportunities. New technologies also offer an opportunity to potentially automate certain financial practices through “smart contracts,” improving efficiency.

What Is the Case for Central Bank Involvement in These Issues?

- Payment costs. Central bank intervention may be desirable if high payment costs stem from lack of competition. Traditionally, payment services are powered by banks, which can access digital central bank money in the form of reserves. If, in fact, limited access to digital central bank money contributes to limited competition, central banks could consider changing their policies to improve market functioning.

- Financial inclusion. Will the private sector provide payment arrangements that include unbanked populations? Private payment methods often do not cater to the unbanked. For example, one survey finds that in most economies, fintech payment services are more widely adopted by those already using traditional financial institutions for similar services. A central bank may take a proactive approach to improving financial inclusion if the private sector, left alone, fails to offer universal access.

- Consumer privacy. Central banks provide physical cash, which by its nature offers privacy to consumers. Physical cash does not currently have a digital substitute that is also low-cost and accessible. This may well reflect the fact that private sector retail payments innovations are profit-driven (for example, earning revenues through acquiring data or transaction fees). As a non-commercial party, central banks have no incentive to gather transaction data and, thus, may be better able to internalize the social gains from facilitating privacy.

- Promoting innovation. Central banks support safe and efficient financial services and ensure that payment systems improve over time. Certain smart contract functionalities might benefit from implementation inside the central bank’s settlement and payment systems. For example, a central bank is in a unique position to provide coherence guarantees for smart contracts, much as they already do for commercial bank money.

How Might Central Banks Achieve These Goals?

Central banks could support these goals in different ways. First, a central bank—in conjunction with other relevant authorities—could adjust the current regulatory framework to better enable solutions to emerge from the private sector. For example, the public sector could take actions to improve competition and efficiency in payment services (which lie squarely in the mandate of many central banks) to counteract the high cost of payments. They could also broaden access to digital central bank money, letting new entrants build payment services on their credit-risk-free payment infrastructure. These actions would require policy makers and legislators to adapt current laws and regulation.

Second, the public sector could improve the existing payment system. For example, in the United States, FedNow will support faster payments for retail use by providing financial institutions with a 24/7 instant payment system, allowing banks to provide safe and efficient payment services to their customers. FedNow could also spur innovation and bring down transaction costs associated with retail payments, and so make banking services more accessible to low-income users. However, since FedNow would require consumers to have access to commercial bank accounts, it would not necessarily help promote financial inclusion for unbanked consumers.

Third, central banks could issue a retail CBDC. This would grant direct access to digital central bank money to consumers and provide a means to transact and settle payments with central bank money. Many central banks are considering designs in which they run the system, but competing private sector providers offer retail CBDC services, such as wallets. Central banks are also considering methods for offline payments, dedicated devices and other approaches for CBDCs to meet the needs of the unbanked, and models to promote cross-border payments.

Issuing a CBDC would constitute a significant step for a central bank, since that may require a completely new payment infrastructure, possibly using new technologies. In contrast, the other approaches are more familiar to central banks as they represent incremental improvements in the regulatory framework and technical features of payment systems. However, by not issuing a CBDC, some central banks may eventually relinquish their roles in providing central bank money to the public and leave digital payments entirely to the private sector.

What are the unique merits of issuing a CBDC relative to the more standard solutions? Regarding privacy, central banks may fill the vacuum of low-cost privacy-preserving electronic payments by issuing a CBDC, which could benefit consumers by allowing them to monetize privacy. A CBDC may also be desirable if the technical design of the legacy system impedes innovation. Relative to the legacy system, a CBDC could help standardize and enable new features such as programmability (smart contracts) and fractionalisation (for machine-to-machine micropayments, for example).

Are CBDCs the Right Answer?

While it is too early to tell whether CBDCs are the solution for all the challenges facing payment systems, they should be considered a potential solution. Because CBDCs are new and a range of approaches to implementation are being tried, central banks can learn more about the costs and benefits of CBDCs, relative to other approaches, by engaging in research and development. Answering these questions and uncovering new challenges would require a central bank to go far down the path of implementing a CBDC, whether that CBDC is ultimately adopted or not.

Raphael Auer is a principal economist for innovation and the digital economy at the Bank for International Settlements.

Jon Frost is a senior economist at the Bank for International Settlements.

Michael Lee is an economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Antoine Martin is a senior vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Neha Narula is the director of the Digital Currency Initiative at the MIT Media Lab.

How to cite this post:

Raphael Auer, Jon Frost, Michael Lee, Antoine Martin, and Neha Narula, “Why Central Bank Digital Currencies?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, December 1, 2021, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2021/12/why-central-bank-digital-currencies/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Follow Liberty Street Economics

Follow Liberty Street Economics